Army Builds Fleet of Modular Mini Refineries to Secure Minerals

The U.S. Army, working with Idaho National Laboratory and private miners, is developing compact, transportable refineries to produce niche critical minerals domestically, the service told reporters and industry contacts today. The effort aims to supply defense needs, reduce reliance on concentrated overseas processing capacity and create flexible capacity that can be scaled by adding units in crises.

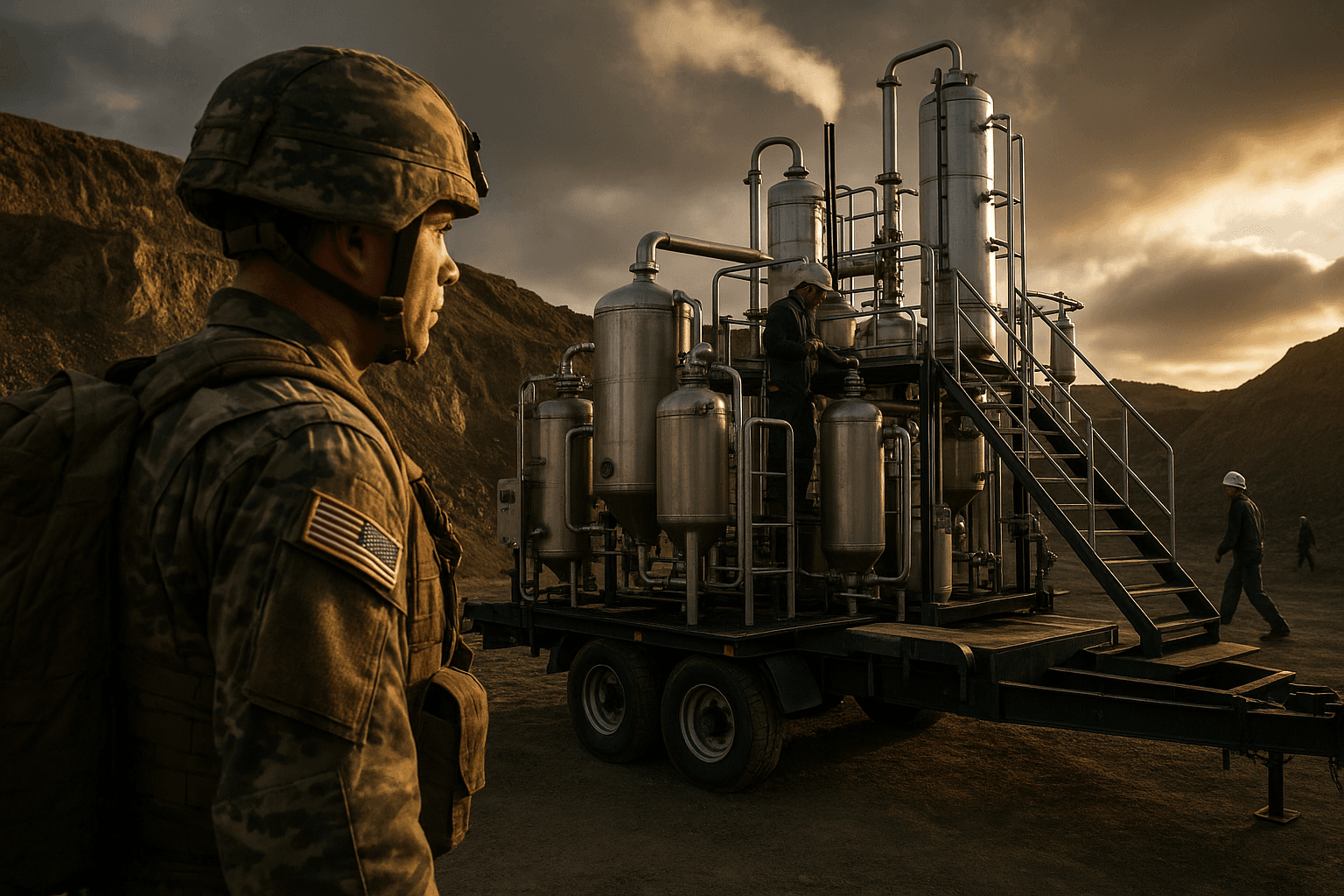

The U.S. Army is advancing a small scale industrial initiative to process strategic minerals on American soil, unveiling a compact refinery concept that can be transported in four shipping containers and produce roughly seven to ten metric tons per year of trisulfide antimony. Officials told reporters and industry contacts today that antimony is the first target for the program, which is being developed in partnership with Idaho National Laboratory and private miners and has drawn about thirty million dollars in Army funding to date.

The output level is deliberately modest relative to civilian markets, but planners say it is designed to meet specific defense requirements including components for bullets, armor and flame retardants. By creating controllable, monitored domestic processing capacity, the Army seeks to reduce the service s dependence on overseas refining networks that are heavily concentrated in a few foreign countries, particularly China.

The modular design is intended to be flexible. Individual units can be deployed to process local feedstock or to operate at secure sites, and capacity can be increased in a crisis by adding additional modules. Officials said the Army plans to negotiate with other U.S. projects for feedstock supply and that similar compact plants could later be adapted to process tungsten, rare earths and boron.

The initiative sits at the intersection of industrial policy and defense logistics. It reflects a broader push within the United States to strengthen supply chain resilience for materials designated as critical for national security. Bringing processing closer to the point of origin is meant to reduce geopolitical risk and create a chain of custody that military planners can monitor more easily than distant suppliers.

However, the concept faces practical constraints. The projected annual output is insufficient to meet civilian demand, meaning the facilities will not displace large scale commercial refineries. Sourcing consistent feedstock from U.S. mines may prove challenging, particularly for minerals whose extraction is unevenly distributed across states. Environmental permitting, hazardous materials handling and local land use approvals could slow deployment, and the Army s role as an industrial operator raises questions about long term governance, cost sharing and coordination with civilian regulators.

The project also carries political implications. Efforts to onshore processing capacity have drawn bipartisan attention in Washington because of the strategic importance of critical minerals. Lawmakers and federal agencies have debated how to allocate public funds to private partners, how to structure incentives and how to balance defense needs with environmental and community concerns.

As the pilot moves forward, key questions will include how the Army measures success, how quickly additional modules could be brought online if global disruptions occur, and how the program coordinates with broader federal efforts to build domestic mineral supply chains. For communities near potential sites, the Army s announcement opens new opportunities and potentially thorny debates about permits, jobs and environmental oversight. The coming months will reveal whether small scale modular processing can become a resilient component of the United States approach to critical minerals.