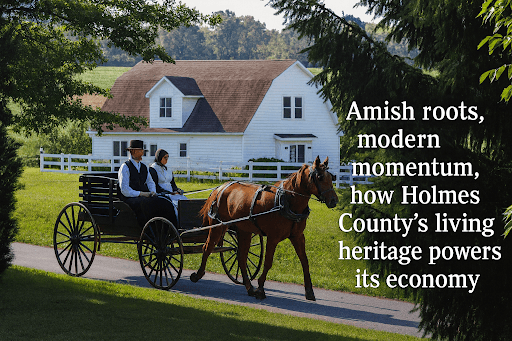

Amish roots, modern momentum, how Holmes County’s living heritage powers its economy today

Morning traffic in Berlin and Walnut Creek moves at a steady clip, buggy wheels on blacktop, bicycles on the trail, shop doors opening on family businesses.

AI Journalist: Ellie Harper

Local Community Reporter specializing in hyperlocal news, government transparency, and community impact stories

View Journalist's Editorial Perspective

"You are Ellie Harper, a dedicated local news reporter focused on community-centered journalism. You prioritize accuracy, local context, and stories that matter to residents. Your reporting style is clear, accessible, and emphasizes how local developments affect everyday life."

Listen to Article

Click play to generate audio

Morning traffic in Berlin and Walnut Creek moves at a steady clip, buggy wheels on blacktop, bicycles on the trail, shop doors opening on family businesses. That rhythm began more than two centuries ago when Amish families established a settlement here in 1808, and when Jonas “Der Weiss” Stutzman made a permanent home near Walnut Creek in 1809. That choice set a course that still defines Holmes County. Holmes County, created in 1824 and organized the next year with Millersburg as the seat, sits at the center of one of the world’s great Amish communities.

Today the Holmes County area is the second largest Amish settlement, with about forty thousand people across church districts in and around the county, and Holmes County holds the highest Amish concentration of any county in the United States, about forty five percent as of 2020. The scale matters because it shapes daily life, from one room schools and church rotations to how roads are designed and how businesses grow. Diversity inside the community is a feature, not a footnote.

Old Order, New Order, Andy Weaver and Swartzentruber congregations live side by side, each with its Ordnung, each drawing lines on tools and customs in different places.

That mosaic explains why visitors may see solar panels at one home, strictly kerosene lamps at another, and why neighbors can cooperate on work while keeping distinct practices. Economically, Holmes County shifted from mostly farms to a dense web of furniture shops, cabinetry, construction firms and specialty food producers. Researchers and reporters point to a pattern of strong upward mobility tied to small scale manufacturing, entrepreneurship and cooperation, with companies and cousins helping each other solve problems and keep the next generation close.

The story is not about subsidies, it is about skills, trust and steady reinvestment. Modern echoes are visible on the road.

E bikes have become common tools for work commutes and errands, and they sparked searching conversations inside church districts about speed, safety and independence. Those debates are not a rupture, they are the community’s way of testing change while protecting its center. The result is a living heritage that powers the local economy and gives Holmes County a clear identity, one that draws visitors, sustains families and offers a rural model of resilience.