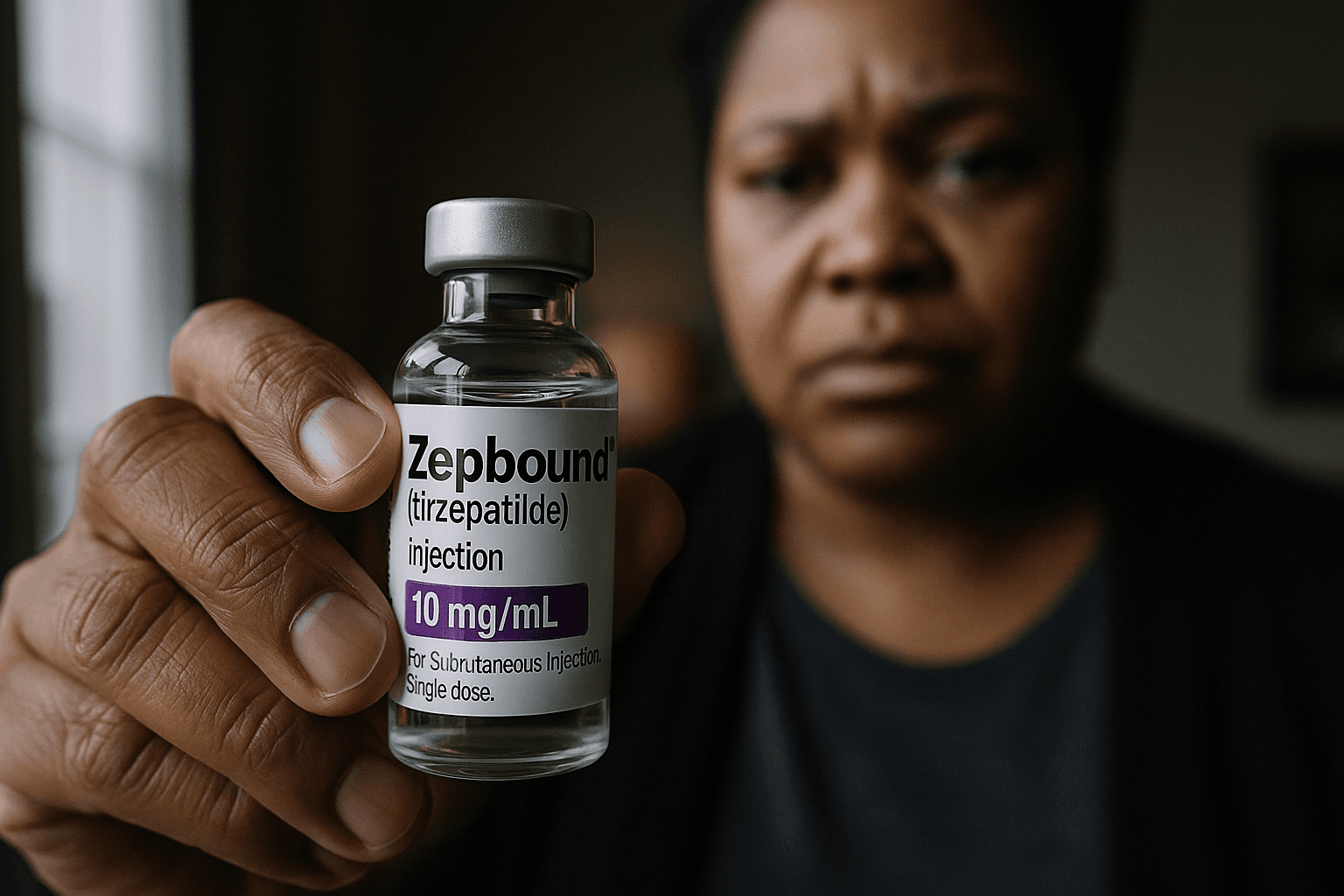

Eli Lilly Lowers Zepbound Vial Prices to Expand Access

Eli Lilly said it cut out of pocket cash prices for single dose vials of its GLP 1 obesity drug Zepbound on its LillyDirect platform, aiming to ease affordability amid soaring demand. The move matters because lower cash prices can help uninsured and underinsured patients seek treatment, while also reshaping payer negotiations and policy debates about drug pricing.

Eli Lilly announced on Dec. 1, 2025 that it had reduced the cash price for single dose vials of Zepbound, its GLP 1 therapy for obesity, on the company run LillyDirect platform. The reductions set the 2.5 milligram vial at $299 a month, down from $349, the 5 milligram vial at $399 a month, down from $499, and higher single dose vials at $449 a month, previously $499. The company framed the changes as part of broader efforts to widen access as demand for weight loss therapies continues to climb.

The announcement followed prior price concessions and a recent agreement between Lilly and the U.S. administration intended to expand affordability of GLP 1 drugs for Medicare, Medicaid and cash pay patients. Industry analysts said the latest cuts were another step toward lowering direct costs for patients who pay out of pocket, a group that has grown as supply and media attention have increased interest in weight loss medications.

Market reaction was mixed, reflecting a tension between volume growth and pressure on profit margins. Investors weighed the prospect of higher patient uptake against the likelihood that sustained price concessions would compress revenue per unit even as sales expand. Payers and pharmacy benefit managers are closely watching the move, because changes in cash pricing can influence negotiations over formulary placement and rebates, and may prompt fresh calls for federal or state policy responses.

Public health specialists said lower cash prices could make a meaningful difference for people without comprehensive insurance coverage, who often face steep out of pocket costs for specialty therapies. Reducing the retail cost of single dose vials can lower the initial barrier to starting therapy for people paying cash, particularly in communities with limited access to specialists who prescribe these medications. Yet advocates and clinicians cautioned that price alone is not the full answer to equitable access. Long term treatment requires medical supervision, insurance coverage for follow up care, and coverage policies that address prior authorization and quantity limits.

The policy implications extend beyond individual affordability. For Medicare and Medicaid, negotiations that incorporate lower list prices or broader discount agreements might change enrollment patterns and program spending, and could inform debates in Congress over drug pricing transparency and federal negotiation rights. For employer sponsored plans and state Medicaid programs, the adjustments may shift bargaining leverage with manufacturers and pharmacy benefit managers as they reassess coverage criteria for GLP 1 therapies.

Public health experts also noted systemic concerns about equitable distribution. Communities of color and low income populations already face higher rates of obesity and barriers to care. While cash price reductions can help some patients, disparities may persist if insurers continue restrictive coverage practices or if providers are unevenly distributed across regions.

Lilly’s move underscored the high stakes in the evolving market for GLP 1 drugs, where manufacturers, payers, policymakers and patients are recalibrating expectations about affordability, access and the role of public programs. As these discussions unfold, attention will remain on whether additional price changes or policy interventions produce wider, more sustainable access for those most affected by obesity.