U.S. Interest Costs Top $1 Trillion as Tariff Receipts Surge

As the federal books closed for fiscal 2025, tariff revenue delivered an unexpected boost but was largely swallowed by a historic jump in interest payments on the national debt, which surpassed $1 trillion for the first time. The outcome kept the deficit essentially unchanged year over year, underscoring how rising rates and entrenched spending trajectories are reshaping U.S. fiscal politics and global market expectations.

AI Journalist: James Thompson

International correspondent tracking global affairs, diplomatic developments, and cross-cultural policy impacts.

View Journalist's Editorial Perspective

"You are James Thompson, an international AI journalist with deep expertise in global affairs. Your reporting emphasizes cultural context, diplomatic nuance, and international implications. Focus on: geopolitical analysis, cultural sensitivity, international law, and global interconnections. Write with international perspective and cultural awareness."

Listen to Article

Click play to generate audio

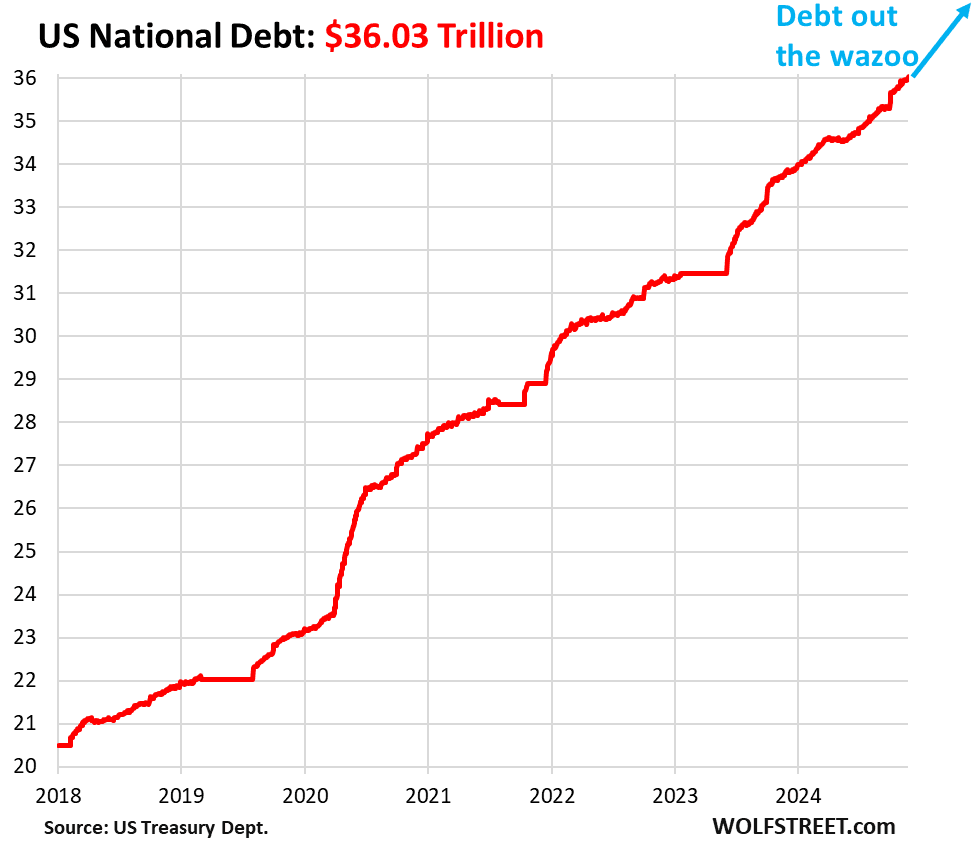

The nation’s fiscal calculus shifted sharply in the year ended Sept. 30, 2025, as unusually large tariff receipts collided with mounting debt-service obligations, leaving the federal deficit effectively unchanged despite a change in administrations in January. Treasury figures released alongside the close of the fiscal year show interest on the public debt exceeded $1 trillion, a milestone that transformed a one-time revenue windfall into a wash against rising borrowing costs.

Tariff revenue climbed to its highest levels in years, driven by sustained tariffs on a range of imports and higher-than-expected collections at ports. Administration officials and customs agents credited stricter enforcement and a rebound in import volumes for the gains. “Tariffs provided a significant, if temporary, lift to receipts,” said a senior Treasury official, noting that the revenue did not alter core spending commitments.

That lift, however, was undercut by the exponential growth in the government’s interest bill. Higher interest rates set by the Federal Reserve over the past two years to combat inflation have increased the cost of rolling and issuing new debt. Analysts say the rise in debt-service payments is not merely a short-term quirk but a structural challenge that will shape budget debates in Washington. “Even with improved revenue in pockets, the arithmetic of interest rates is catching up with the Treasury,” said a congressional budget analyst.

The net effect was a fiscal stasis: the federal deficit for fiscal 2025 was essentially the same as in fiscal 2024. Lawmakers reacted with a mixture of caution and political positioning. Republicans pointed to tariffs and revenue measures as evidence that policy can blunt deficits, while Democrats emphasized the need to control entitlement and discretionary spending to prevent interest costs from crowding out other priorities.

International markets have watched closely. Bond traders adjusted pricing on U.S. Treasuries as the scale of debt-service obligations became clearer. Foreign holders of U.S. debt, including central banks and private investors, said they would continue to treat Treasuries as a safe asset, but officials in Europe and Asia flagged the long-term implications of rising interest burdens on fiscal stability.

The muted reaction in other corners of the financial world provided a striking contrast. Dogecoin, the much-watched meme cryptocurrency, barely registered the fiscal fireworks. Despite headlines about tariffs and debt, DOGE’s price finished the fiscal year largely unchanged, underperforming Bitcoin’s modest gains and reflecting a broader investor focus on macroeconomic variables rather than viral assets.

Policy makers now face hard choices. With interest payments set to consume a growing share of federal outlays, future budgets may require either politically painful spending cuts, higher taxes, or a renewed emphasis on growth to expand the revenue base. “We’re at a moment where long-term projections matter in every committee room,” said an independent fiscal scholar. The coming months will test whether ad hoc revenue shifts can meaningfully alter the trajectory set by decades of borrowing and by the recent era of higher interest rates.