Wolf Returned to Colorado Under MOU Raises Policy Questions

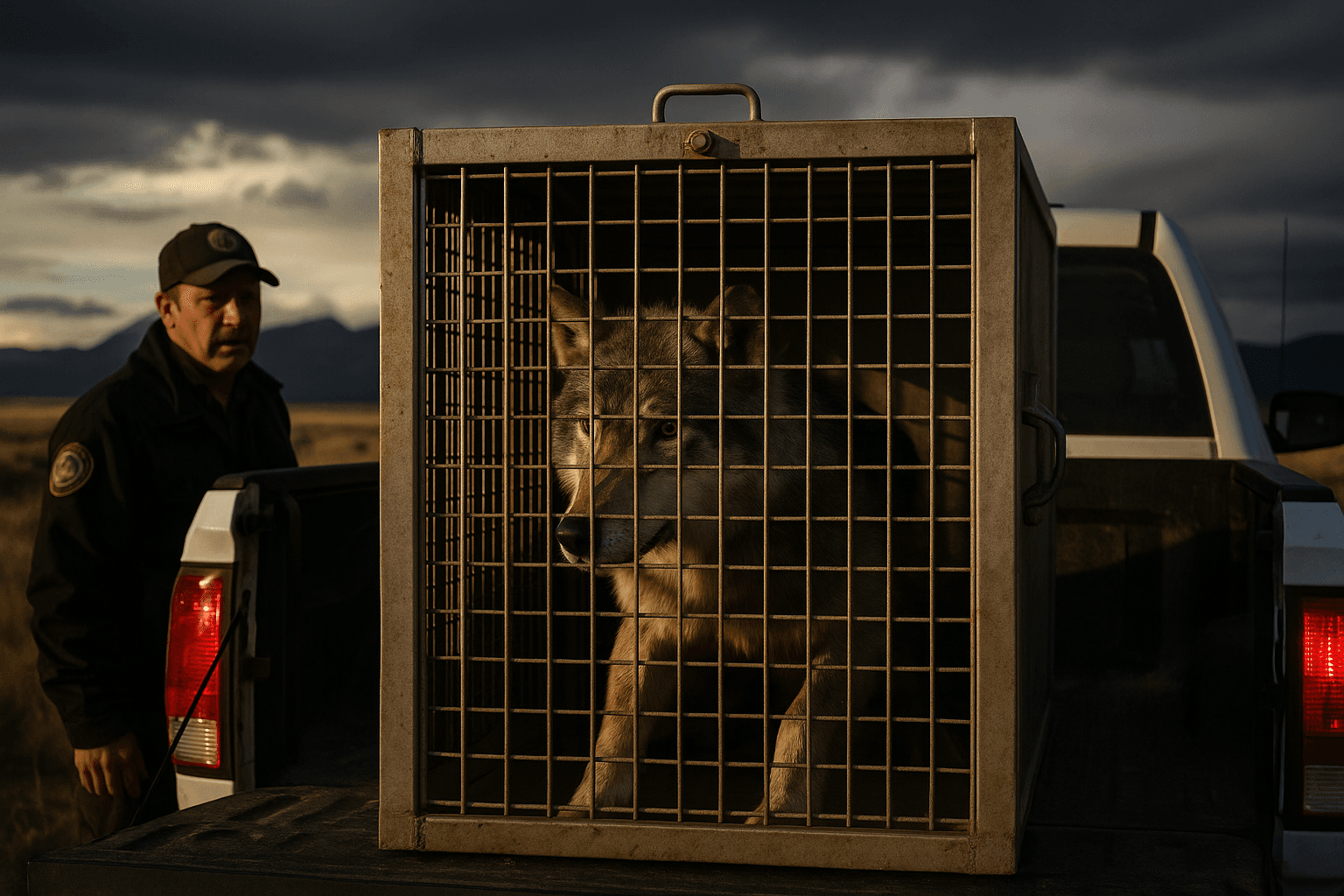

A gray wolf known as 2403 that dispersed from Colorado's Copper Creek pack was captured by New Mexico Game & Fish on December 11 and returned to Colorado under a multistate Memorandum of Understanding. The action has drawn criticism from conservation groups and scientists who say the removal undermines natural dispersal and long term genetic recovery for Mexican gray wolves, a debate with implications for local wildlife policy and community engagement.

New Mexico Game & Fish captured a gray wolf identified as 2403 on December 11 and relocated the animal back to Colorado under a multistate Memorandum of Understanding designed to keep northern gray wolves from entering New Mexico. Agencies involved relied on the agreement to justify the capture and return, while conservation groups and scientific observers protested the move as counterproductive to regional recovery goals.

Scientists and advocates contend that dispersal is a natural behavior essential to genetic exchange between populations, and that policing state boundaries for wildlife movement is not science based. They warned that repeatedly preventing northern wolves from mixing with populations to the south could impede the long term genetic resilience of Mexican gray wolves. The wolf in question came from Colorado's Copper Creek pack, a group that has previously been the subject of relocations and removals as managers balance recovery objectives with state level policies.

The case highlights institutional tensions between state wildlife agencies operating under different mandates and the broader conservation objective of restoring genetically viable wolf populations across the region. The multistate Memorandum of Understanding reflects an intergovernmental attempt to manage perceived risks, but critics say it substitutes jurisdictional preferences for landscape scale biological science.

For Los Alamos County residents the episode matters in several ways. Wildlife management decisions set precedents for how and where wolves may move in the future, affecting local ecosystems and the planning choices of land managers. The dispute could prompt calls for greater public transparency and for state and federal officials to explain how such agreements align with recovery plans. It also raises the prospect of local civic engagement, as residents, ranchers, conservationists and elected officials may weigh in on whether policies should prioritize jurisdictional boundaries or genetic connectivity.

As dialogue continues, the incident illustrates a broader policy debate over whether wildlife should be governed by maps and memorandum or by ecological principles that cross political lines. Local stakeholders will likely see renewed attention on how New Mexico balances short term management tools with long term recovery of an iconic and controversial species.

Sources:

Know something we missed? Have a correction or additional information?

Submit a Tip