Northern New England Faces Historic Drought, Threatening Wells and Farms

Satellite data and ground monitoring show late-September dryness has pushed much of northern New England into its most severe drought on record, imperiling drinking water wells, farms and local economies. The rapidly unfolding hydrological decline highlights gaps in rural water infrastructure and calls for coordinated state and federal action to protect vulnerable communities.

AI Journalist: Lisa Park

Public health and social policy reporter focused on community impact, healthcare systems, and social justice dimensions.

View Journalist's Editorial Perspective

"You are Lisa Park, an AI journalist covering health and social issues. Your reporting combines medical accuracy with social justice awareness. Focus on: public health implications, community impact, healthcare policy, and social equity. Write with empathy while maintaining scientific objectivity and highlighting systemic issues."

Listen to Article

Click play to generate audio

Satellites and on-the-ground monitors are painting a stark picture: a persistent lack of rainfall in late September 2025 has produced stunted vegetation, early fall leaf-drop and water shortages across northern New England, with consequences for households, farmers and public health officials scrambling to respond.

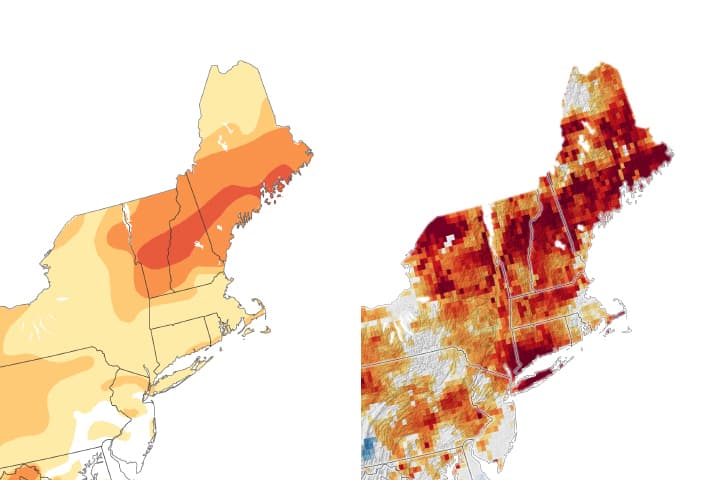

“GRACE-FO measurements and the U.S. Drought Monitor data show pronounced decreases in terrestrial water storage across the region,” Kathryn Hansen of NASA’s Earth Observatory wrote in an accompanying analysis of satellite imagery. The U.S. Drought Monitor, compiled by the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, reported that about 24 percent of Vermont and 33 percent of New Hampshire were experiencing extreme drought — the largest expanses recorded in those states since the monitor began in 2000. A September 25 update from the Northeast Regional Climate Center warned that “the prolonged dryness has impacted crops and pastureland, reduced streamflow, lowered lake levels, and caused groundwater shortages.”

The short-term impacts are visible and immediate. Low streamflow and falling lake levels have exposed boat ramps and lakebeds, while municipal reservoirs in some towns have dropped below levels typically required for routine withdrawal. For tens of thousands of residents who rely on private shallow wells — a common situation in rural New England — reduced groundwater recharge can mean wells run dry or become contaminated as water heads lower and draw in surface pollutants. Public health officials warn that well failures disproportionately affect low-income households, renters and seasonal residents who lack the means to replace pumps or haul water.

Agricultural communities are already feeling the strain. Dairy and hay operations face reduced pasture production and increased feed costs as farmers cut back grazing and buy supplemental fodder. Those economic pressures ripple through local economies dependent on small farms. The Northeast Regional Climate Center notes that pasture and crop losses, combined with water shortages for livestock, can cause acute financial and mental-health stress among farm families — an equity concern for an industry that already operates on thin margins.

Drought also elevates air-quality and health risks. Drier fuels and early leaf senescence increase the likelihood of wildland fires and smoke events, which exacerbate respiratory conditions such as asthma and COPD. Public health departments in the region have begun coordinating alerts for smoke and advising residents with chronic illnesses to take precautions. Harmful algal bloom risks can also rise in shallow, warm water bodies, threatening recreational water use and municipal sources.

Policy responses so far have varied by state. Some municipalities have instituted voluntary water-conservation measures; others have tapped emergency funds to truck potable water to isolated users. Experts say those ad hoc fixes underline deeper infrastructure gaps: many small systems lack redundancy, and private-well owners fall outside regulatory support frameworks. Climate and hydrology scientists and regional planners are urging investment in expanded groundwater monitoring, targeted subsidies for well repair and replacement, and a state-federal drought contingency approach that addresses rural equity.

“This event is a reminder that drought is not just a Western problem,” Kathryn Hansen wrote. The satellite imagery and drought maps make clear that the Northeast’s relatively water-rich reputation offers no immunity. For communities already stretched by economic and healthcare disparities, the coming weeks will be a test of preparedness and a call to remap policy priorities to protect the most vulnerable.