Ugandans vote amid heavy security in election testing Museveni’s hold

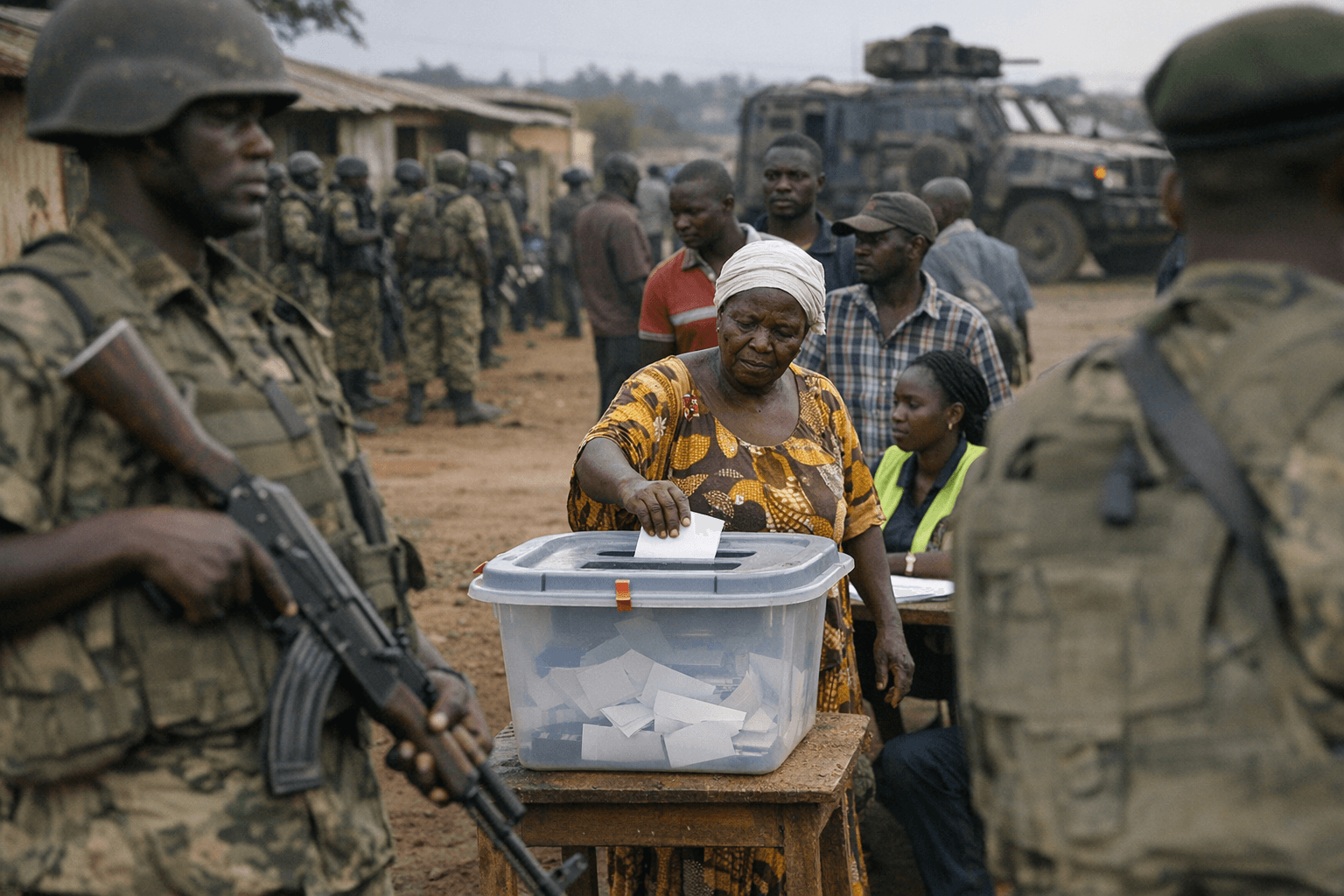

Ugandans are voting under heavy security and communications blackouts as President Museveni seeks another term, exposing deep divisions over democracy and stability.

Ugandans are voting in a tightly contested general election that is being watched as a decisive test of President Yoweri Museveni’s grip on power. The country has seen a fraught campaign marked by heavy security deployments, widespread arrests, restrictions on communications and fears that the ballot will do little to alter the balance of long-standing rule.

Museveni, who has governed since 1986 and is often described as one of Africa’s longest-serving leaders, is seeking another term that critics say extends his rule into a fifth decade. His government has been accused of human rights abuses and of reshaping electoral rules to entrench incumbency; authorities deny those charges and have defended security operations as necessary responses to public disorder, encouraging the use of tear gas rather than live ammunition to disperse opposition events.

The principal challenger is Robert Kyagulanyi Sentamu, known as Bobi Wine, a musician-turned-politician who built a following among younger voters frustrated by unemployment and perceived corruption. Wine has described the campaign as a “war,” pointing to repeated arrests of supporters, violent disruptions of rallies and at least one campaign-related death during the run-up to voting. Hundreds of his supporters have been detained, and observers describe chaotic scenes when security forces moved against opposition gatherings.

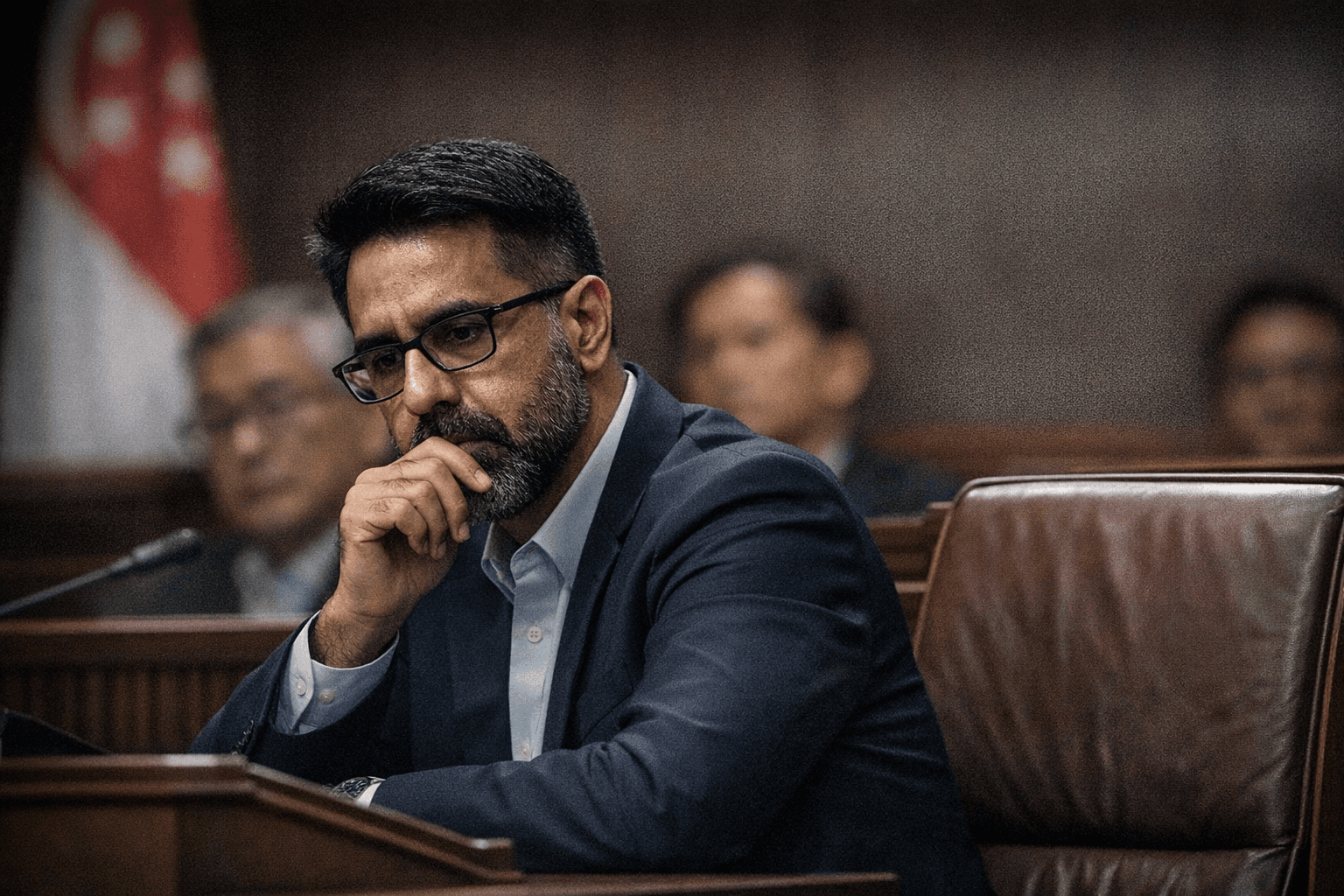

Another notable contender, lawyer Nandala Mafabi, campaigned on an economic platform he summed up as “Fixing the economy; money in our pockets.” Mafabi says he has been “targeted by police,” recounting an incident in which his car came under gunfire in Amudat, and warned that “challenging Museveni comes with a lot of risks.” Six other candidates also contested the presidency, but the race has been dominated by the standoff between the president and Wine’s youthful coalition.

Authorities cut internet access and limited mobile services on the eve of the vote, citing a desire to curb what they described as misinformation. Observers and opposition figures argue the communications blackouts and curbs on live broadcasting of protests were aimed at constraining information flows and limiting opposition organizing. The U.N. Human Rights Office said the elections were taking place amid “widespread repression and intimidation,” reflecting international concern about the environment for free political competition.

About 21.6 million Ugandans are registered to vote, in a nation of more than 45 million people in which nearly half the population remains under 18. That youthful cohort has been a central force in recent opposition politics, driven by economic grievances and hopes for change. The coming start of crude oil production from fields operated by foreign companies has added urgency to debates over resource management and the economic future.

Legal and institutional changes in recent years, including the removal of presidential age and term limits, have reshaped the electoral landscape and raised questions about the durability of democratic checks. Washington and other capitals point to past elections marred by violence and alleged irregularities, and diplomats are watching how authorities handle counting and any disputes.

As polls close and results are tallied, the most immediate risks are political contention over credibility and potential unrest if large segments of the electorate reject the outcome. The vote is not only a domestic contest over leadership: it is a test of Uganda’s institutions, of regional stability and of international willingness to press for elections that reflect the will of voters rather than the endurance of one man.

Know something we missed? Have a correction or additional information?

Submit a Tip