Lung Cancer Awareness Month highlights disproportionate toll on Black women

During Lung Cancer Awareness Month CBS News drew attention to persistent disparities that leave Black women more likely to be diagnosed late and to die from lung cancer. The coverage underscores gaps in screening access, treatment equity, and outreach, and points to practical steps patients and policymakers can take now.

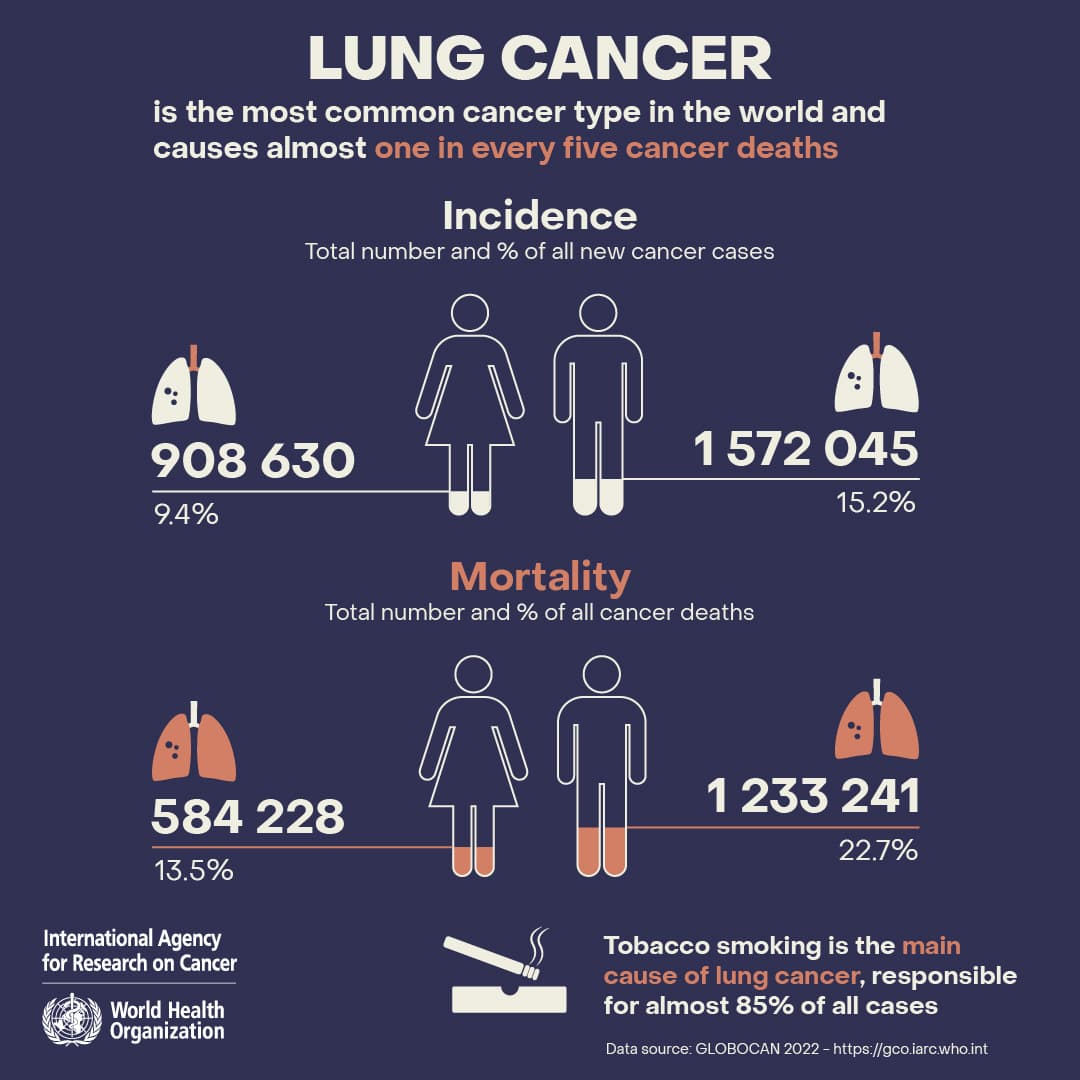

Lung Cancer Awareness Month in November put a spotlight on a troubling pattern in American health care, as CBS News underscored the disproportionate burden of lung cancer on Black women. Although lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the United States for both men and women, Black women experience higher mortality, are often diagnosed at later stages, and face barriers to screening and advanced treatments that can improve survival.

Public health experts say the problem is not biological fate alone but a web of structural forces. Black women are less likely to be referred for screening with low dose CT scans, even after the United States Preventive Services Task Force expanded eligibility in 2021 to adults aged 50 to 80 with a 20 pack year smoking history who currently smoke or who quit within the past 15 years. Insurance coverage and proximity to screening centers play a role, but research has also identified clinician bias, lack of community outreach, and logistical obstacles that include time off work and transportation.

Once diagnosed, disparities can widen. Black patients are less likely to receive timely molecular testing that can identify targeted therapies, and they are underrepresented in clinical trials that define modern standards of care. As a result, Black women may miss opportunities to benefit from precision medicines and immunotherapy that have changed lung cancer outcomes for some patients in recent years.

Environmental and social exposures also contribute. Higher rates of secondhand smoke exposure, older housing with radon risk, and greater exposure to air pollution in some communities increase lung cancer risk independent of smoking. Smoking rates alone do not explain current patterns, which is why advocates argue for broader screening strategies and for risk models that account for environmental and social determinants.

Community groups and cancer centers have begun to respond. Mobile screening vans, partnerships with faith based organizations, patient navigation programs, and culturally tailored education campaigns aim to raise awareness and reduce practical barriers. Early evidence suggests these approaches increase screening uptake in underserved neighborhoods when they are conducted in trusted community settings and when they include assistance with scheduling and transportation.

Researchers and policy makers emphasize data driven solutions. Expanding Medicaid coverage for screening and treatment, improving clinician education on eligibility and referral, mandating equitable access to molecular testing, and increasing diversity in clinical trials are among the recommended steps. Scientists also call for research into risk prediction models that go beyond smoking history to identify at risk people who would not be captured by current rules.

For individuals, experts recommend discussing lung cancer risk and the possibility of screening with primary care clinicians if they meet the current criteria for low dose CT screening. Families can test homes for radon and support smoking cessation programs. On a broader level, sustained investment in community outreach and in policies that reduce environmental exposures will be critical to closing the gap in lung cancer outcomes for Black women.