Out-of-State Data Centers Fuel Stealthy Power Bill Hikes for McDowell Families

In McDowell County, where families already navigate tight budgets in one of West Virginia’s poorest regions, a quiet factor is inflating electricity costs: booming data centers in northern Virginia.

In McDowell County, where families already navigate tight budgets in one of West Virginia’s poorest regions, a quiet factor is inflating electricity costs: booming data centers in northern Virginia. These massive facilities, powering AI and cloud computing far from southern West Virginia’s hollers, are straining the regional power grid—and residents in Welch or Iaeger are footing part of the bill. West Virginia’s electricity rates, once among the nation’s lowest thanks to coal generation, are now climbing faster than the U.S. average.

A key reason is soaring demand from Virginia’s “Data Center Alley” in Loudoun County, home to the world’s largest concentration of data hubs.

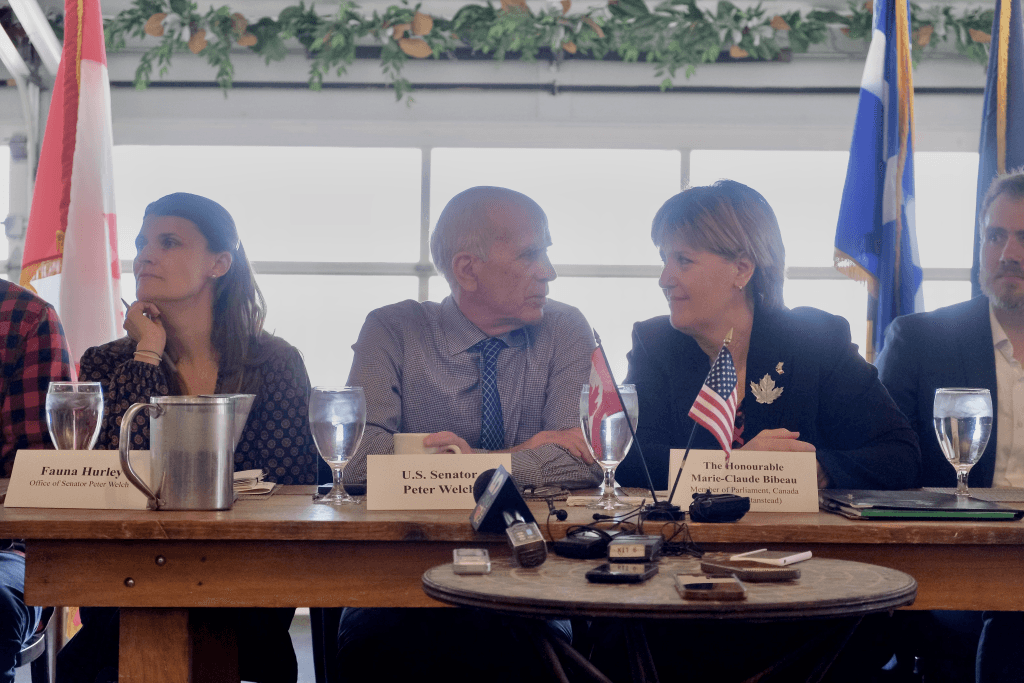

The shared PJM Interconnection grid that supplies power to both states saw capacity costs surge from $2.2 billion in 2023 to $14.7 billion in 2024, according to PJM data. These costs are distributed among all member states, including West Virginia. Proposed new transmission lines to meet Virginia’s demand could add over $440 million in costs for West Virginians over the next four decades, according to a 2024 report by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. “One of the principles of electric rate regulation is that the entity imposing cost on the system bear those costs,” said Cathy Kunkel, an energy consultant with IEEFA. “When data centers drive up system demand, that burden shouldn’t fall on low-income households hundreds of miles away.” For McDowell residents, that burden hits home.

With an 86% coal-based energy mix and a declining population, the state’s fixed costs are spread over fewer customers.

Utilities such as Appalachian Power, which serves McDowell County, may offset some auction expenses through owned generation, but residents still face higher transmission and reliability charges linked to the grid’s growing stress. The West Virginia Public Service Commission (PSC) oversees rate cases and adjustments, but consumer advocates argue the state must press for regional fairness in PJM’s allocation formulas.

Without reform, rural counties like McDowell face higher monthly bills or difficult choices about heating and lighting. While West Virginia explores attracting its own data centers for economic diversification, the benefits may take years to reach local communities. For now, residents can contact the PSC or local leaders such as the McDowell County Commission to voice concerns or seek energy assistance programs through DHHR or utility hardship funds. As the grid modernizes to support the digital age, McDowell County’s families are asking for a fair share—not just of the costs, but of the promise that new technology brings.