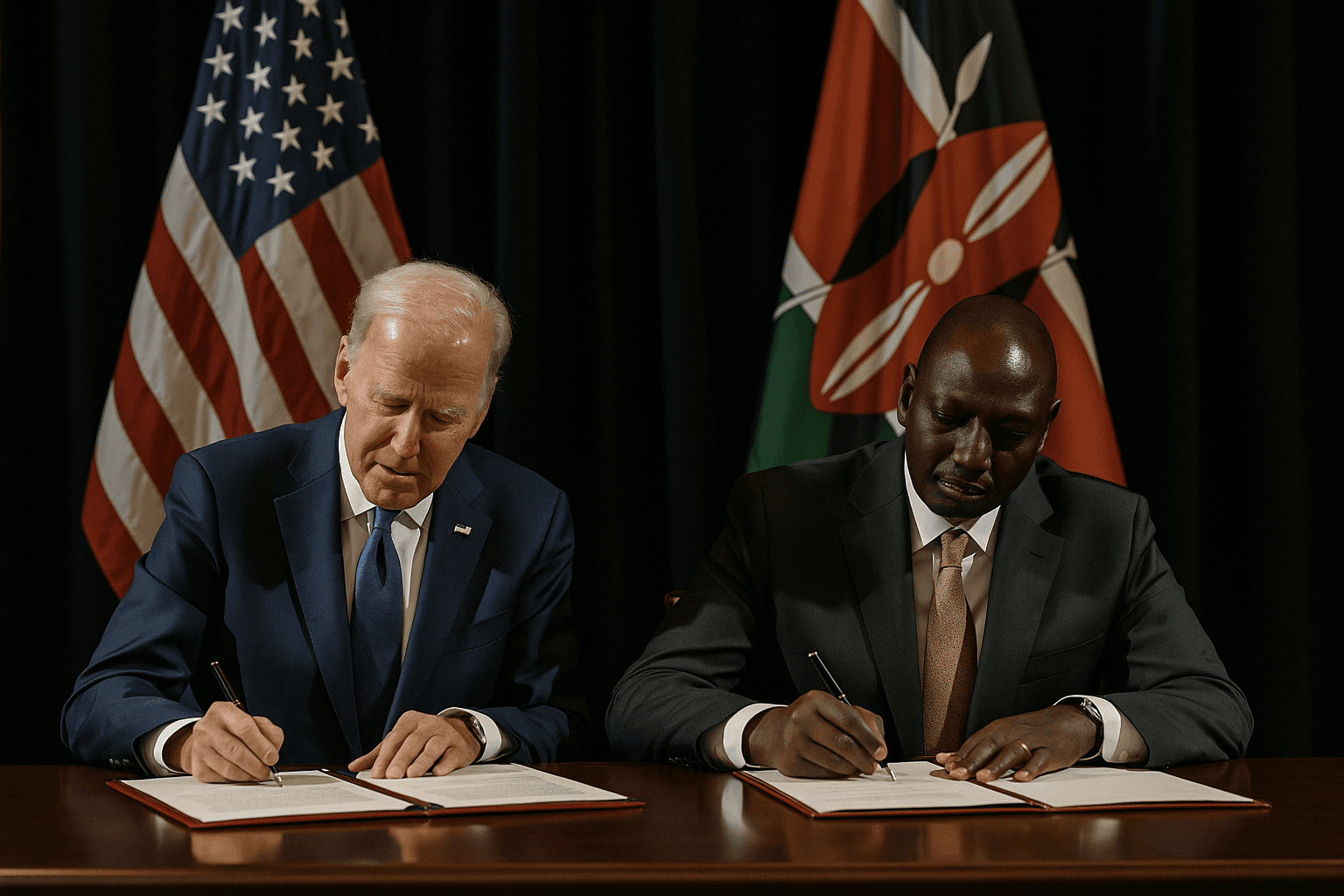

U.S. and Kenya Launch $2.5 Billion Health Partnership, First of Series

The United States and Kenya signed a five year, $2.5 billion bilateral health cooperation agreement aimed at combating HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis while strengthening health systems. The pact matters because it signals a new U.S. approach to global health funding with potential benefits for services on the ground and risks for broader international coordination and equity.

On December 4, 2025, the governments of the United States and Kenya signed a five year, $2.5 billion bilateral health cooperation agreement that U.S. officials described as the first in a planned series of new global health deals. Under the arrangement the U.S. committed roughly $1.7 billion and Kenya pledged $850 million to fight infectious diseases including HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis, and to bolster health system capacity across the country.

Officials framed the pact as a country led model that emphasizes partnerships with faith based organizations and other locally rooted providers. In a year marked by a major reorganization of American foreign aid infrastructure, the agreement reflects a fundamental shift away from the prior architecture, after the U.S. dismantled USAID as a standalone agency earlier in 2025. The new structure aims to move funding toward bilateral agreements and closer alignment with host country priorities.

Kenyan leaders welcomed the package as a boost for domestic health programs and for deeper economic ties, saying the injection of funds would expand service delivery and support local health workforce development. For clinicians and community health workers in remote counties, the commitment could mean more medicines, diagnostics and training over the five year period, with potential real world gains in disease control and mortality reduction.

At the same time, some global health experts expressed concern that the new bilateral model may fragment longstanding multilateral funding streams that many countries rely on. Multilateral mechanisms historically pooled resources for cross border procurement, epidemic surveillance and regional disease control efforts. Fragmentation of funding could complicate supply chains and impede coordinated responses to outbreaks that do not respect national borders.

Public health specialists and advocates for marginalised communities stressed that the design and implementation of the program will determine its equity impact. Directing funds through faith based and country led providers can increase reach into underserved areas, but it can also raise questions about the inclusivity of services and protections for vulnerable populations if safeguards are not explicit and enforced. Civil society groups have urged transparent accountability measures, clear standards on non discrimination, and community participation in program governance.

Policy analysts note the pact also has broader implications for U.S. influence in global health. By pursuing a series of bilateral accords, Washington may win short term diplomatic gains and tailored interventions, yet risk weakening pooled international platforms that finance regional health infrastructure and research. For Kenyan health officials the immediate calculus centers on leveraging the investment to shore up clinics, expand testing and treatment, and strengthen supply chains for essential drugs.

As the five year program unfolds, monitoring by independent evaluators and engagement by community stakeholders will be critical to ensure that promised funds translate into measurable improvements and that gains are shared equitably. The pact marks a new chapter in global health finance, one that will test whether country led bilateralism can deliver both targeted results and the collective solidarity needed to confront transnational health threats.