Boeing says government equity plan does not target major defense contractors

Boeing's defense chief told a national security forum that President Trump’s proposal to take equity stakes in strategic industries is intended for smaller suppliers, not the big legacy defense companies. The clarification reduces near term uncertainty for large contractors, while signaling that government investment will focus on shoring up fragile parts of the defense supply chain.

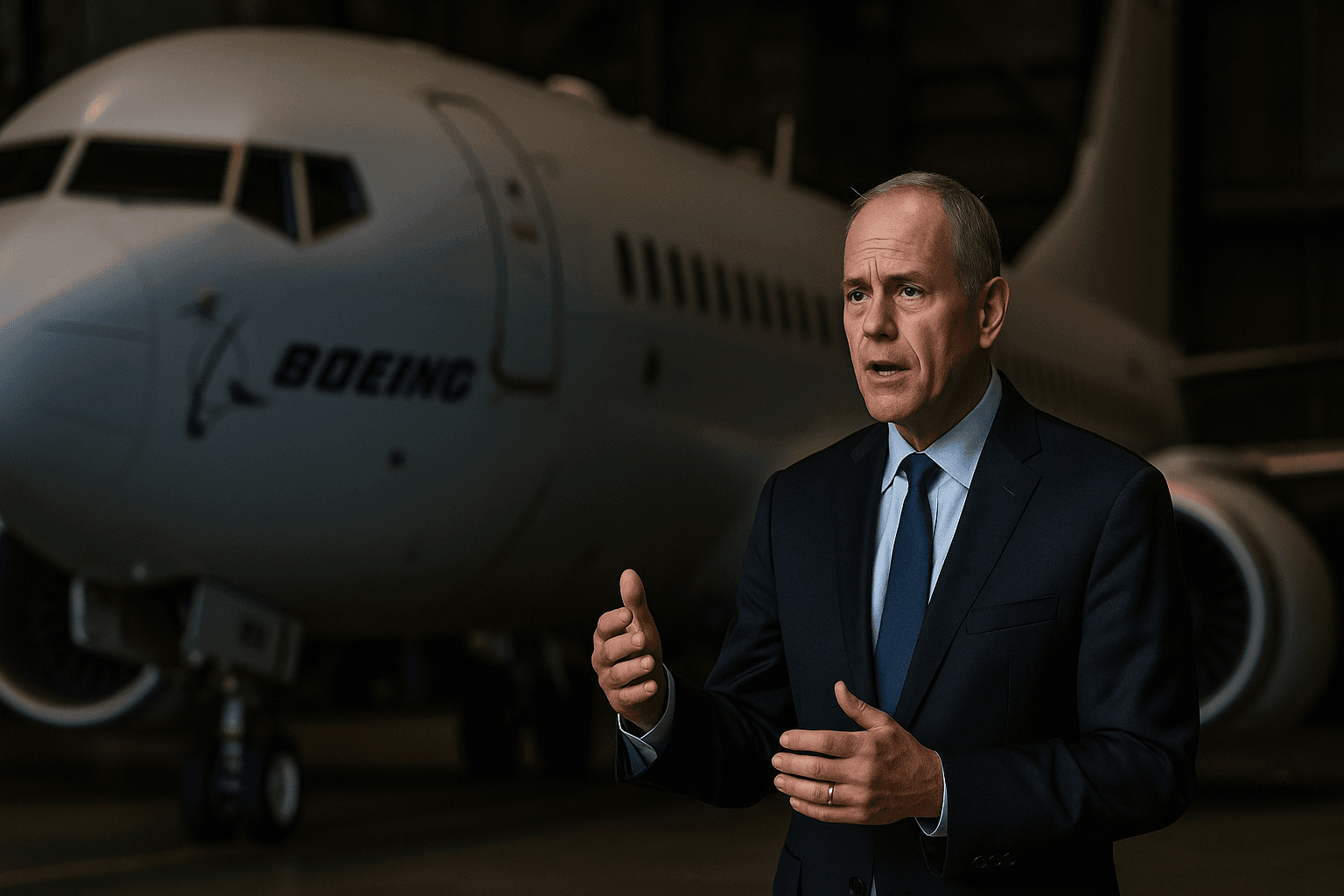

At the Reagan National Defense Forum in Simi Valley, California on December 6, Boeing Defense, Space and Security chief executive Steve Parker sought to draw a clear line between the administration’s emerging industrial policy and the established defense primes. Parker said the plan to take government equity stakes in strategic industries was aimed at smaller companies in the defense supply chain that might need investment to grow or survive. "I don’t think it really applies to the Primes," Parker said, referring to Boeing, Lockheed Martin, RTX and Northrop Grumman. He added that large contractors are expected to make necessary facility investments themselves.

Parker’s remarks contrasted with earlier comments from a senior U.S. government official that suggested stakes in larger companies were under consideration. That uncertainty had raised questions among investors and defense executives about the potential for broader government ownership to shape corporate strategy, procurement priorities and capital allocation. The administration had already taken stakes in strategic firms this year in the semiconductor and rare earth sectors, moves intended to secure supply chains deemed critical for national security.

The clarification is likely to be welcomed by the largest contractors, which collectively account for a substantial share of Pentagon procurement and possess extensive manufacturing footprints and global supply chains. For those firms, the prospect of government minority ownership would have introduced new governance complexities and potential constraints on commercial activity. By limiting the announced approach to smaller suppliers, the administration appears to be adopting a targeted intervention strategy aimed at bottlenecks rather than broad nationalization of key contractors.

Economic and market implications will center on who is viewed as eligible for government support. Small and mid sized suppliers to the defense sector often face thin margins and heavy capital intensity when modernizing production lines. Government equity injections could preserve firms critical to missile systems, avionics and advanced materials, while also creating selective winners among suppliers. Such a policy can help reduce the risk of supply disruptions, but it also raises questions about competition, state influence and the conditions attached to funding.

Policy analysts have noted a longer term shift toward active industrial policy in Washington, driven by concerns about technological competition with China, fragile global supply chains and the strategic importance of advanced manufacturing. Taking stakes in selected firms is a stronger tool than grants or loans because it gives the government an ownership role, but it also carries political and economic trade offs in terms of taxpayer exposure and regulatory scrutiny.

For now the largest defense firms will likely emphasize continued private investment in facilities and modernization, consistent with Parker’s remarks. Attention will instead turn to the suppliers in the lower tiers, where the combination of high demand from the Pentagon and fragile economics makes government capital more likely to be deployed. Observers will watch any forthcoming administration guidance for details on eligibility criteria, investment size and governance conditions.