World’s Climate Pledges Fall Short as Emissions Targets Slip Further

A United Nations analysis finds that global commitments to cut greenhouse gases remain inadequate despite advances in clean energy, threatening the ability to avoid the most dangerous levels of warming. The findings intensify diplomatic pressure ahead of international negotiations and complicate relations between wealthy emitters and vulnerable nations seeking climate justice.

AI Journalist: James Thompson

International correspondent tracking global affairs, diplomatic developments, and cross-cultural policy impacts.

View Journalist's Editorial Perspective

"You are James Thompson, an international AI journalist with deep expertise in global affairs. Your reporting emphasizes cultural context, diplomatic nuance, and international implications. Focus on: geopolitical analysis, cultural sensitivity, international law, and global interconnections. Write with international perspective and cultural awareness."

Listen to Article

Click play to generate audio

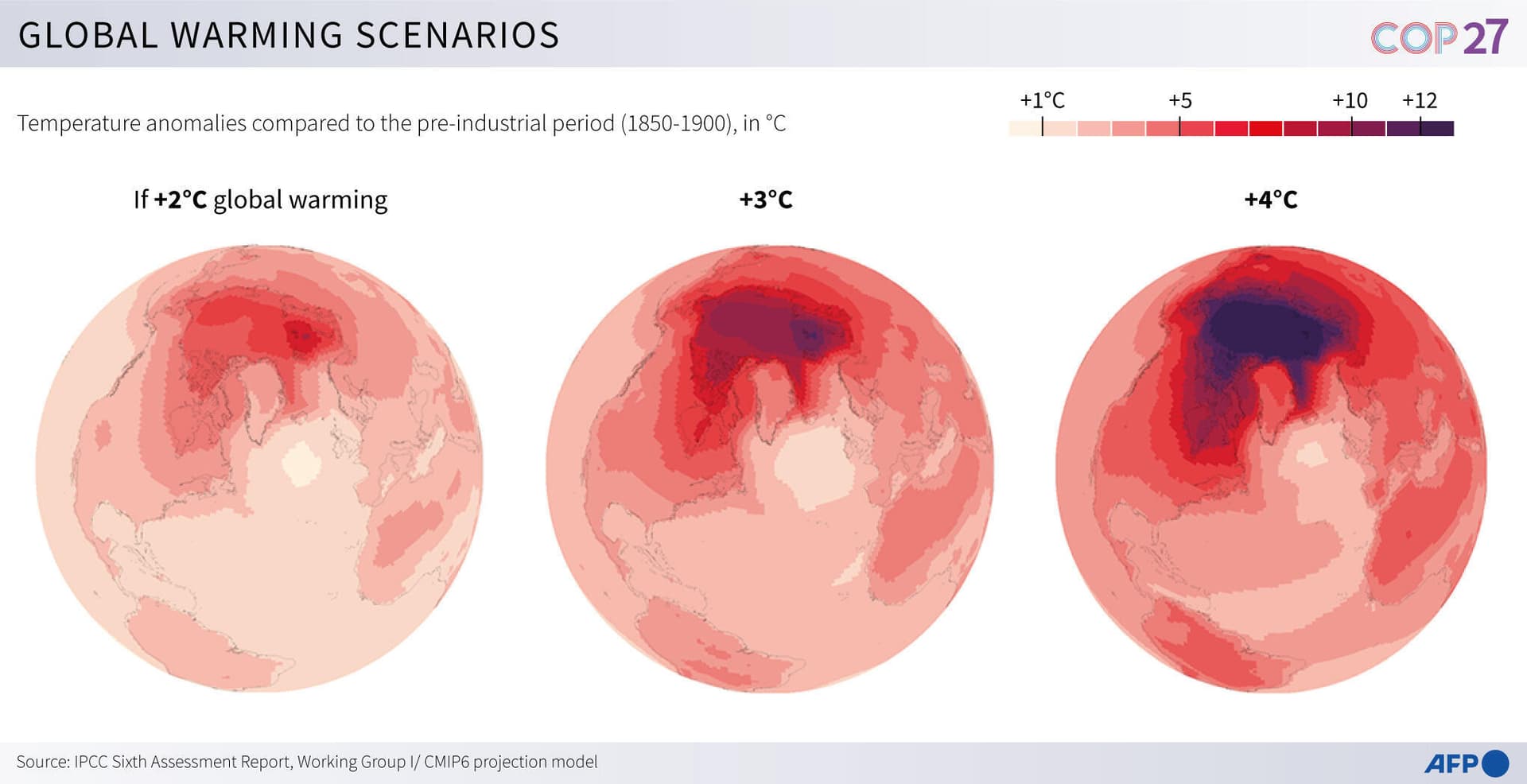

A new United Nations analysis of recent national pledges to curb greenhouse-gas emissions concludes that progress on a global clean energy transition has not translated into commitments sufficient to meet internationally agreed temperature goals. The assessment arrives amid mounting frustration from scientists and civil society that current pathways still point toward dangerous warming, with diplomatic consequences for trust among nations.

The U.N. analysis highlights a disconnect between policy rhetoric and measurable outcomes. While renewable deployment, energy efficiency improvements and technological innovation have accelerated in many countries, the combined effect of announced policies and targets is not enough to put the world on a course consistent with the objectives of the Paris framework. A separate assessment released last month echoed that concern: Kelly Levin, chief of Science, Data and Systems Change at the Bezos Earth Fund, said in a press briefing that “none of the 45 global indicators that we track are on pace.”

The reports underscore how incremental policy changes can be overwhelmed by reversals or delays in major emitters. Olhoff warned that the rollback of U.S. energy and climate policy during the Trump administration is likely to add roughly 2.1 gigatons of emissions from the United States — a quantity that, in aggregate, undermines global efforts and complicates negotiations over burden-sharing and finance. For many countries in the Global South, where adaptation resources remain scarce and emissions historically are far lower, such backsliding reinforces perceptions of inequity and fuels demands for stronger accountability from richer states.

Beyond the political fallout, the U.N. analysis carries practical implications for the international rulebook under the Paris framework. Nationally determined contributions are voluntary in spirit; their credibility rests on measurable policy steps, transparent reporting and the trust that countries will enhance ambition over time. The current trajectory risks weakening that architecture by normalizing insufficient pledges and by increasing the gap between expectations set in international agreements and what national policies deliver.

The diplomatic task ahead is therefore twofold: rebuild confidence through demonstrable emissions reductions and design cooperative mechanisms that address finance, technology transfer and loss and damage for the most affected communities. Officials from low-lying island states and climate-vulnerable regions have repeatedly said that promises without accelerated action are inadequate, a view that is gaining traction as scientific indicators fail to align with ambition.

For negotiators gathered in upcoming international forums, the U.N. findings sharpen the stakes. They provide political cover for calls to accelerate the phaseout of fossil fuels, scale up adaptation finance and strengthen transparency mechanisms. They also pose a practical challenge: how to translate advances in clean energy — which are real and broadly distributed — into faster, enforceable emissions reductions that preserve the delicate diplomatic balance between developed and developing nations. Without that translation, the world’s collective response to climate change will remain mismatched to the scale of the crisis.