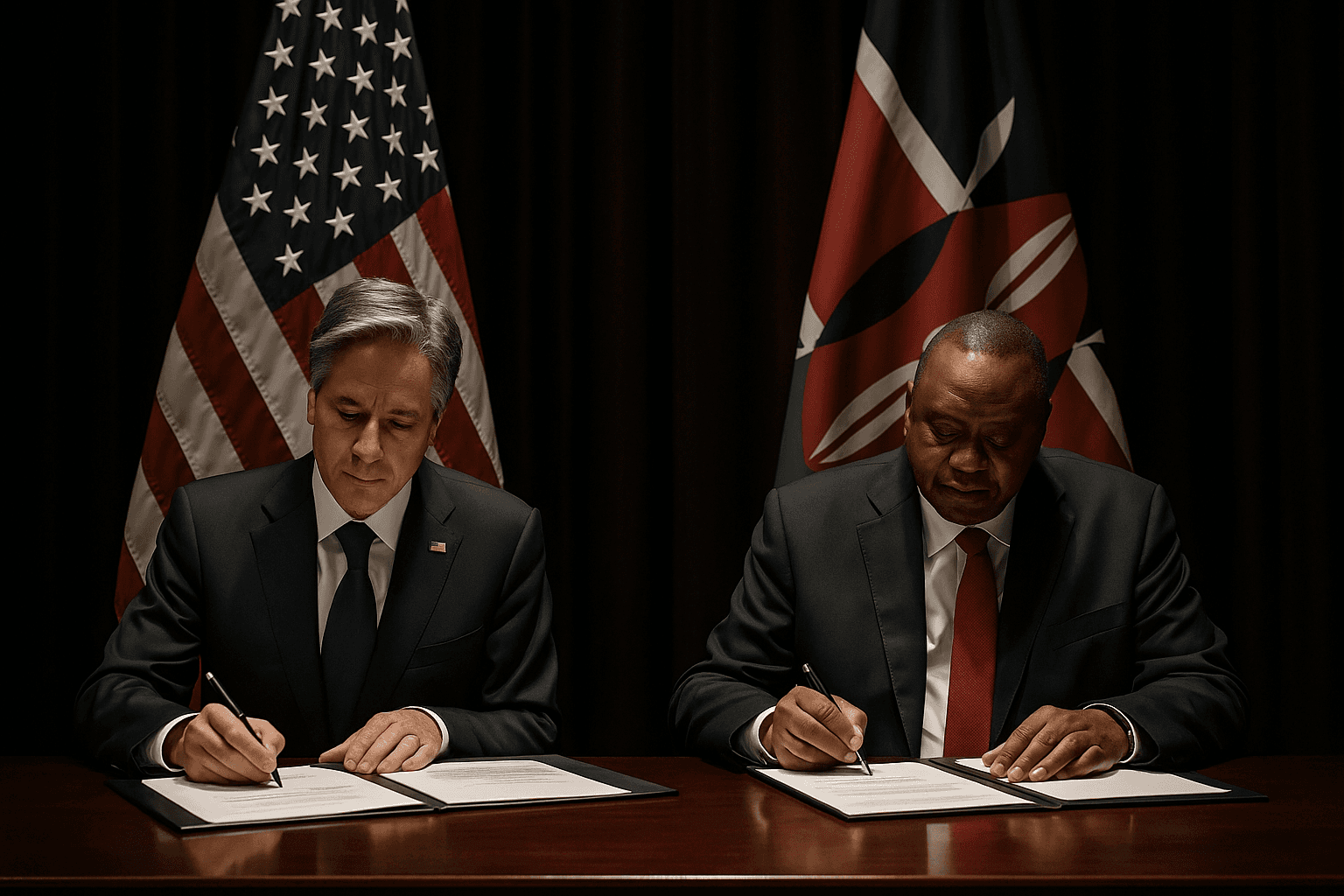

U.S. and Kenya Sign $2.5 Billion Health Pact, A Model for Others

The United States and Kenya sign a five year, $2.5 billion health cooperation agreement today, a blueprint the administration says will be replicated with other countries. The deal shifts services away from traditional aid channels toward partners aligned with U.S. policy, raising urgent questions about continuity for HIV and maternal health programs.

The United States and Kenya sign a five year, $2.5 billion health cooperation agreement today that U.S. officials describe as the first of many planned America First global health deals. The pact will direct roughly $1.7 billion in U.S. assistance alongside about $850 million in Kenyan contributions and focuses on prevention and treatment of infectious diseases including HIV AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis.

The agreement marks a sharp break with the aid architecture that has guided U.S. global health work for decades. It replaces many programs formerly managed through the United States Agency for International Development, an agency the administration has dismantled this year. Officials said the new model prioritizes aid to countries aligned with U.S. policy priorities and emphasizes partnerships with faith based providers. All clinics participating in Kenya's national health insurance scheme will be eligible to receive funding under the pact.

Administration documents and officials frame the arrangement as a more efficient, partnership oriented approach that concentrates resources on countries deemed strategically important to U.S. interests. The deal is structured as a five year cooperation agreement rather than a set of discrete grants, and its design is meant to be replicable as Washington pursues similar agreements elsewhere.

But the announcement immediately drew concern from global health advocates about continuity of services. Critics say the dismantling of USAID and the pivot to new contractual models have already led to the defunding of hundreds of global health programs, and they warn that transitions of this scale can disrupt antiretroviral treatment, maternal care and community health services that depend on steady funding and local expertise.

Sources told the Associated Press that some of Africa's largest countries including Nigeria and South Africa are not expected to be included in the initial wave of agreements because of political differences with the United States. Excluding those regional powerhouses could complicate efforts to mount continentwide responses to epidemics and could shift influence in health and diplomatic networks to other external donors.

The emphasis on faith based providers is likely to reshape service delivery in Kenya, where church affiliated clinics and hospitals already play a major role in treating patients outside major cities. Supporters argue those providers have established trust and reach into underserved communities. Opponents worry that prioritizing faith based organizations could limit services for sexual and reproductive health or create barriers for marginalized groups.

Kenyan government officials framed the pact as a major infusion of resources for longstanding public health priorities, while U.S. strategists promoted it as a template to concentrate American aid where it serves broader diplomatic and security objectives. As Washington prepares to offer similar agreements to other partners, health officials and advocates say close monitoring will be essential to ensure that short term strategic calculations do not undermine decades of progress against HIV, malaria and maternal mortality.