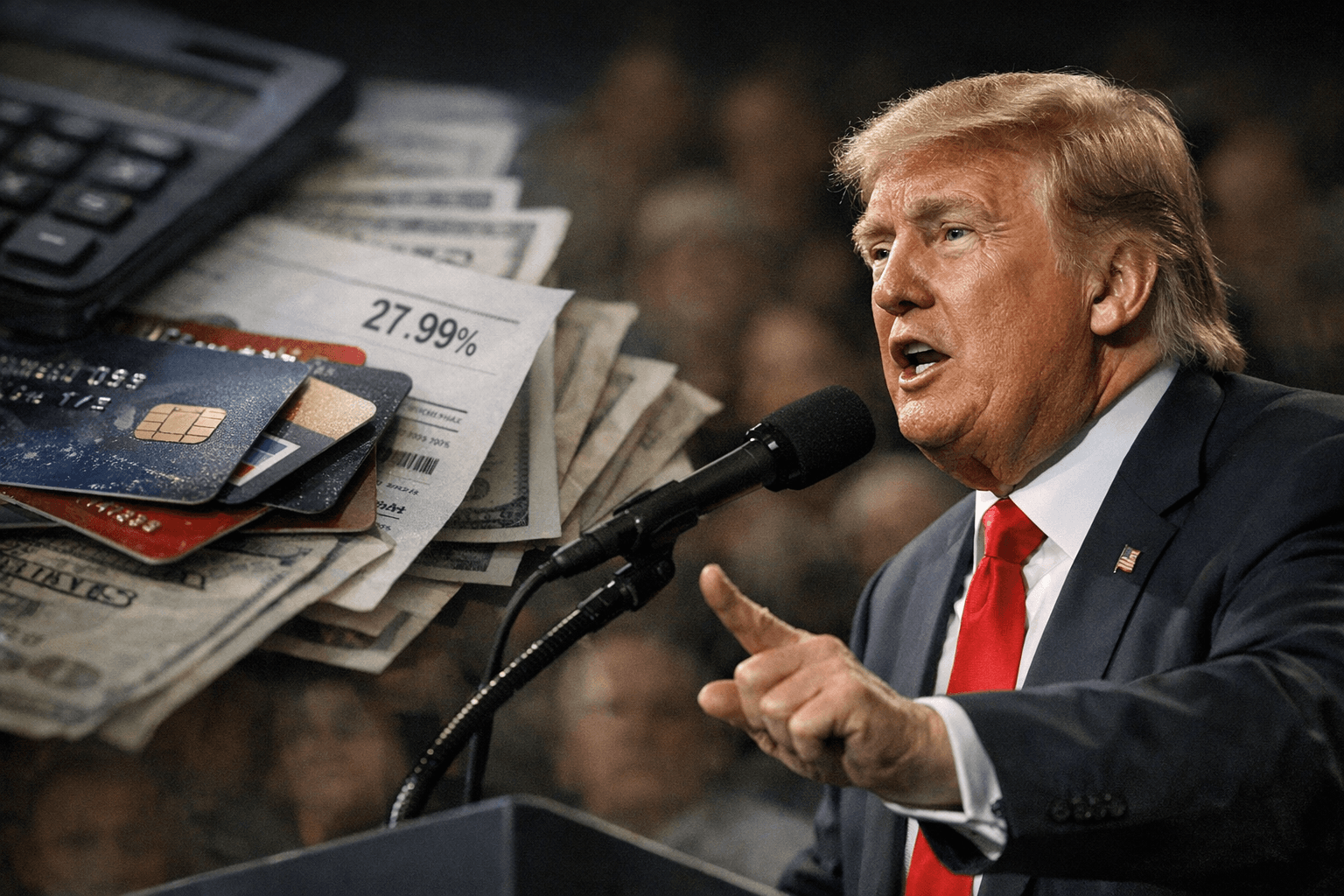

Trump proposes one-year 10% cap on credit-card interest rates

Trump called for a one-year 10% cap on credit-card APRs to stop firms “ripping off” consumers; the plan drew praise from some lawmakers and unified industry opposition.

President Donald Trump revived a campaign pledge on Truth Social proposing a temporary, one-year cap of 10 percent on credit-card annual percentage rates, saying it would stop “Credit Card Companies that are charging Interest Rates of 20 to 30%” from “ripping off” the public. He said he hoped the cap would be in place by Jan. 20, but the White House provided no details on how the limit would be implemented or whether it would require congressional legislation.

The proposal drew quick praise from some Republican allies and progressive critics who have pushed similar limits, while the banking and credit-card industry issued unified opposition. Sen. Roger Marshall (R-Kan.) framed the effort as lowering costs for American families and reining in “greedy credit card companies.” At the same time, the American Bankers Association and allied groups warned that “If enacted, this cap would only drive consumers toward less regulated, more costly alternatives.”

The clash underscores competing views of how best to address rising household debt and high borrowing costs. Seventy-nine to 82 percent of Americans carry credit cards, and outstanding credit-card debt totaled about $1.23 trillion at the end of last year’s third quarter, according to Federal Reserve figures. Average credit-card APRs were described by industry observers as roughly 19.5 percent to 21.5 percent, with consumers in poor credit standing facing rates near 30 percent. A Vanderbilt Law School analysis referenced by proponents estimated that a strict cap could save consumers on the order of $100 billion annually; other estimates place potential savings in the tens of billions.

Banks and card issuers say such a blunt cap would prompt rapid changes in how they extend credit. Major issuers that depend on interest income, including JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup and Capital One, would face immediate pressure on revenue and risk models. Analysts warn banks could curtail or eliminate unsecured credit lines, tighten underwriting, or shift customers toward secured products. Payment networks Visa and Mastercard, which earn primarily transaction fees, would feel indirect effects: lower interest costs might reduce balances and transaction volume in some scenarios, or spur spending in others, leaving outcomes mixed.

Regulatory and legal questions loom large. The administration provided no roadmap for enactment, leaving open whether the cap would arrive through executive action, rulemaking by an agency, or an act of Congress. If Trump sought to impose the cap administratively, critics say courts could find limits on the executive branch’s authority to set across-the-board interest ceilings. Legislatively, competing bills in the House and Senate — including a five-year 10 percent cap proposed by Sens. Bernie Sanders and Josh Hawley — indicate a fractious path forward.

Market reaction was immediate. Financial firms signaled they would mobilize resources to resist statutory or regulatory limits, and analysts expect litigation and political fights that could delay or defeat any measure. Consumer advocates and some lawmakers argue a temporary cap would deliver fast relief to struggling households, while opponents caution it risks pushing borrowers toward payday lenders, buy-now-pay-later plans and other higher-cost alternatives.

With little detail on exemptions, transition mechanics or enforcement, the proposal has set the stage for an intense policy debate over the trade-offs between cutting consumer borrowing costs and preserving access to unsecured credit. The next steps likely include legislative negotiations, industry lobbying and early legal challenges if the administration attempts an administrative route.

Know something we missed? Have a correction or additional information?

Submit a Tip