China Slow Walks Soybean Purchases, Undercuts U.S. Trade Claims

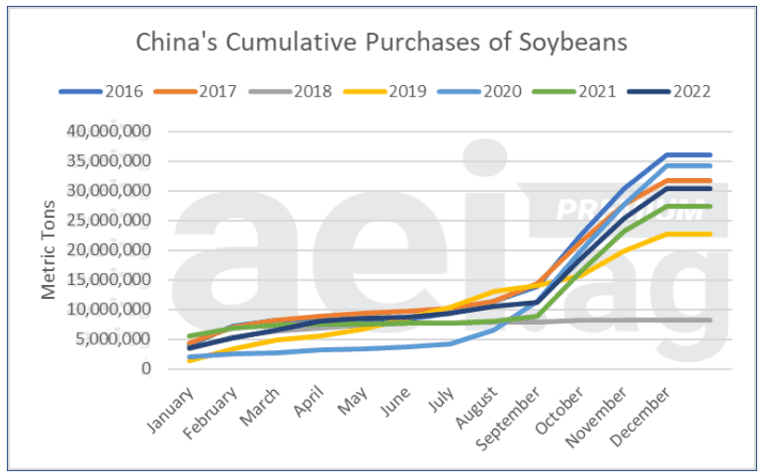

China's state buyers have refrained from the surge of soybean purchases expected under the recent U.S. trade truce, while Beijing's inventories sit at multi year highs. The slow pace of buying threatens a rebound in U.S. agricultural exports, complicates trade negotiations and signals Beijing will use imports as a geopolitical lever.

China has shown little appetite to rapidly reopen its market to U.S. soybeans despite public signs of thawing trade relations, leaving American farmers and commodity markets waiting for demand that has not materialized. Analysts say state procurement activity does not support the purchase program that Beijing and Washington outlined, even as China builds stockpiles at levels not seen in several years.

Arlan Suderman, chief commodities economist at StoneX, wrote in a note on November 11 that there is "little indication that these state buyers are engaged in a program to purchase 12 mmt ahead of the end of this year, let alone 25 mmt more for calendar year 2026." He added, "Thus far we see little evidence of it as the clock continues to tick." The 12 mmt figure refers to 12 million metric tons of soybeans that U.S. officials had expected Beijing to buy under an initial phase of the deal, with an additional 25 million metric tons envisioned for 2026.

Beijing has sent mixed signals. It recently restored import licenses for three U.S. soybean exporters, including Minnesota based CHS Inc., an action market participants took as a tentative positive sign. Yet those bureaucratic moves have not translated into sustained bulk purchases. Instead China appears to be running down its eligibility to buy while maintaining ample domestic supplies, analysts say, creating a cushion that allows officials to modulate imports.

Michael Sobolik, a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute, cautioned that the pattern is likely deliberate. He said China will likely "slow roll soybean purchases to bait the Trump administration into prolonged negotiations" to freeze competitive actions from the Trump administration. That strategy would let Beijing vary volumes in response to the geopolitical temperature, according to commodity analysts at BMI.

The market implications are concrete. U.S. soybean exporters had forecast a near term rebound in shipments, which would alleviate pressure on domestic prices after months of uncertainty. With China sitting on a glut, those shipments are lagging, prolonging revenue challenges for soybean growers in the Midwest. Global soybean markets may see volatility as buyers shift between suppliers, notably Brazil and Argentina, where harvest season and logistics determine when shipments can expand.

From a policy perspective, the episode highlights how China can use commercial flows as bargaining chips in broader strategic competition. The discrepancy between headline trade pledges and visible purchasing behavior undermines a central U.S. argument that the trade truce would quickly channel large volumes of U.S. agricultural goods to China. For Washington, the gap raises questions about how to incorporate enforceable purchase commitments into future negotiations.

Longer term, Beijing's accumulation of reserves reflects a strategy to secure food supplies and stabilize domestic prices amid geopolitical uncertainty. That approach reduces near term import dependency, but it also postpones demand for major exporters such as the United States. For U.S. farmers and policymakers, the lesson is that trade deals can yield headlines without immediate changes in flows, and that market realities will continue to shape the winners and losers in the global oilseed trade.