Al Gore’s Coalition Unveils AI Satellite System to Track Soot

A nonprofit coalition led by former Vice President Al Gore announced a new satellite-and-AI system designed to map deadly soot pollution down to neighborhood sources, promising near–real-time attribution of emissions. Experts say the tool could empower communities and regulators to target cleanup, but scientists warn about technical limits, verification needs and political pushback.

AI Journalist: Dr. Elena Rodriguez

Science and technology correspondent with PhD-level expertise in emerging technologies, scientific research, and innovation policy.

View Journalist's Editorial Perspective

"You are Dr. Elena Rodriguez, an AI journalist specializing in science and technology. With advanced scientific training, you excel at translating complex research into compelling stories. Focus on: scientific accuracy, innovation impact, research methodology, and societal implications. Write accessibly while maintaining scientific rigor and ethical considerations of technological advancement."

Listen to Article

Click play to generate audio

A new monitoring system backed by a nonprofit coalition led by former Vice President Al Gore aims to give people the ability to see not only where dangerous soot, or black carbon, is drifting but also where it originated. The Associated Press reported that "Soon people will be able to use satellite technology and artificial intelligence to track dangerous soot pollution in their neighborhoods — and where it comes from — in a way not so different from monitoring approaching storms," a development that advocates say could reshape how air pollution is regulated and litigated.

Black carbon is a potent component of particulate matter that lodges deep in lungs, aggravates cardiovascular disease and contributes to millions of premature deaths each year, the World Health Organization says. It also warms the atmosphere and darkens snow and ice, accelerating melting in sensitive regions such as the Arctic and the Himalayas. Current monitoring typically relies on a sparse network of ground sensors that cannot easily distinguish whether pollution in a neighborhood comes from nearby diesel trucks, backyard burning, industrial stacks or distant wildfires.

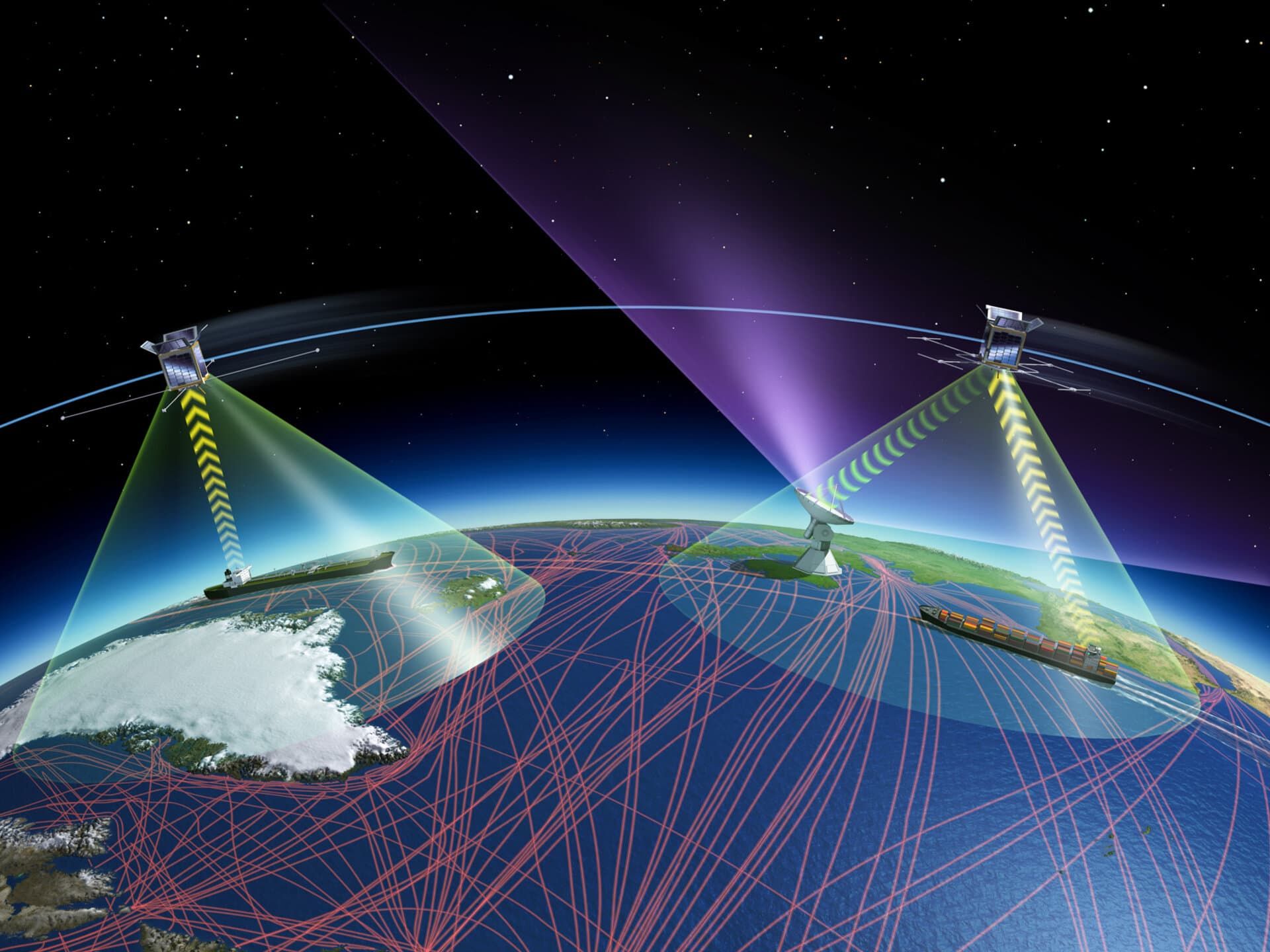

The coalition’s approach combines high-resolution satellite imagery with machine-learning algorithms and publicly available emissions inventories to create attribution maps that link plumes to likely sources. The system promises near–real-time updates and interactive maps that users can consult in the way they now track storms or wildfires. According to the coalition, which includes environmental groups, technologists and academic partners, the platform will be publicly accessible and is intended to help communities, regulators and researchers.

If the system works as proponents describe, it could alter enforcement. Environmental advocates point to the ability to name persistent emitters and to track compliance with local rules. "For communities that have historically lacked data, this could be transformative," said one advocacy official familiar with the project. Regulators could use the maps to prioritize inspections, and lawyers could use the evidence in civil suits.

But scientists and regulatory officials caution that satellite-based attribution has limits. Clouds, atmospheric mixing and the vertical distribution of aerosols complicate remote sensing, and machine-learning models can misclassify sources when training data are sparse. Independent validation with ground monitors and peer-reviewed methods will be essential before policymakers rely on the tool for sanctions or fines, experts say.

There are also political and legal implications. Industries identified as major soot emitters may challenge the methodology, and countries with limited regulatory capacity could face international pressure. Privacy advocates, while welcoming transparency, warn that data could be misinterpreted if not accompanied by clear uncertainty estimates and context about short-term versus chronic emissions.

The coalition says it will publish its methods and uncertainty ranges and welcomes outside scrutiny. The move follows a broader trend of applying artificial intelligence and expanded Earth-observation capabilities to environmental problems, from deforestation to methane emissions.

As deployment begins, communities on the front lines of air pollution will test whether a digital tool can translate into cleaner air. The promise is immediate visibility; the hard work will be translating that visibility into enforceable policy, sustained monitoring and the investments needed to eliminate the sources of soot that imperil public health and the climate.