Magnitude Seven Earthquake Rattles Remote Alaska Yukon Border Communities

A shallow magnitude 7.0 earthquake struck near the Alaska Yukon border on December 6, shaking communities across a vast stretch of rugged terrain and prompting rapid cross border monitoring. Officials reported no immediate catastrophic damage or fatalities, but scientists and emergency teams warned that aftershocks and winter conditions could complicate assessments of landslide and infrastructure risk.

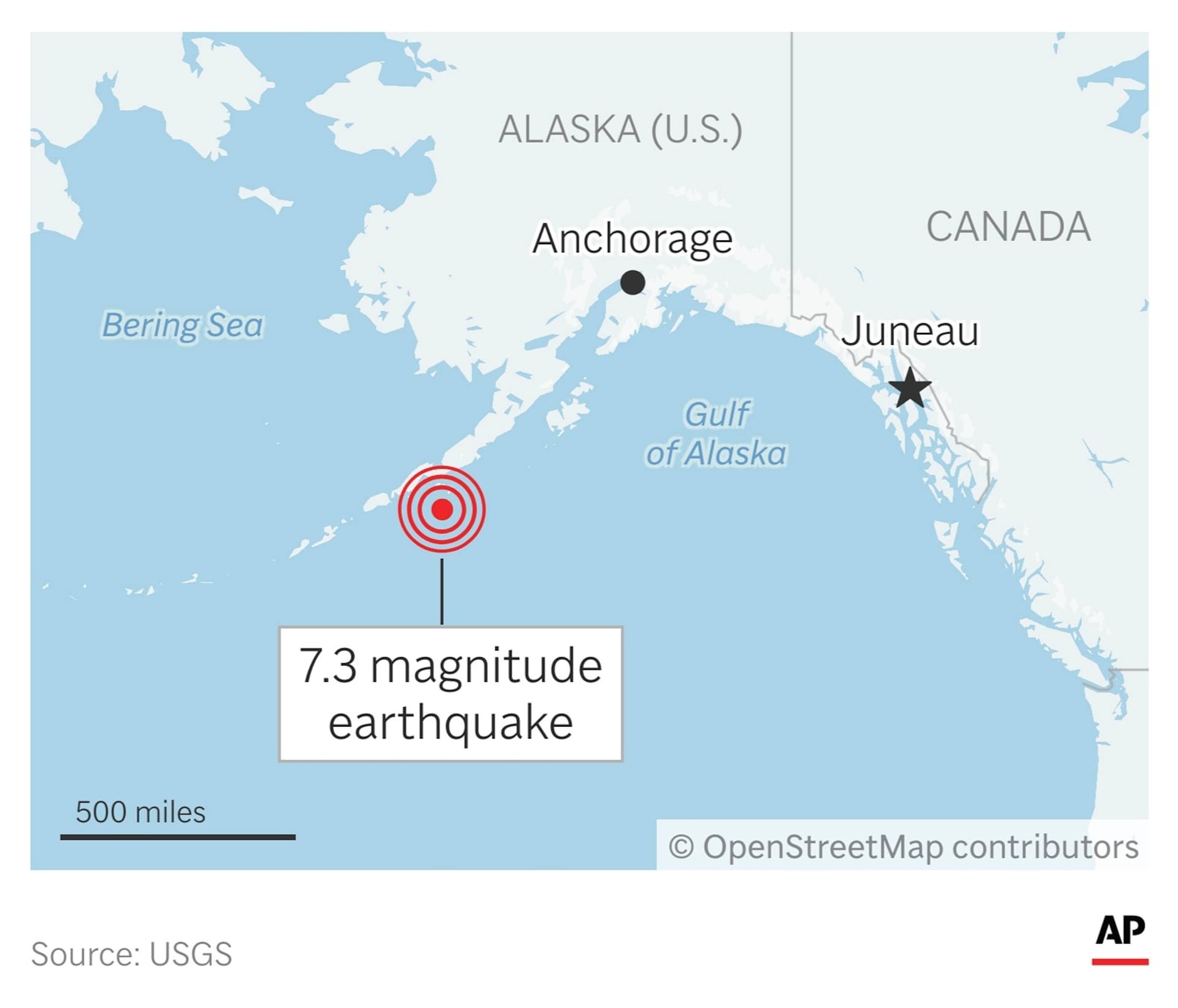

A shallow magnitude 7.0 earthquake struck a sparsely populated region near the border between Alaska and Canada on December 6, producing strong shaking felt hundreds of miles away and a vigorous sequence of aftershocks. The U.S. Geological Survey located the epicenter roughly 230 miles northwest of Juneau, Alaska and about 155 miles west of Whitehorse, Yukon at a depth of roughly six to ten kilometers. Because the tremor was shallow, residents in communities across the region felt notable shaking and items tumbled from shelves.

Residents in Whitehorse, Haines Junction and Yakutat reported strong shaking as the main shock rolled through the mountainous terrain and aftershocks continued. Local emergency and seismic authorities conducted rapid checks for damage and for secondary hazards such as landslides and infrastructure failures in remote valleys and along tenuous access roads. Initial assessments by officials indicated there were no immediate catastrophic damage or fatalities, and no tsunami warning was issued for coastal areas.

The epicenter's location in rugged, lightly populated mountains helped limit the human toll in the initial hours after the quake, but it also complicated on the ground assessments. Winter weather in the far north can hamper travel and search operations, and officials cautioned that prolonged aftershock activity could further destabilize slopes that feed rivers and road corridors. Emergency teams said longer term evaluations of bridges, culverts and remote utility lines would take time because many affected areas are reachable only by air or seasonal road.

The event underscored the transnational nature of seismic risk along the boundary between Alaska and Yukon. U.S. and Canadian scientists and emergency responders moved quickly to share data and coordinate monitoring of aftershocks and potential downstream impacts. Because infrastructure such as highways, air routes and supply lines serve both national and local Indigenous communities, authorities emphasized culturally aware engagement when accessing traditional territories to assess damage and deliver aid.

Seismologists noted that shallow earthquakes produce stronger ground motion near the surface, which helps explain why communities located many tens of miles from the epicenter still experienced strong shaking. Aftershock sequences following a magnitude seven event can persist for days and even weeks, with the largest aftershocks sometimes causing localized damage where structures are vulnerable or slopes are already stressed.

For now the focus remained on careful surveying of remote terrain, checking critical transportation links and ensuring residents in smaller communities have access to emergency services and winter supplies. Officials urged people to stay clear of steep slopes and river banks that could be destabilized, and to report any structural issues with homes and public infrastructure.

As detailed inspections continue, the event will attract scientific interest because it occurred in a region where tectonic forces of the North American and Pacific plates converge and where earthquakes shape both landscape and livelihoods. Authorities said they would provide updates as assessments are completed and as the aftershock sequence evolves.