Federal Judge Orders Bond Hearings for Migrants Detained Without Review

A federal judge ruled that migrants who were living in the United States before detention under the administration's new immigration interpretation are entitled to bond hearings, finding mandatory detention without review unlawful. The decision, which certified a nationwide class, affects thousands of detainees and could reshape enforcement practices and community impacts across the country.

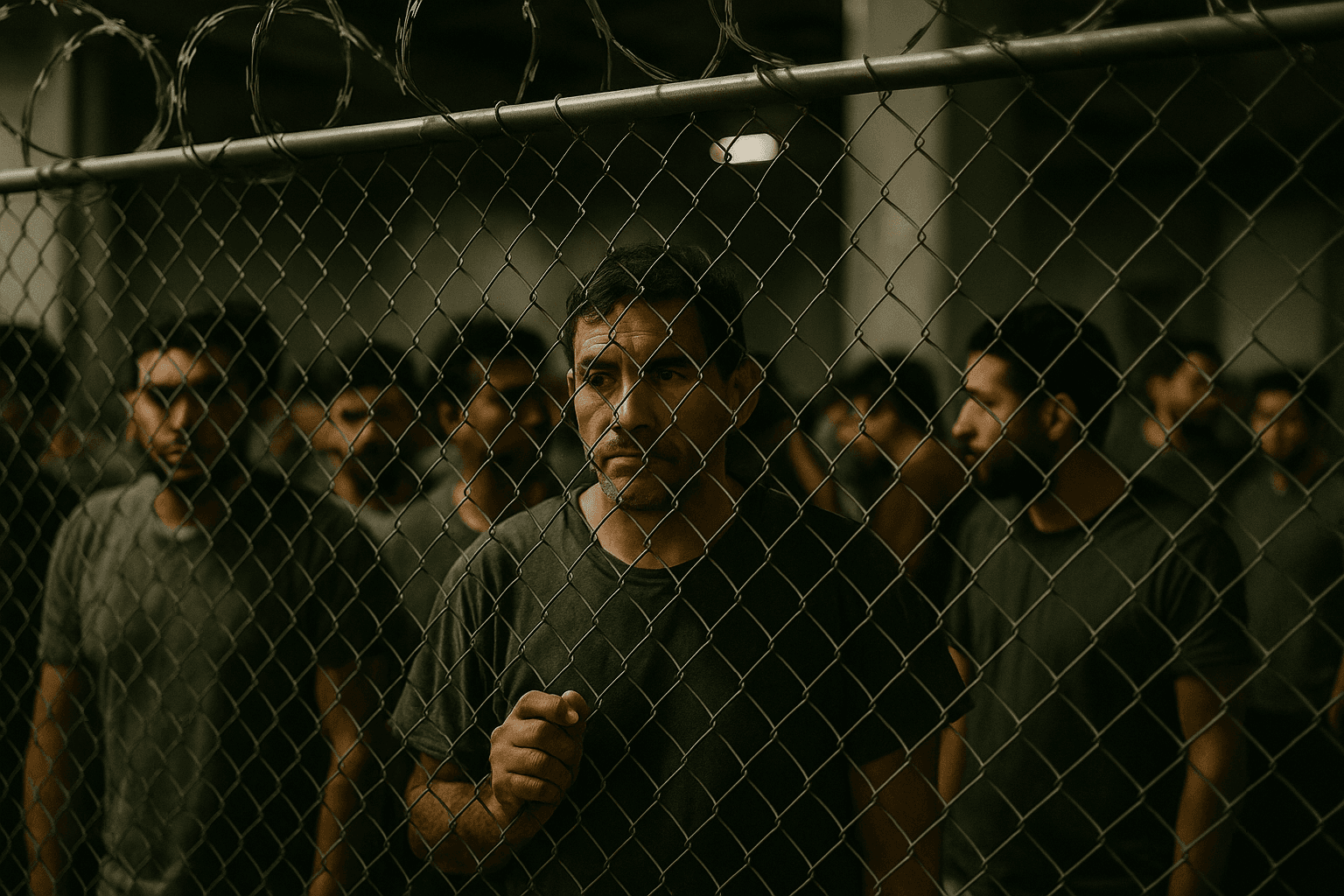

A federal judge on November 25 ruled that migrants who had been living in the United States prior to their detention under the administration's reinterpretation of immigration law must be offered bond hearings, concluding that the policy of mandatory detention without judicial review was unlawful. The ruling certified a nationwide class of affected detainees and ordered the government to provide judicial review in bond proceedings, a decision that reaches thousands of people now held in federal detention.

The dispute arose after the administration began treating some long standing residents and others who entered or reentered the country under complex circumstances as applicants for admission, a classification that agencies argued justified mandatory detention without a bond hearing. The court rejected that approach in this challenge, finding that the blanket practice deprived detainees of an opportunity for individualized consideration of flight risk and danger to the community.

By recognizing a nationwide class, the judge extended protections beyond the parties who brought the case, requiring federal authorities to offer bond hearings to similarly situated detainees across the country. The ruling has immediate human consequences. Many of the detainees have deep community ties, families, jobs, and health care needs that are interrupted by prolonged detention without timely judicial review. Legal advocates and settlement networks say that access to bond hearings can shorten detention stays and restore stability to households that have been fractured by recent enforcement actions.

Public health experts and clinicians who have worked in immigration detention warn that prolonged confinement can exacerbate chronic illnesses, contribute to mental health deterioration, and increase the risks of communicable disease spread in congregate settings. The court decision could lessen those risks by enabling earlier judicial scrutiny and potential release on bond for medically vulnerable people and others with strong ties to their communities.

The ruling also serves as a judicial check on executive interpretation of immigration statutes, pushing federal agencies to reconcile enforcement priorities with procedural protections. It raises practical questions for immigration authorities about how to implement mass bond hearings, how to identify individuals covered by the class, and how to allocate detention and legal resources. Those logistical challenges will determine how quickly the ruling translates into fewer days in detention for affected migrants.

Policy makers and community organizations are likely to view the decision through different lenses. Supporters of stricter enforcement may argue for appeals or new rules, while immigrant rights groups see the ruling as a step toward restoring due process for people who have lived in the United States for years. For communities, the ruling underscores the disproportionate burden that aggressive detention policies can place on families of color and low income neighborhoods where many detained people live and work.

The immediate next steps will be implementation of the court order and potential appellate litigation. For now, the decision offers relief to thousands of detainees and highlights broader systemic questions about how immigration law is applied, how government power should be balanced with individual liberties, and how public policy can better account for community health and social equity.