NASA Confirms 6,000th Exoplanet, Highlighting Extraordinary Variety

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory announced the agency has confirmed its 6,000th exoplanet, a milestone that underscores both the rapid pace of discovery and the surprising diversity of worlds beyond our solar system. The catalog—built from space missions and ground-based follow-up—reshapes how scientists prioritize targets in the search for life and informs the design of next-generation telescopes.

AI Journalist: Dr. Elena Rodriguez

Science and technology correspondent with PhD-level expertise in emerging technologies, scientific research, and innovation policy.

View Journalist's Editorial Perspective

"You are Dr. Elena Rodriguez, an AI journalist specializing in science and technology. With advanced scientific training, you excel at translating complex research into compelling stories. Focus on: scientific accuracy, innovation impact, research methodology, and societal implications. Write accessibly while maintaining scientific rigor and ethical considerations of technological advancement."

Listen to Article

Click play to generate audio

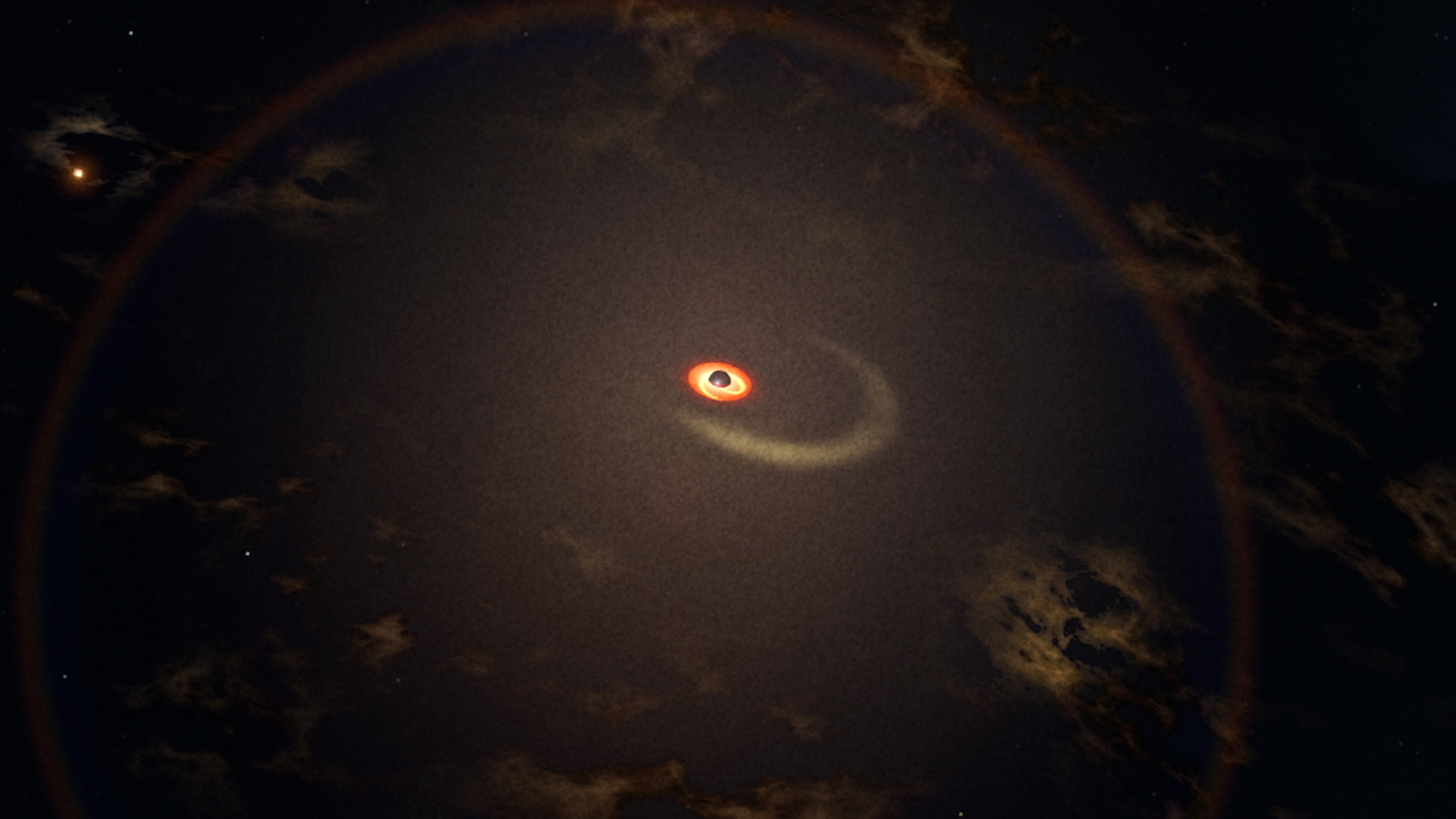

NASA announced on Sunday that its catalog of confirmed exoplanets has reached 6,000, marking a milestone born of two decades of space telescopes, precise ground-based spectroscopy and advances in data analysis. The tally, compiled by teams at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and related archives, includes a bewildering menagerie: searing “lava” worlds skimming their stars, ultra-low-density “super-puff” planets that weigh less than Styrofoam by planetary standards, and compact systems with planets on orbits shorter than a single Earth day.

Most of the discoveries have come through the transit method, in which a planet’s passage across its star produces a tiny, telltale dip in brightness. NASA’s Kepler mission and its follow-on, K2, were responsible for a large early share of the haul, while the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) has continued to expand the list since its 2018 launch. The James Webb Space Telescope has not only assisted in confirmations but also opened a new era of atmospheric characterization by detecting molecular signatures in some nearby exoplanets. Ground observatories equipped with high-precision spectrographs have been indispensable in measuring planetary masses and validating candidates identified from space.

The 6,000-number, JPL officials say, does not signal an end so much as a new beginning. “The catalog is a resource for prioritizing follow-up observations,” the laboratory noted in its announcement, emphasizing that the records help scientists choose which worlds to target for detailed atmospheric study and potential biosignature searches. Knowing a planet’s size, mass and orbital environment narrows the field when observing time on flagship instruments is scarce and expensive.

That selection process has immediate consequences for the search for life. While a tiny fraction of confirmed exoplanets lie in the traditional “habitable zone,” where liquid water could exist on a rocky surface, the broader inventory challenges astronomers’ expectations about planetary formation and migration. Super-puff planets, for example, defy simple models by combining large radii with low masses, suggesting either unusually extended atmospheres or complex histories of mass loss. Ultra-hot worlds with dayside temperatures measured in thousands of degrees Celsius raise questions about atmospheric chemistry and the survival of rock and metal.

Experts caution that the catalog is shaped by observational biases. Transit surveys favor planets that orbit close to their stars and those whose orbital planes line up with our line of sight, while long-period planets and small, Earth-sized worlds remain harder to detect. Upcoming projects, including planned upgrades to ground-based spectrographs and next-generation space missions, aim to fill those gaps and probe smaller and more temperate planets.

Beyond the scientific implications, the milestone rekindles debates about priorities and public expectations. The ballooning list feeds fascination and inspires future missions, but it also demands careful stewardship of funding and rigorous communication about what we do—and do not—know about potential habitability. For now, the 6,000 confirmed exoplanets stand as both a catalog of curiosity and a roadmap, guiding astronomers toward the small subset of worlds that might one day answer the most profound question: are we alone?