Optima Lake's future uncertain as water drops limit reservoir

Optima Lake was completed but never filled; shrinking Beaver River flows and Ogallala aquifer decline have left the Corps managing a dry flood-control and wildlife area important to locals.

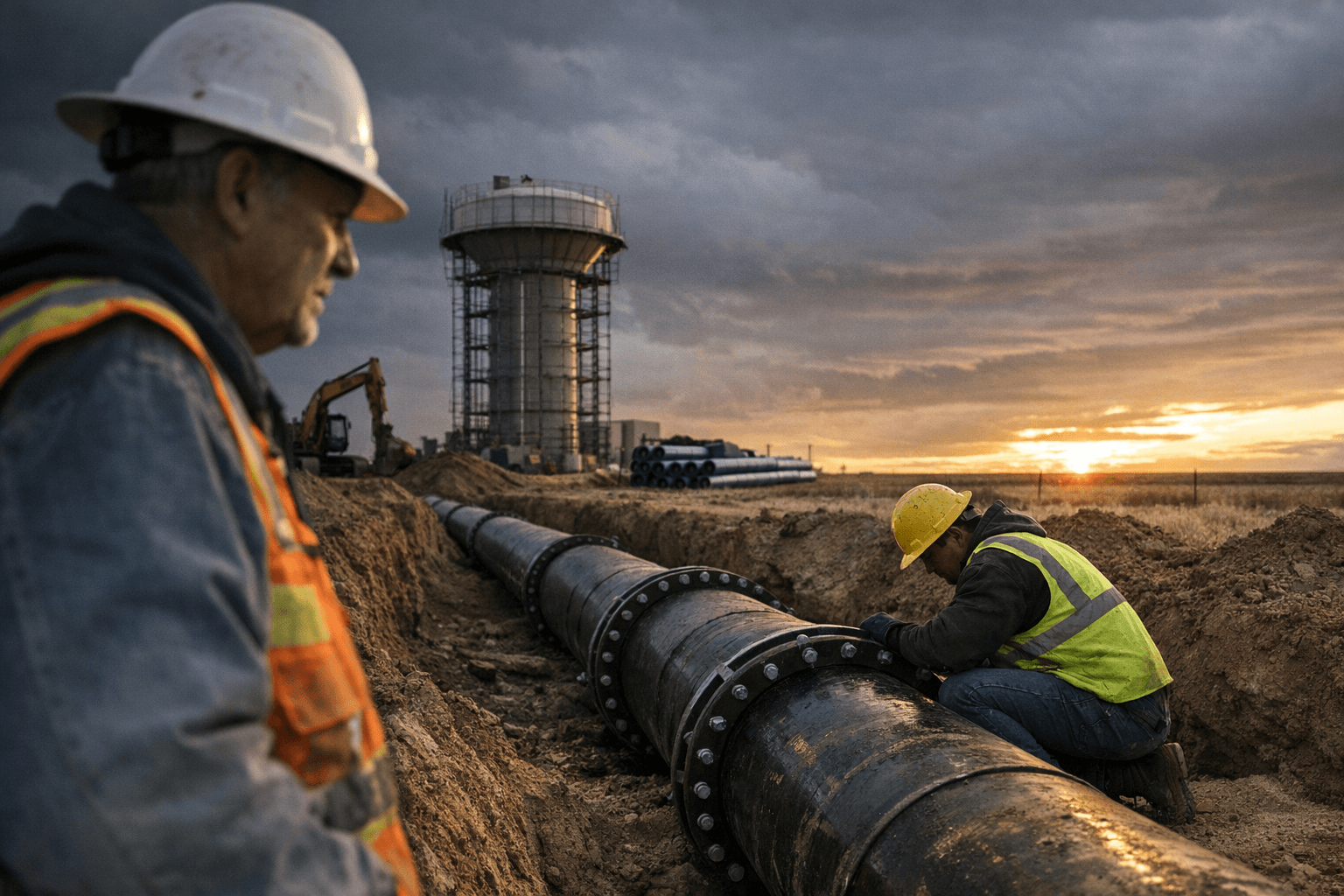

Optima Lake in Texas County stands as a built but unrealized piece of infrastructure: completed in 1978, the reservoir never reached its designed pool because upstream flows on the Beaver (North Canadian) River fell sharply after construction. Those declines have been linked largely to groundwater reductions in the Ogallala Aquifer, turning the project into a mostly dry flood-control basin and wildlife area rather than the recreational lake residents were promised.

The site sits northeast of Hardesty and about 20 miles east of Guymon. Over decades the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has continued to maintain the project for flood risk reduction while state and federal partners manage surrounding lands for wildlife and hunting. Recreational facilities that once drew anglers and campers were removed for safety in 2010 after inspections showed structures could not be sustained without reliable water levels.

Institutionally, Optima is a case study in how long-term hydrology shifts outpace project assumptions. The Corps has conducted appraisal and disposition work, including a 2010 appraisal and later disposition study activity, to evaluate options that range from continued minimal operation to possible deauthorization or transfer of lands. Those options pose complex choices for federal, state, and local authorities about stewardship responsibilities, maintenance budgets, public access, and ecological management of the dry basin and adjoining public lands.

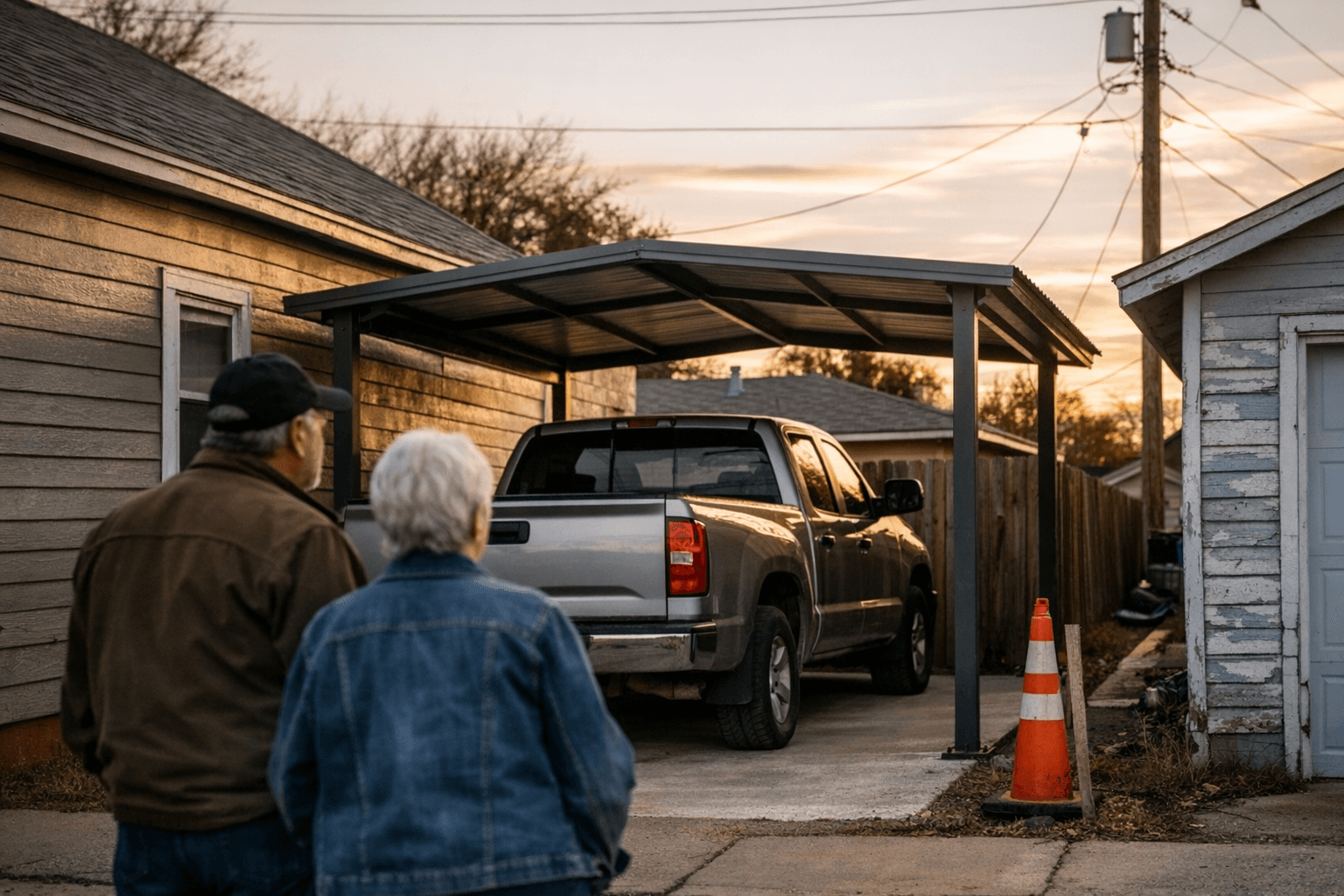

For Texas County residents the issue is practical as well as symbolic. The lost lake represents forgone recreation and potential tourism revenue for communities near Hardesty and Guymon. Land managers and sportsmen still use the area for hunting and wildlife habitat, but the absence of a reliable reservoir narrows opportunities for boating, fishing economies, and the seasonal traffic local businesses rely on. The situation also highlights broader policy tensions: groundwater pumping, aquifer conservation, and regional water allocations that affect surface flows downstream.

Decision-making about Optima will require transparent coordination among the Corps, state wildlife and land agencies, county officials, and the public. Community input matters because any move toward transfer or deauthorization will reshape local access and future land use. Voters and elected officials in the Panhandle have repeatedly grappled with water policy tradeoffs; Optima underscores why water management belongs on the ballot and in county conversations about land and economic development.

Our two cents? Keep the pressure local and practical. Ask county commissioners and state representatives for regular updates, attend Corps public meetings when they occur, and support local initiatives that link groundwater conservation to long-term regional planning. That kind of sustained civic engagement gives the community leverage to shape what happens next at Optima.

Sources:

Know something we missed? Have a correction or additional information?

Submit a Tip