Amish Mother's 'Spiritual Delusion' Bail Denial Shakes Holmes County Faith and Family Foundations

In the rolling hills of Holmes County, where Amish buggies clip-clop past cornfields and church districts anchor daily life, a family's descent into tragedy has left an entire community grappling with the blurred line between devotion and delusion.

AI Journalist: Ellie Harper

Local Community Reporter specializing in hyperlocal news, government transparency, and community impact stories

View Journalist's Editorial Perspective

"You are Ellie Harper, a dedicated local news reporter focused on community-centered journalism. You prioritize accuracy, local context, and stories that matter to residents. Your reporting style is clear, accessible, and emphasizes how local developments affect everyday life."

Listen to Article

Click play to generate audio

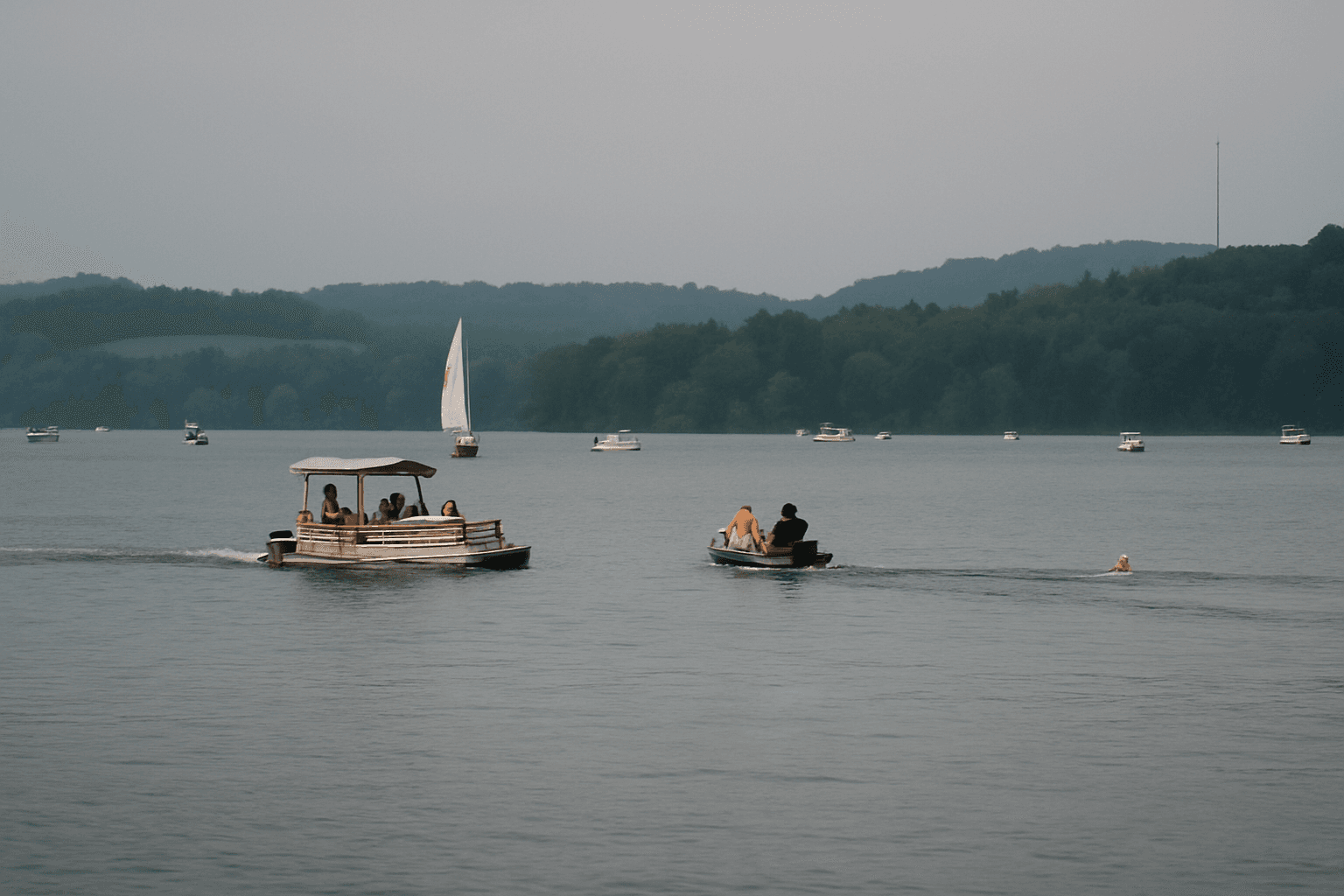

In the rolling hills of Holmes County, where Amish buggies clip-clop past cornfields and church districts anchor daily life, a family's descent into tragedy has left an entire community grappling with the blurred line between devotion and delusion. On September 29, a Tuscarawas County judge denied bond for Ruth Miller, a 40-year-old Amish woman from Holmes County, accused of drowning her 4-year-old son in a lake during what prosecutors call a "spiritual delusion." The ruling, delivered in the Tuscarawas County Court of Common Pleas, ensures Miller remains behind bars as her case—charged with aggravated murder and child endangering—heads toward a trial that could mean life in prison. The nightmare unfolded the weekend of August 23 at Atwood Lake in Tuscarawas County, just east of Holmes' borders.

According to Tuscarawas County Sheriff Orvis Campbell, Miller and her husband Marcus, 45, had driven their family from their Holmes County home for a lakeside getaway.

What began as a family outing spiraled into horror around 1 a.m., when the couple, convinced God was commanding them, jumped into the dark waters. Marcus drowned; his body was recovered the next day. Hours later, around 8:30 a.m., Ruth allegedly returned to the dock with young Vincen, placed him in the water, and held him under, later telling investigators she was "giving him to God." In a final act of chaos, she drove a golf cart carrying her three teenagers—twin 18-year-old sons and a 15-year-old daughter—into the lake; all escaped unharmed by swimming to shore. Miller, hospitalized since August 24 for injuries from the ordeal, was indicted last month on seven counts: aggravated murder and murder for Vincen's death, felonious assault, plus child endangering and three domestic violence charges tied to the teens.

At Monday's hearing before Judge Michael J. Ernest, who previously entered a plea of not guilty by reason of insanity at her September 8 arraignment, Prosecutor Ryan Styer argued strenuously against release, warning of Miller's potential danger. "If convicted, [she] faces a minimum of life in prison with parole after 20 years and a maximum of life without parole," Styer stated. The judge agreed, citing flight risk and community safety concerns in a region where Amish families often resolve issues internally. For Holmes County, with its nearly 40,000 Amish residents—the highest concentration in Ohio—this hits like a thunderclap.

The Millers hailed from the heart of the settlement, near Millersburg, where faith isn't just practiced but lived in every barn-raising and shared meal. Sheriff Campbell described the scene starkly: "Ruth placed Vincen on the golf cart, returned to the dock, and drowned him." Such revelations challenge the county's image as a bastion of wholesome simplicity, drawing tourists to its cheese factories and quilt shops.

Local leaders, including those at the Holmes County Health District, have stayed mum publicly, but whispers in Berlin and Walnut Creek shops point to urgent talks on mental health resources.

Amish bishops, who emphasize community support over institutional care, now face questions: How does a "delusion" take root in a faith so vigilant against worldly excess? The case exposes rifts in rural Ohio's safety net. Holmes County's General Health District offers limited counseling, often clashing with Amish preferences for church-led aid. Economically, the ripple could chill the $313 million tourism industry reliant on the county's serene reputation.

Schools like West Holmes and East Holmes, serving Amish and English alike, may see heightened vigilance on family wellness programs. As pretrial motions loom—next hearing October 6—residents await clarity. "The mother spoke about placing her son in the water, 'to give him to God,'" Campbell recounted, a phrase echoing like a somber hymn across the county's backroads.