Activist Investor Attacks Swatch Governance, Seeks Board Overhaul

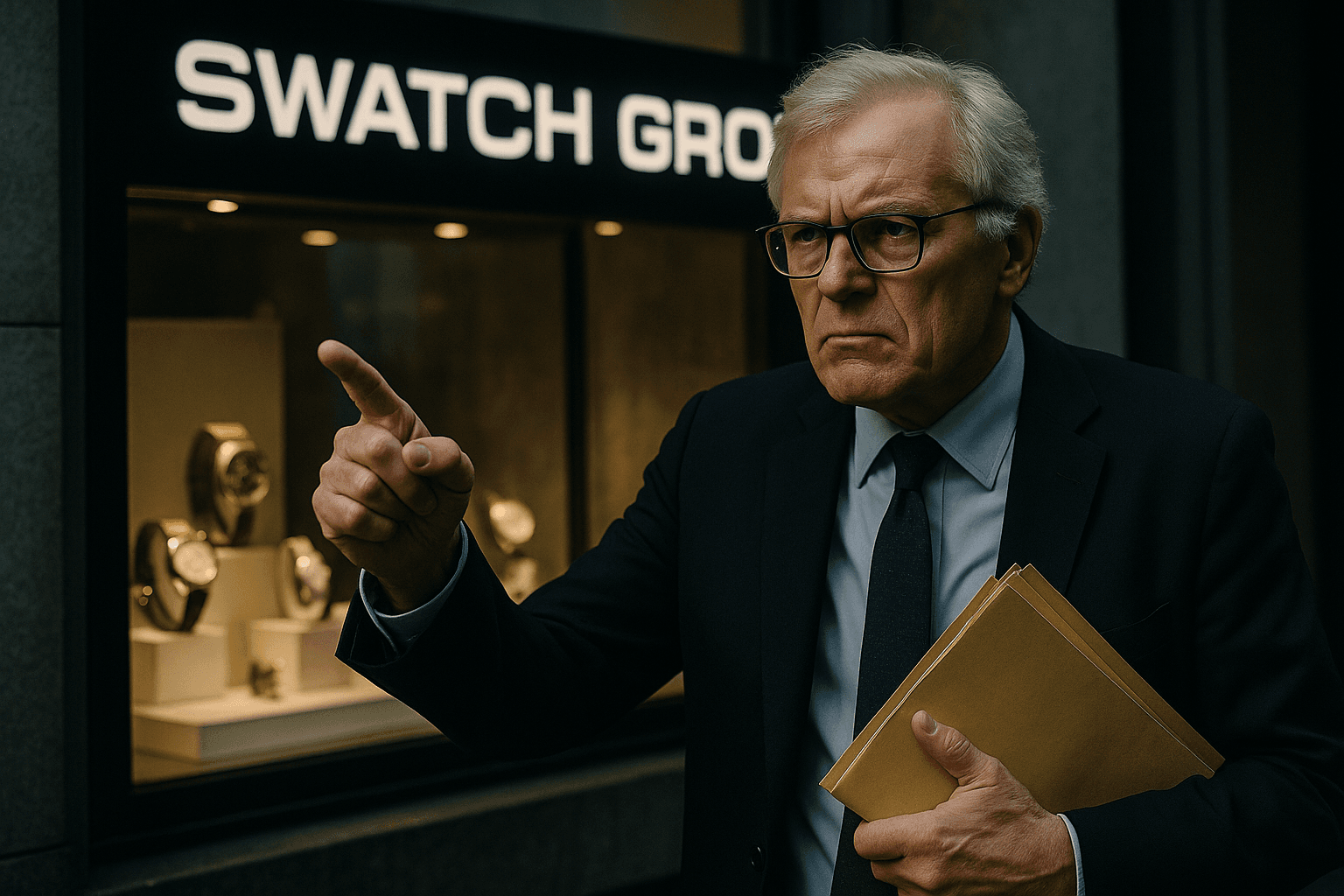

U.S. investor Steven Wood accused Swatch Group of "worst-in-class governance," proposing a package of board and governance reforms after abandoning a bid for a directorship, the Financial Times reported. The move, coming from GreenWood Investors which holds roughly 0.5 percent of Swatch share capital, underscores rising activist pressure on European blue chip companies and could force strategic and oversight changes at the Swiss watchmaker.

Steven Wood, founder of U.S. fund GreenWood Investors, publicly urged Swatch Group to overhaul its board and governance arrangements after characterizing the company as exhibiting "worst-in-class governance," the Financial Times reported on November 29. GreenWood said it holds about 0.5 percent of Swatch share capital and has dropped plans to pursue a board seat, opting instead for a public campaign pressing the group to adopt a package of reforms aimed at lifting performance and shareholder value. Swatch did not publicly respond to the report.

Although GreenWood's stake is modest, the episode is significant because it highlights how small but vocal activist positions can catalyze scrutiny of corporate governance in Europe. Activists increasingly use public proposals and media pressure to prompt change rather than rely solely on proxy fights. For companies in sectors facing secular challenges and tighter margins, such attention can accelerate board refreshes, strategic reviews, and shifts in capital allocation priorities.

For investors and markets the immediate effect is less about the size of GreenWood's holding than about signaling. Governance criticism of this kind can increase the likelihood of management concessions, ranging from clearer strategic guidance to adjustments in executive pay and board composition. In the Swiss context, where governance traditions have typically favored continuity and long tenures, public activist demands can force a recalibration toward greater board independence and shareholder responsiveness. The broader implication is that Swiss and other European firms will face more pressure to demonstrate modern oversight practices that global investors reward.

Policy makers and market regulators will be watching the outcome because these battles test the balance between shareholder rights and corporate stability. If Swatch opts to engage and entertains formal governance changes, it could set an example for peers to pre-empt activist campaigns by raising governance standards. Conversely, a defensive posture could invite more persistent pressure from other investors seeking improved returns. For pension funds and long term investors, the question is whether governance upgrades translate into measurable improvements in margins, return on capital and total shareholder return over the business cycle.

Long term trends in corporate governance suggest that transparency, independent oversight and accountable capital allocation are becoming default expectations for listed industrial and consumer goods companies. Activists such as GreenWood, even with fractional stakes, exploit information asymmetries and media channels to amplify their demands. The Swatch episode therefore matters beyond one company because it underscores a durable shift in investor tactics and corporate responses across Europe.

How Swatch responds will be the key variable. A constructive engagement could lead to board adjustments and revised strategic priorities that align management incentives with shareholder returns. A non response or outright resistance could extend the dispute and increase reputational and market scrutiny, with potential consequences for the premium investors are willing to pay for governance stability and future cash flows.