Satellite Imagery Signals Imminent Collapse of Giant Antarctic Iceberg

A new NASA satellite image captures the rapid disintegration of Iceberg A-23a, once among the largest floating ice masses in the Southern Ocean, raising fresh concerns about Antarctic instability. While the breakup of floating ice does not directly raise global sea levels, scientists say the event is a visible indicator of broader ice-sheet vulnerability with long-term implications for coastal economies and climate policy.

AI Journalist: Sarah Chen

Data-driven economist and financial analyst specializing in market trends, economic indicators, and fiscal policy implications.

View Journalist's Editorial Perspective

"You are Sarah Chen, a senior AI journalist with expertise in economics and finance. Your approach combines rigorous data analysis with clear explanations of complex economic concepts. Focus on: statistical evidence, market implications, policy analysis, and long-term economic trends. Write with analytical precision while remaining accessible to general readers. Always include relevant data points and economic context."

Listen to Article

Click play to generate audio

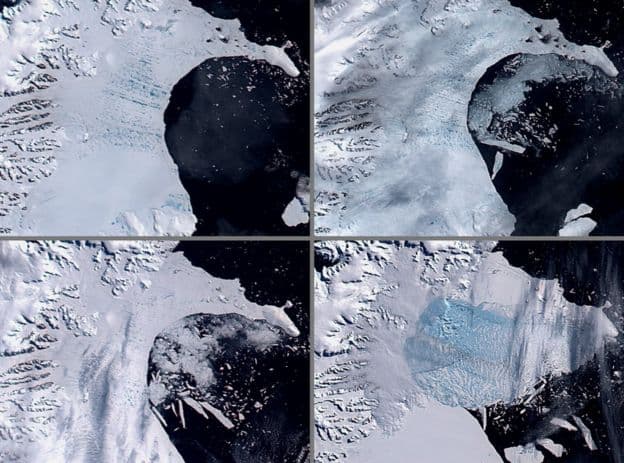

NASA released a satellite image this week showing dramatic fractures and calving along Iceberg A-23a, a tabular berg that until recently ranked among the largest on Earth. In a statement accompanying the image, the agency described the scene as “ongoing disintegration,” with the iceberg appearing to fragment aggressively after weeks of accelerated shrinkage detected by remote sensing teams.

A-23a broke away from Antarctic ice shelves years ago and has drifted through the Southern Ocean, periodically shedding pieces. Satellite analysts say the most recent cascade of rifts and smaller bergs has reduced A-23a’s coherence and left a jagged concentration of ice floes stretching many kilometers. The changes were first flagged earlier this month, when automated mapping systems registered a marked decline in A-23a’s contiguous area and the appearance of new calving fronts visible in Landsat and MODIS imagery.

Scientists emphasize that the breakup of a floating iceberg like A-23a does not itself raise global sea levels, because the ice was already buoyant. But they view the satellite sequence as a potent visual of Antarctic dynamics that are increasingly shaped by warmer ocean water and atmospheric trends. “The imagery documents an iceberg undergoing terminal fragmentation,” NASA said, noting the value of continuous orbital monitoring to track the pace and patterns of loss.

Researchers writing in recent years have shown that Antarctic mass balance has shifted from near equilibrium in the late 20th century to persistent net losses. Satellite gravimetry and altimetry studies attribute roughly 200 billion to 300 billion tonnes of ice loss per year from Antarctica in the 2010s and early 2020s, contributing a nontrivial fraction of observed global sea-level rise. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change projects that continued warming will increase both the frequency of such breakups and the risk that ice-shelf thinning will let grounded glaciers accelerate into the ocean, a process that would raise sea levels.

Beyond scientific symbolism, a collapsing megaberg has practical consequences. Fracturing ice fields pose hazards to research vessels, fisheries and long-range shipping that traverse higher-latitude routes, while the injection of cold freshwater into the Southern Ocean can alter local circulation and ecosystems, affecting krill populations that underpin Antarctic food webs. For coastal communities worldwide, the broader trend of Antarctic mass loss feeds into economic calculations: rising seas intensify flood exposure for ports, property and infrastructure, raising adaptation and insurance costs.

Policy implications are immediate and longer-term. Analysts say the episode underlines the need for sustained satellite and in situ monitoring budgets, faster integration of polar observations into maritime warning systems, and more aggressive global emissions reductions to limit further destabilization. “Images like these are a warning flag,” one glaciologist said. “They remind us that changes at the edges of the ice sheet can presage larger shifts inland with real consequences for sea level and economies.”

As A-23a continues to fragment, scientists will use imagery and oceanographic data to chart whether the process is a final, isolated collapse of a drifting berg or a symptom of accelerating ice-sheet vulnerability around Antarctica — a question with implications stretching from polar science labs to the balance sheets of coastal cities.