Nature Retracts Influential Climate and Economy Paper After Data Error

Nature retracted a widely cited climate and economy paper on December 5, 2025 after the authors found a country level data error that materially altered headline projections. The correction sharply reduced the study's most extreme estimate of global GDP losses by 2100, prompting fresh questions about modeling practices and how policymakers should treat long run economic forecasts tied to climate scenarios.

Nature issued a retraction on December 5, 2025 for a high profile study that had produced headline grabbing estimates of global economic damage from climate change by 2100. The journal and the paper's authors said an inadvertent error in the underlying dataset, a country level entry that skewed results, undermined the study's central conclusions. After correcting the dataset the most extreme projection fell substantially and the authors indicated they intend to resubmit a corrected analysis.

The original paper had been widely cited in academic and policy circles because it reported particularly large projected losses under high warming scenarios. Those figures had been used in public debates about the scale and timing of mitigation and adaptation investments. The retraction released by Nature said the corrected numbers no longer supported the same policy bluntness as the original findings, and that the error was material to the study's conclusions.

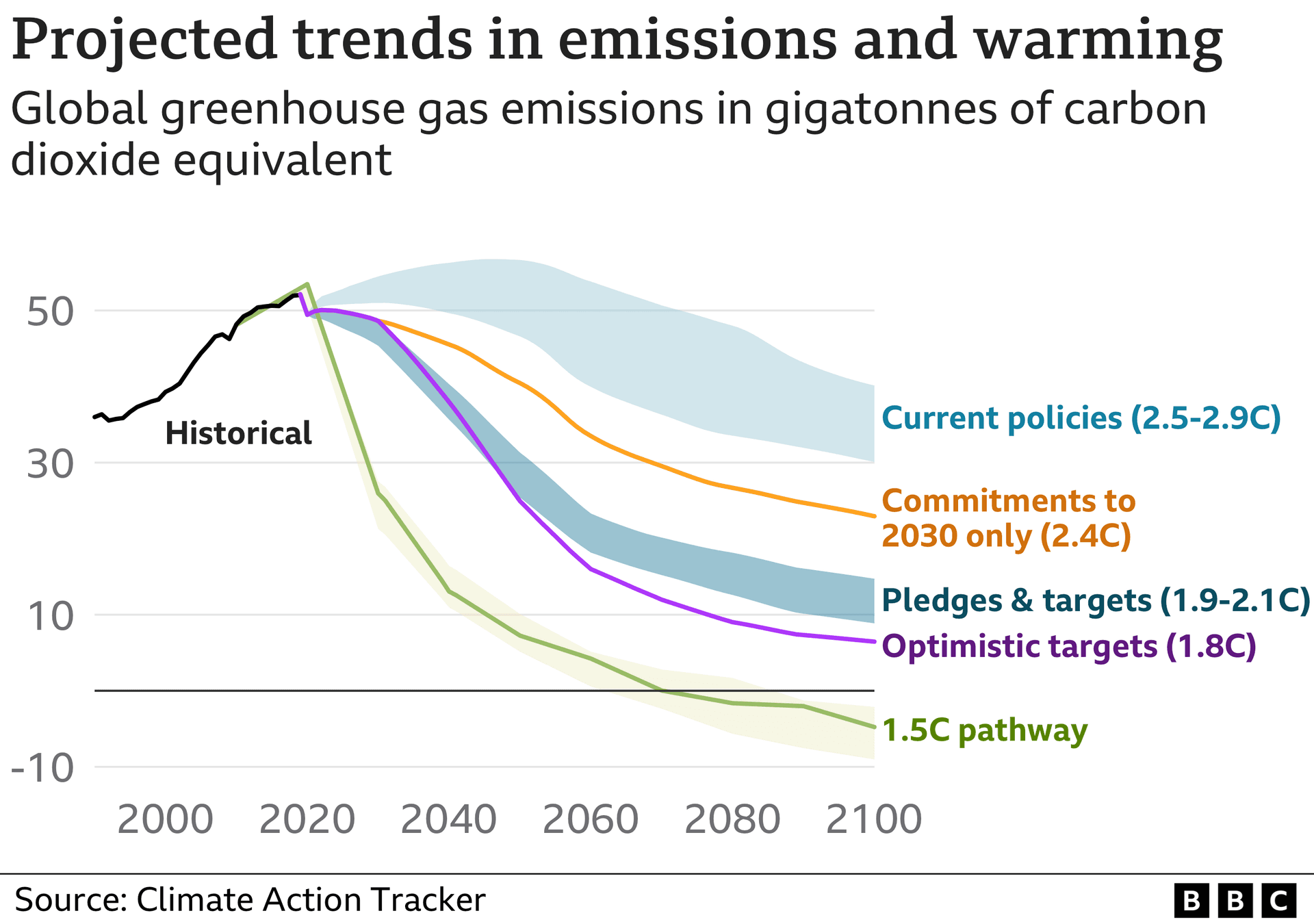

The episode has set off a lively debate among researchers, policymakers and market participants about the vulnerability of long run climate economic forecasts to data and modeling choices. Integrated assessment models and complex econometric overlays are standard tools for translating climate scenarios into economic outcomes. Experts said on Tuesday that such models are necessarily sensitive to specific inputs and assumptions, and that small data mistakes can amplify over multi decade projections.

The retraction highlights two related concerns. The first is reproducibility. Calls for open code, full data disclosure and independent replication have grown louder in recent years. The second is communication of uncertainty. Long run projections are probabilistic by nature and depend on future emissions pathways, technological change, demographic trends and adaptive responses. Critics argue that presenting single point estimates without clear uncertainty ranges or sensitivity analyses can mislead policymakers and the public.

Markets and investors monitor climate risk estimates when pricing assets, assessing sovereign and corporate exposure, and setting insurance reserves. While no single paper determines market outcomes, a widely publicized study that implies severe future economic losses can change risk perceptions and influence capital allocation. With the new correction, some analysts said firms that rely on a small set of high impact studies may need to broaden their scenario analysis and stress testing.

For policymakers the event is a reminder to treat individual academic results as one input among many. Decisions on carbon pricing, resilience funding and adaptation finance require robust evidence, not headlines alone. The authors' intention to resubmit a corrected version may restore a refined contribution to the literature, but the retraction itself is likely to accelerate calls for higher standards of data curation, peer review and transparency in climate economics.

Ultimately the incident underscores a structural truth about long run economic projections tied to climate. They are useful, but they are uncertain. Better statistical practices, broader sensitivity checks and clearer communication of confidence intervals will be essential if such studies are to continue shaping high stakes policy and investment choices.