Checkerboard Land in Ramah Challenges McKinley County Governance

Ramah Chapter’s heavily checkerboarded land and separate reservation status trace back to 19th century railroad grants and federal homesteading, creating persistent jurisdictional gaps that affect services, land use and local governance. For McKinley County residents, the patchwork of tribal trust, private and state land complicates emergency response, infrastructure planning and economic development across the Zuni Mountains foothills.

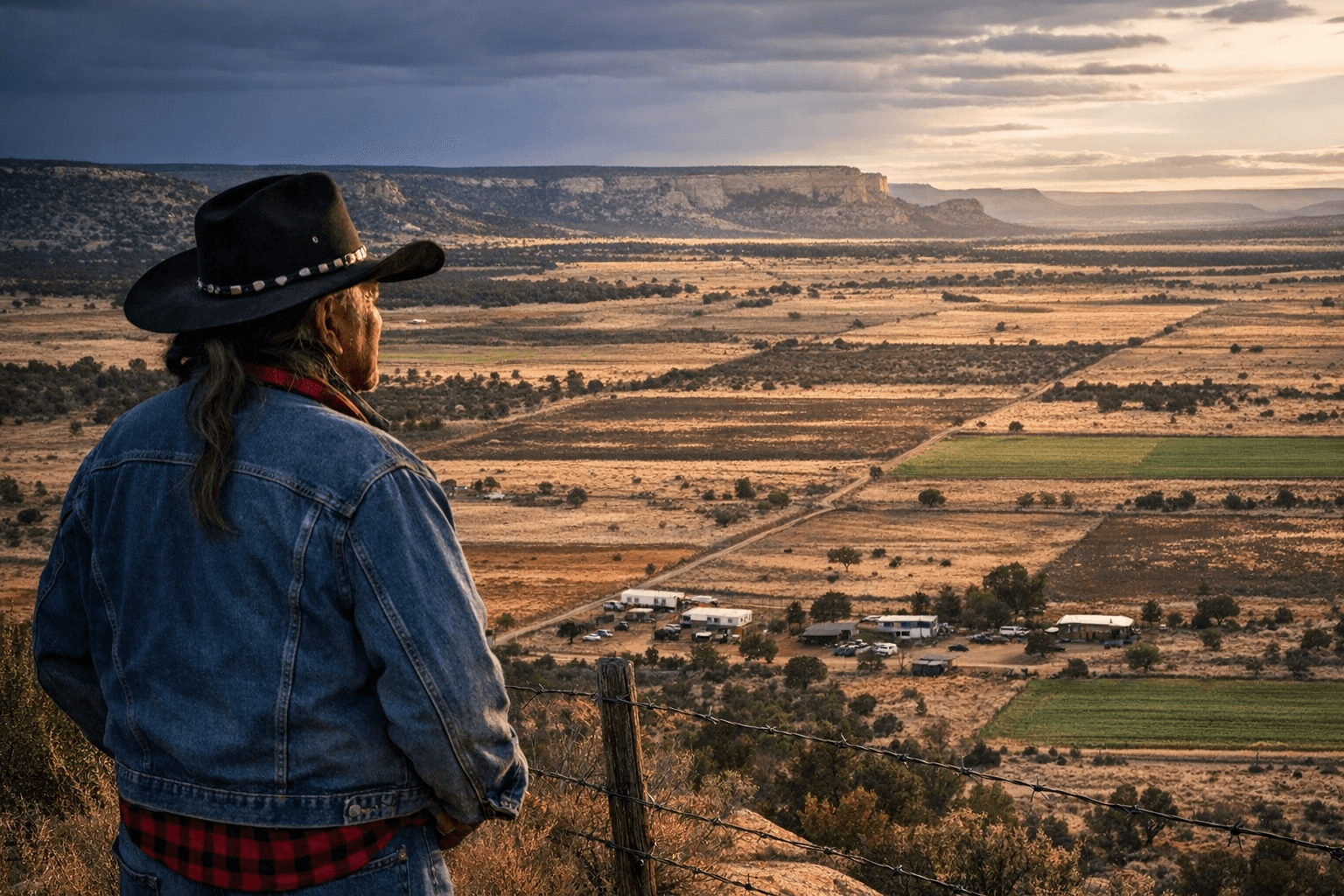

Ramah Navajo, a compact community in the foothills of the Zuni Mountains, sits on 168,000 heavily checkerboarded acres where less than half of the land is tribal trust. That patchwork arose from 19th century land grants and the Homestead Act of 1862, when parcels passed into private hands as Anglo settlement expanded. The result is a reservation that is administratively separate from the larger Navajo Nation, with its own Bureau of Indian Affairs agency and recognition as a distinct band.

Local elders have documented a longstanding local memory of those shifts. Chimeco Eriacho, 77, recalls that federal authorities did not notify Navajos they could apply for homesteads. "The government never told us Navajos we could apply for those lands," Eriacho said, framing how early policy decisions produced today’s fragmented map. That fragmentation continues to affect everyday life: "It's impossible to run livestock on land where every other mile, there's a different owner," Eriacho added, describing the practical limits on traditional grazing and land management that followed decades of competing claims. Nor was adaptation passive; when Navajo leaders sought to secure access to water and grazing, they used fencing strategies that changed local land use. "We were able to starve them out," Eriacho said, summing up a hard-fought local response to dispossession.

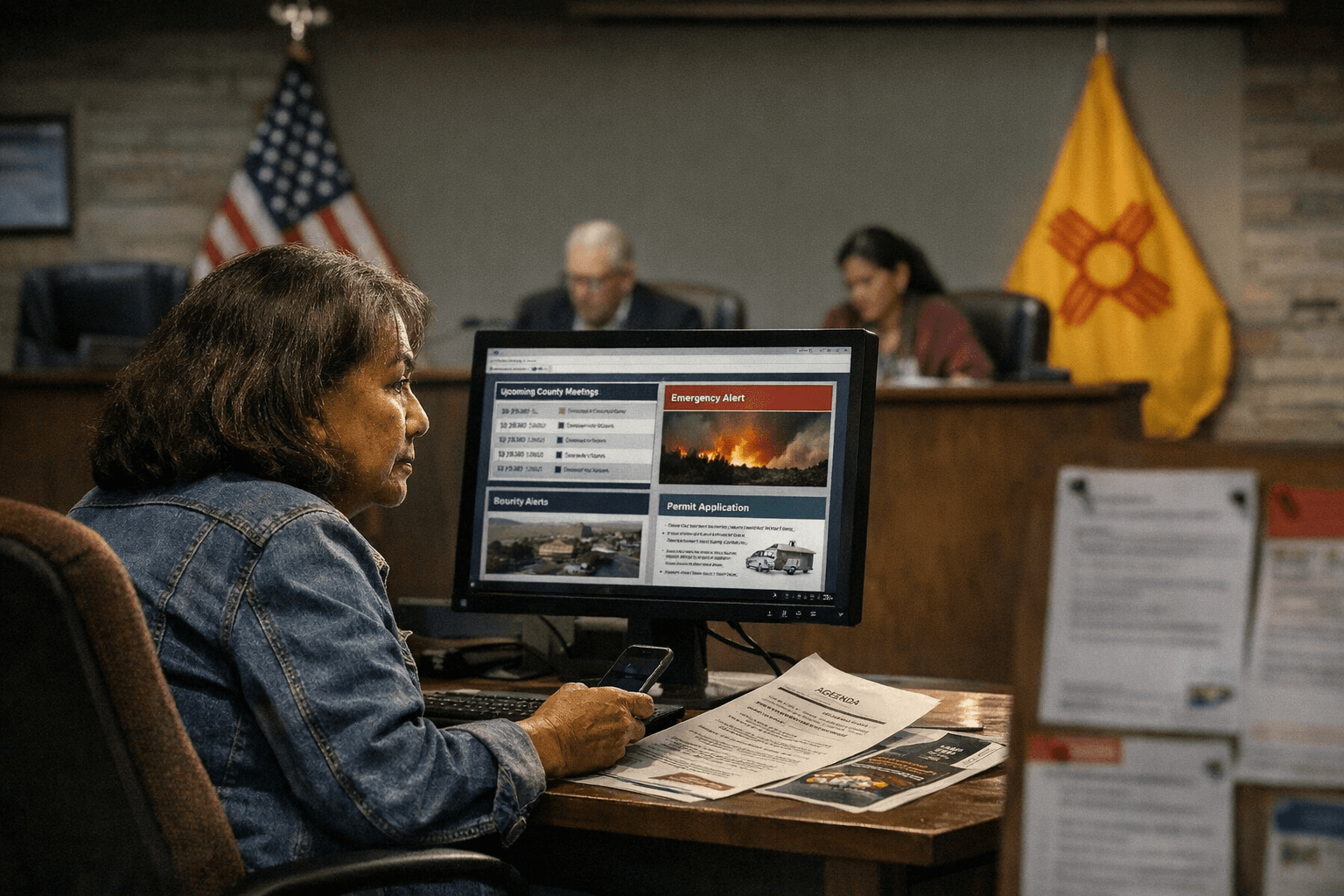

Those historical dynamics carry tangible consequences for McKinley County officials and residents. Jurisdictional confusion among tribal, federal and county authorities complicates law enforcement, road maintenance, utility service lines and emergency response across parcels that alternate between trust and private title. The structural separation of Ramah from the "Big Rez" also influences political representation and administrative coordination, requiring tailored intergovernmental agreements and on-the-ground outreach to ensure residents access county and tribal programs.

The community has long relied on self-reliance to fill service gaps. Ramah’s population was recorded at about 1,400 in the 2013 census, and local leaders and elders have worked to preserve cultural ties and local institutions in an area historically known by its Navajo name Tl'ochin', or "Onions." Land-based tourism and conservation assets such as El Morro, El Malpais and the Wild Spirit Wolf Sanctuary intersect with land ownership patterns, complicating development while offering economic opportunities if governance and access are clarified.

Policy implications for McKinley County include the need for clearer intergovernmental coordination on land use, consolidated emergency-response plans that reflect parcel-level jurisdiction, and targeted outreach to ensure residents on checkerboard tracts are included in infrastructure and voting access efforts. Addressing the legacy of railroad grants, homesteading and piecemeal ownership will require sustained partnership with Ramah leaders, federal agencies and county officials to reduce administrative friction and improve services across a landscape where history continues to shape governance.

Sources:

Know something we missed? Have a correction or additional information?

Submit a Tip