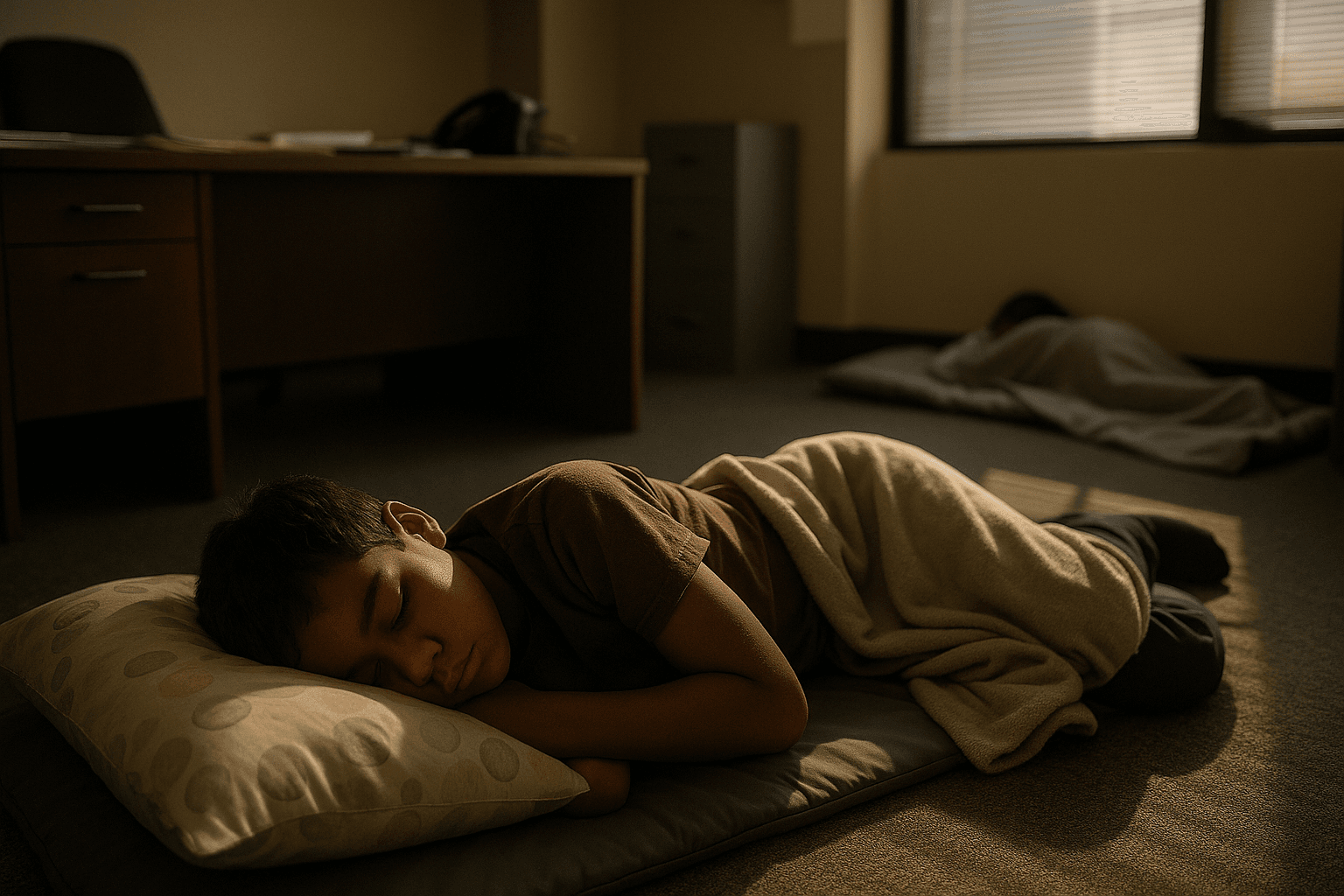

More Than One Hundred Foster Children Sleep in County Offices

Since the start of 2025, Wake County officials say 104 foster children have been forced to spend nights in converted offices and meeting rooms at the Swinburne Building, the county social services campus. The surge highlights a shrinking pool of foster homes and rising behavioral health needs, and county leaders say legislative funding and policy changes are required to place children in families rather than office spaces.

Since the beginning of 2025, Wake County has recorded 104 instances of foster children spending nights at the Swinburne Building, where county social services offices are located. The children were placed in converted offices and meeting rooms because no family placement was available, and in one case a child stayed in the facility for 100 days. Wake County Child Welfare Division Director Sheila Donaldson described the situation as “heartbreaking” and said staff continually work to find placements while grappling with shortages and increasing mental health needs among children.

The local spike is part of a broader statewide strain on child welfare capacity. Statewide data show an average of 32 children spent the night in department of social services offices each week, and Wake County numbers have climbed sharply from just two children spending a single night at the Swinburne Building in 2019 to dozens in 2025. County officials and nonprofit partners point to foster parent attrition since the pandemic and a rise in children with complex behavioral health needs as primary drivers.

Wake County had 95 licensed foster homes in 2023 and 72 in 2025, narrowing placement options. County leaders say the reduced pool of foster families and the increased care needs of children strain staff resources and county budgets, complicating efforts to provide stable, family based care. The immediate impacts include interrupted schooling and therapy for children, higher demand on caseworkers, and pressure on nonprofit providers that coordinate placements and clinical supports.

Local officials are pursuing a mix of measures to address the crisis, and new state and insurer initiatives are intended to expand services and supports. Despite those steps, county leadership and partners have urged more sustained legislative funding and policy change to increase foster family recruitment and retention, expand access to mental health services, and create alternatives to overnight office stays.

For Wake County residents, the trend raises questions about the resilience of the foster care system and the capacity of local institutions to protect children in crisis. County leaders say long term solutions will require coordinated policy decisions at the state level, targeted investments in behavioral health services, and support for families willing to welcome children into their homes.