New diversion court directs people with serious mental illness to treatment

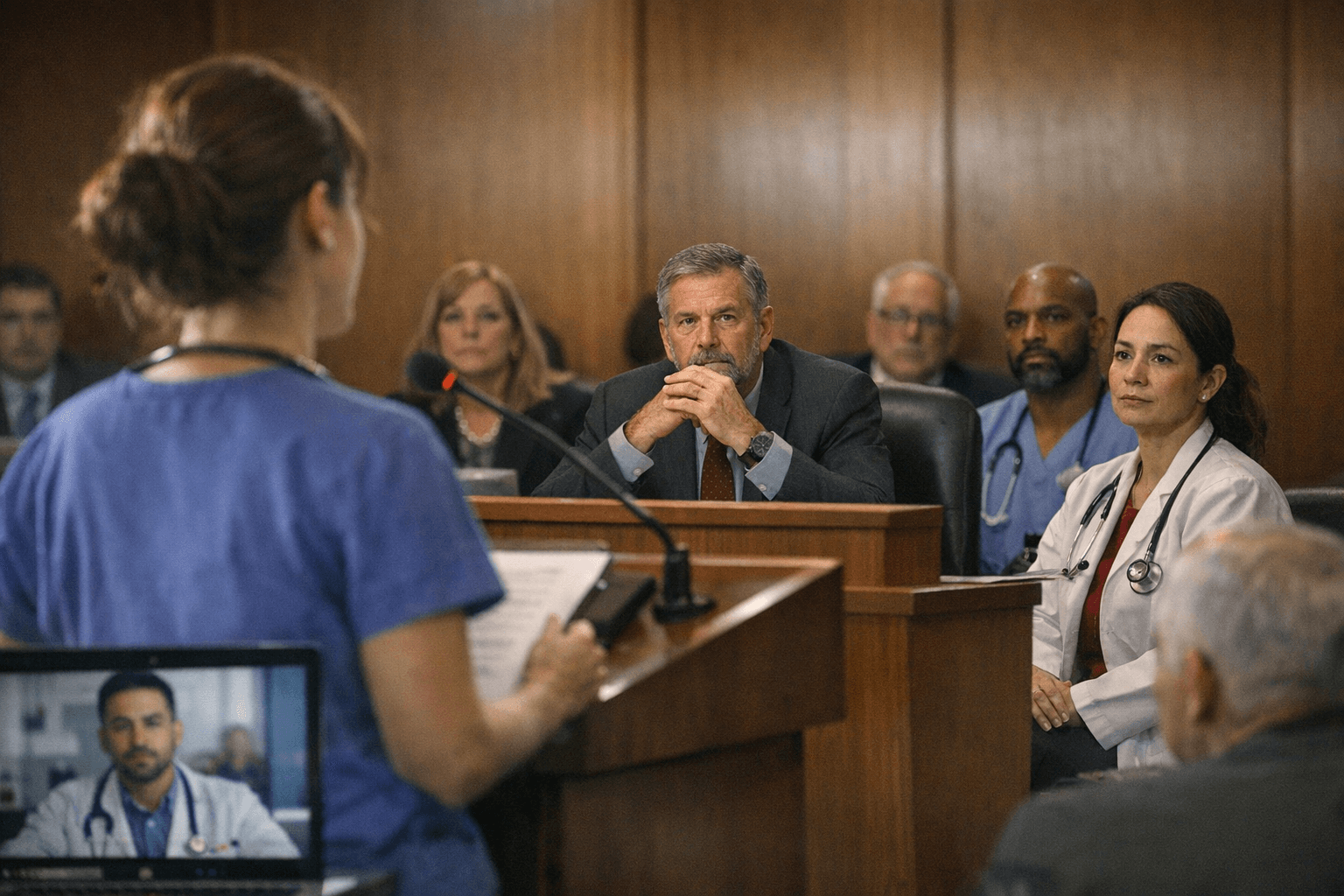

On Jan. 6, Bernalillo County Metropolitan Court launched a state-funded criminal competency diversion program to steer people with serious mental illness into treatment instead of prosecution for minor and nonviolent offenses. The program aims to reconnect defendants who previously had charges dismissed after being found incompetent to stand trial with housing, behavioral health and substance-abuse services, a shift with potential implications for neighboring communities including Sandoval County.

Bernalillo County Metropolitan Court on Jan. 6 began a new criminal competency diversion program designed to move people with serious mental illness out of the criminal justice system and into treatment. Lawmakers appropriated $293,000 per year to staff and operate the initiative, which will pay for a program coordinator, two case managers or navigators, and the behavioral health service provider A New Awakening, based in Albuquerque.

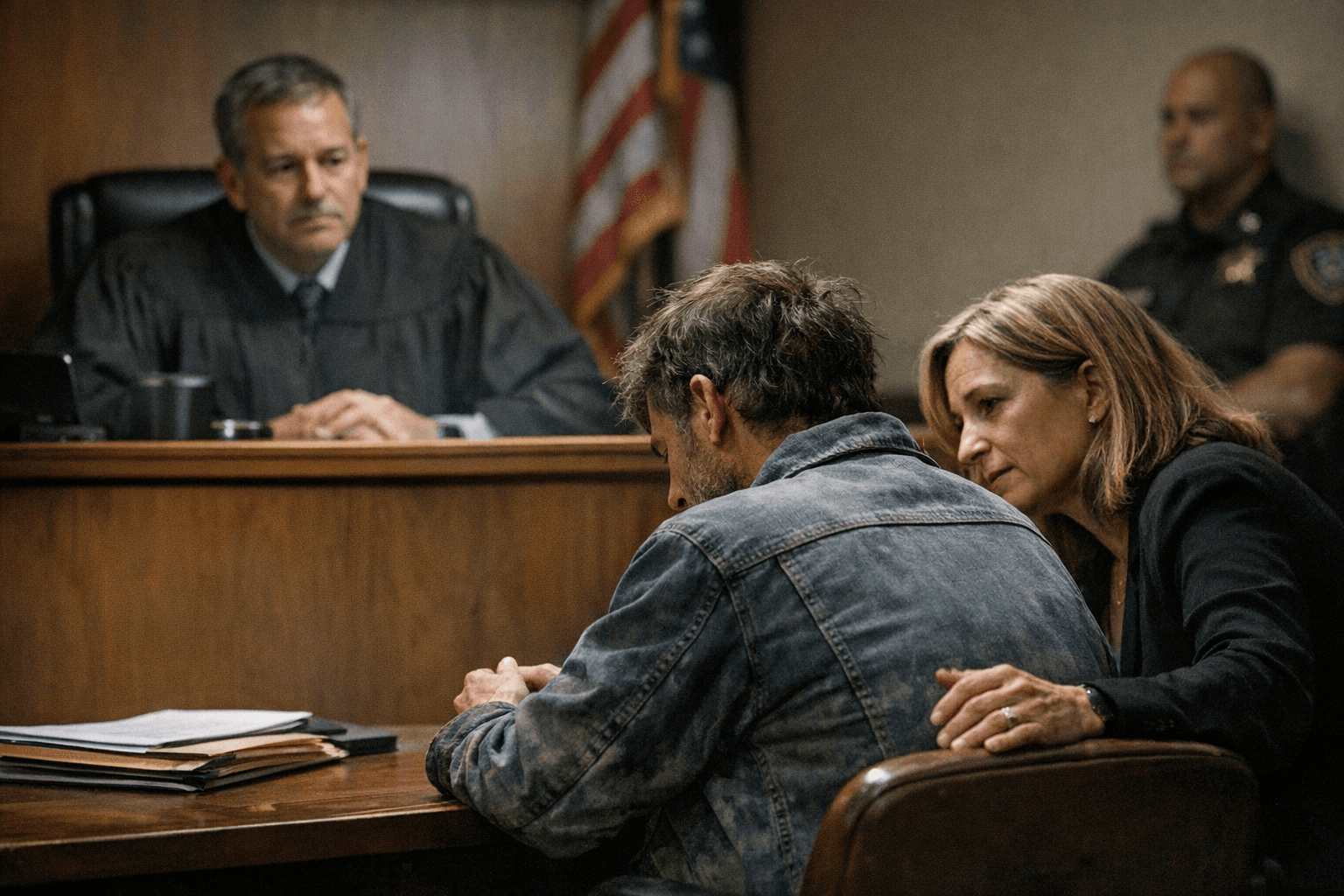

The diversion court targets people charged with misdemeanors and nonviolent felonies who previously had criminal charges dismissed because they were found incompetent to stand trial. The program excludes drunken driving charges. Rather than subjecting participants to a competency evaluation process, judges can assign them directly to trained navigators who will work to link them with mental health care, substance-abuse treatment and basic services such as housing.

State Supreme Court Justice Briana Zamora recalled that the cases she found most haunting during her years as a trial court judge involved defendants found incompetent to stand trial, and court officials framed the new program as a response to that problem. Presiding Judge Nina Safier said the court intends the program to restore services to people caught for years in the criminal justice system by reestablishing treatment connections that often lapse. Trained navigators will help clients navigate a fragmented service system and, when possible, prioritize them for limited treatment slots and housing placements.

Organizers framed the Bernalillo program as the fifth of its kind in New Mexico and the first in the state’s largest county. They recommended a modest start, enrolling no more than 30 to 45 people during the first six to 12 months. The cap reflects practical challenges: homelessness and unstable housing can complicate outreach and make it difficult for case managers to maintain contact with participants.

For Sandoval County residents, the new court offers a potential regional model for reducing repeat criminalization of mental illness and for prioritizing treatment over dismissal or incarceration when courts confront competency issues. The program represents a tangible state investment in alternatives to prosecution and signals policy interest in addressing the intersection of mental health, substance use and the criminal justice system.

At the same time, the initiative highlights systemic gaps that remain. Funding initially covers staff and a provider contract but does not eliminate longstanding shortages in housing, community treatment capacity and long waitlists that frequently leave people without stable support. Court officials say the program is focused on reconnecting people with services that have fallen away, rather than merely dismissing charges, but its success will depend on sustained funding, coordination across agencies and increased community resources to meet demand.

Sources:

Know something we missed? Have a correction or additional information?

Submit a Tip