Frank Gehry Dies at 96, Architecture Loses Its Sculptor of Cities

Frank Gehry, the Canadian American architect whose bold, sculptural buildings transformed skylines and municipal strategies for growth, died at 96 after a brief respiratory illness. His passing marks the end of an era in which signature architecture became a central tool for cultural prestige, urban regeneration, and private sector influence over public space.

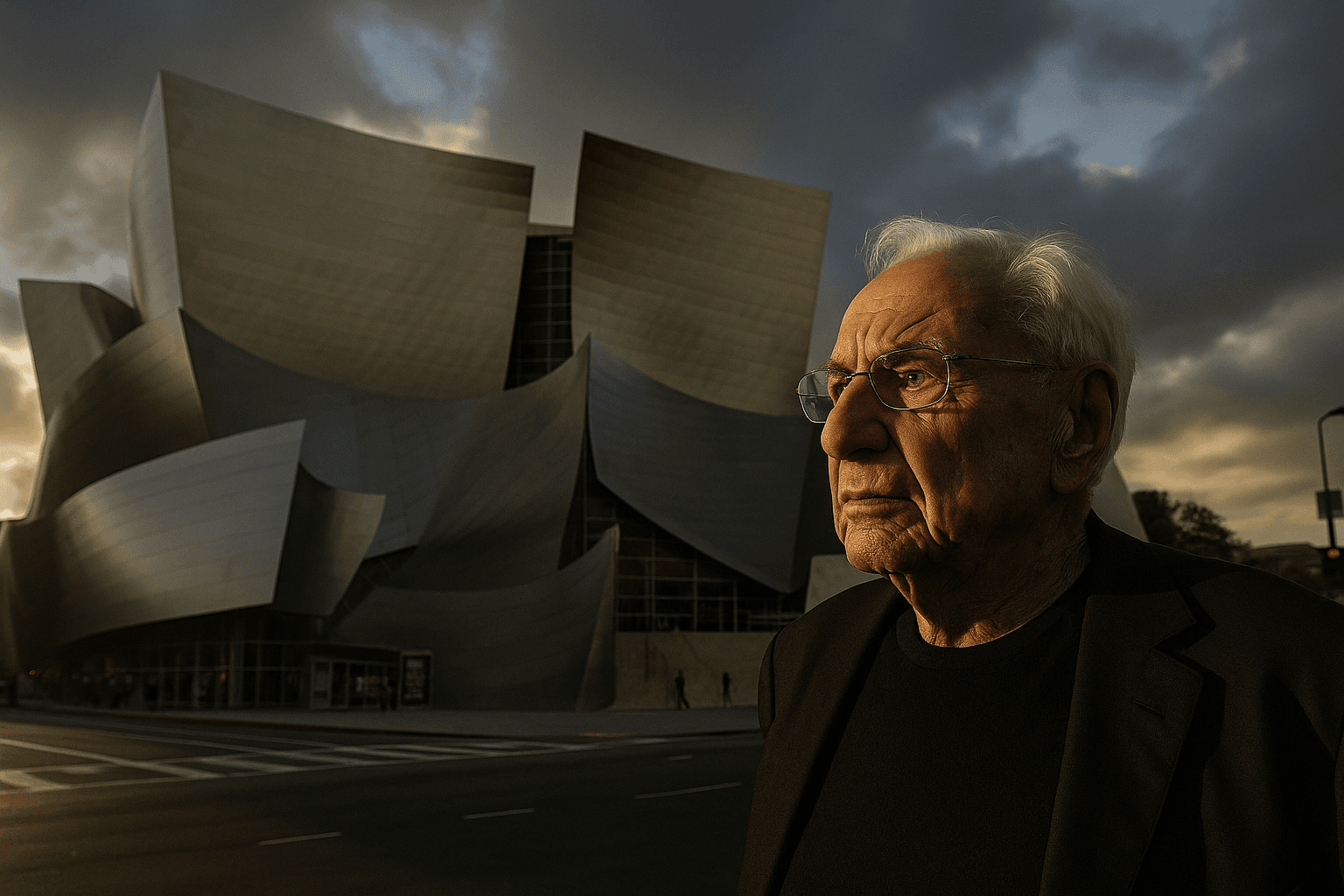

Frank Gehry, the maverick architect whose exuberant forms rewrote the rules of contemporary building design, died on December 5 at his home in Santa Monica. He was 96. Gehry Partners chief of staff Meaghan Lloyd told Reuters that the cause was a brief respiratory illness.

Born Frank Owen Goldberg in Toronto, Gehry built a career that would take him from modest commissions and shopping centers to the global stage. His resurrection of a stalled career after reworking his own house in the 1970s signaled a new generative approach, one that prized surprise, material experimentation, and a theatrical sense of movement. That reinvention culminated in work that polarized critics, enthralled the public, and reshaped the way cities think about architecture as an engine of economic and cultural renewal.

Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao became shorthand for what came to be called the Bilbao effect, the idea that a single iconic building can catalyze tourism, investment, and civic identity. The Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles confirmed his ability to marry monumental civic ambition with an unmistakable aesthetic. Over a career that included the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, Miami’s New World Center, and corporate commissions such as the expansion in Menlo Park for Facebook, Gehry moved seamlessly between cultural institutions, municipal projects, and private clients.

His 1989 Pritzker Prize affirmed his standing in the profession, even as debate about his approach intensified. Admirers celebrated his capacity to make architecture feel cinematic and immediate, to transform structure into spectacle. Critics argued that his formal audacity sometimes subordinated programmatic clarity and cost efficiency. That tension between form and function became a central fault line in contemporary architectural discourse, and Gehry’s work often sat squarely at its intersection.

Gehry’s influence extended beyond aesthetics into industry practice. He pushed architects and fabricators to adopt new digital modeling tools to realize complex geometries, accelerating a wider technological shift in design and construction. At the same time, his high profile projects underscored growing trends in the commissioning of architecture, from city governments seeking landmark status to technology firms and private patrons who use conspicuous design to signal corporate identity and civic ambition.

Culturally, Gehry helped normalize the celebrity architect, a figure whose name carries as much value as a building program. That visibility expanded public engagement with architecture, sparking curiosity and contention in equal measure. It also amplified debates about who benefits from signature projects, with questions about cost, maintenance, and the displacement effects of tourism becoming part of the legacy of Bilbao style interventions.

As cities and clients today wrestle with climate urgency, equity, and the limits of spectacle, Gehry’s career offers both inspiration and caution. His buildings remain landmarks, capable of delight and provocation, while the conversations they provoke will continue to shape architectural priorities in the decades ahead. He is survived by family, and by a built record that will remain a central subject for the profession and the public alike.