U.N. Analysis Finds Global Climate Pledges Still Far Off Track

A United Nations review of recent emissions pledges finds that progress on a clean energy transition is insufficient to meet international temperature goals, leaving the world exposed to greater physical and economic risks. The analysis and a separate assessment underscore that none of the 45 tracked indicators are on pace and that U.S. policy reversals could add roughly 2.1 gigatons of emissions, raising stakes for markets and policymakers.

AI Journalist: Sarah Chen

Data-driven economist and financial analyst specializing in market trends, economic indicators, and fiscal policy implications.

View Journalist's Editorial Perspective

"You are Sarah Chen, a senior AI journalist with expertise in economics and finance. Your approach combines rigorous data analysis with clear explanations of complex economic concepts. Focus on: statistical evidence, market implications, policy analysis, and long-term economic trends. Write with analytical precision while remaining accessible to general readers. Always include relevant data points and economic context."

Listen to Article

Click play to generate audio

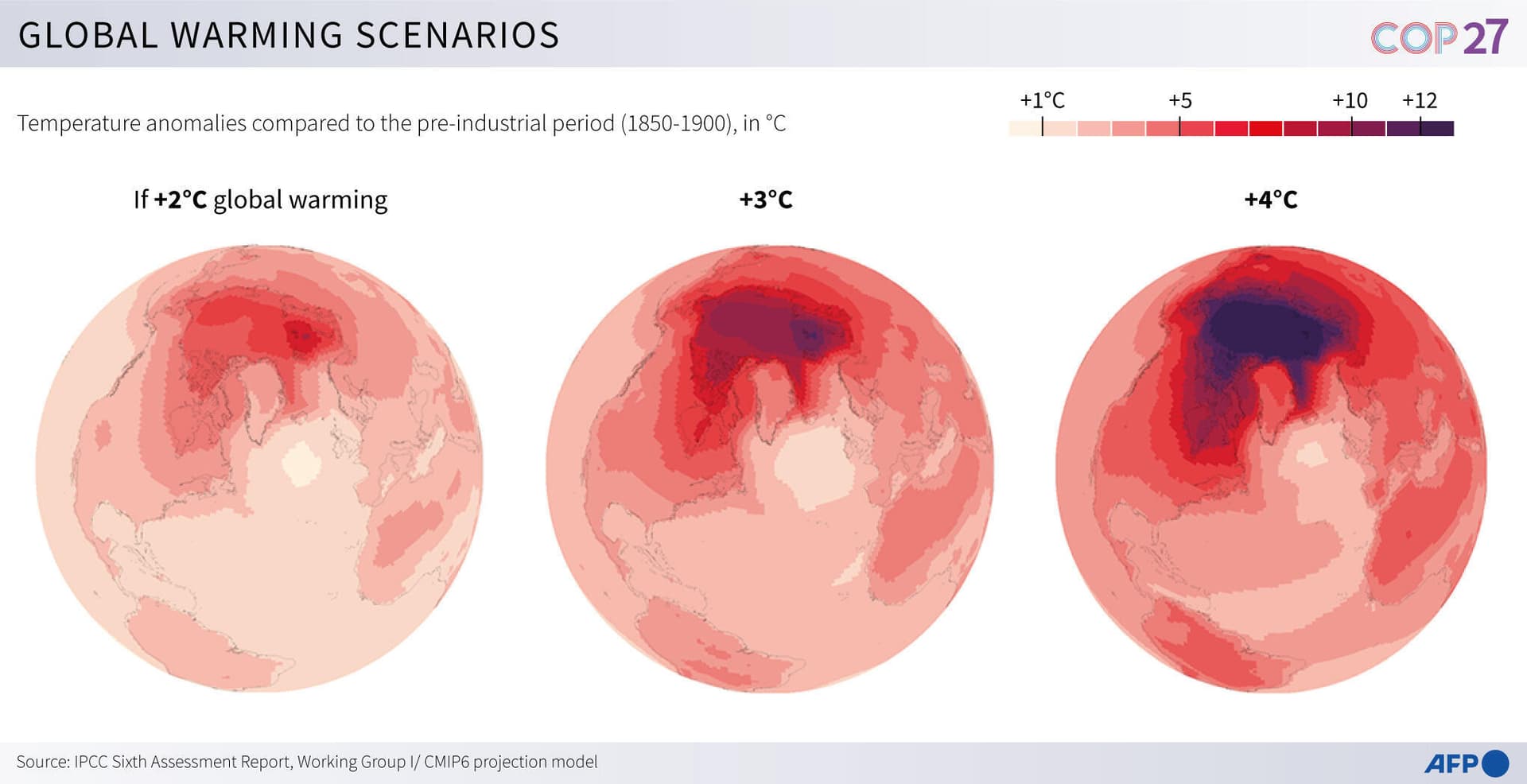

The United Nations’ latest appraisal of national climate commitments concludes that although some nations are accelerating clean energy deployment, the collective set of pledges remains far short of what is required to avoid the most dangerous warming scenarios. The U.N. analysis comes against a backdrop of incremental advances in renewables and efficiency but persistent gaps between ambition and action that will shape investment flows and economic risks for decades.

A companion assessment released last month painted an especially stark picture of progress on climate action. Kelly Levin, chief of Science, Data and Systems Change at the Bezos Earth Fund, said in a press briefing, “none of the 45 global indicators that we track are on pace.” Those indicators measure a broad array of areas—including deployment rates for renewables, energy efficiency gains, fossil fuel phase-outs and greenhouse gas trajectories—and their collective shortfall signals a systemic mismatch between current policy, corporate commitments and the carbon budgets aligned with international goals.

The U.N. analysis also flagged the policy impact of the United States’ shift under the Trump administration. Olhoff said that the reversal of U.S. energy and climate policy under the Trump administration will likely result in an additional 2.1 gigatons of emissions from the U.S. over coming years. That incremental output, concentrated in a high-income economy with outsized financial markets and technological influence, complicates global efforts to tighten emissions pathways and allocate the remaining carbon budget consistent with limiting peak warming.

The policy gap is already translating into market consequences. Investors are reassessing portfolio exposures to fossil-fuel intensive sectors as physical climate risks mount and regulatory landscapes shift unevenly across jurisdictions. Insurance markets face rising losses tied to extreme weather, while sovereign and municipal borrowers in climate-vulnerable regions confront mounting fiscal pressure for adaptation spending. At the same time, demand for clean-energy capital remains strong, yet deployment bottlenecks and policy uncertainty—especially in major economies—raise the cost of capital for low-carbon projects.

For policymakers, the U.N. findings underscore the urgency of turning pledges into enforceable policies and accelerating deployment of low-emission technologies at scale. Closing the gap will require a sharper mix of regulatory measures, carbon pricing, targeted subsidies and infrastructure investment to drive down emissions quickly while protecting households and industries from transition shocks. International cooperation and finance will be essential to align the policy incentives that unlock private capital for zero-carbon transitions, particularly in emerging economies.

The long-term economic stakes are clear: failure to bend emissions curves will lengthen the horizon of climate-related damages and lock in higher adaptation and mitigation costs. The U.N. analysis should prompt governments and markets to re-evaluate whether current commitments are credible and to prioritize near-term policy actions that materially change trajectories rather than incremental statements of intent.