Pearl Harbor ceremonies show memory shift as survivors disappear

On the 84th anniversary of the attack, officials reported that none of the remaining Pearl Harbor survivors were able to attend memorial ceremonies in Hawaii, underscoring a turning point in how the nation remembers World War II. With the last veterans now centenarians and travel increasingly impossible, museums, families and digital archives are taking on the primary role of preserving first person testimony for future generations.

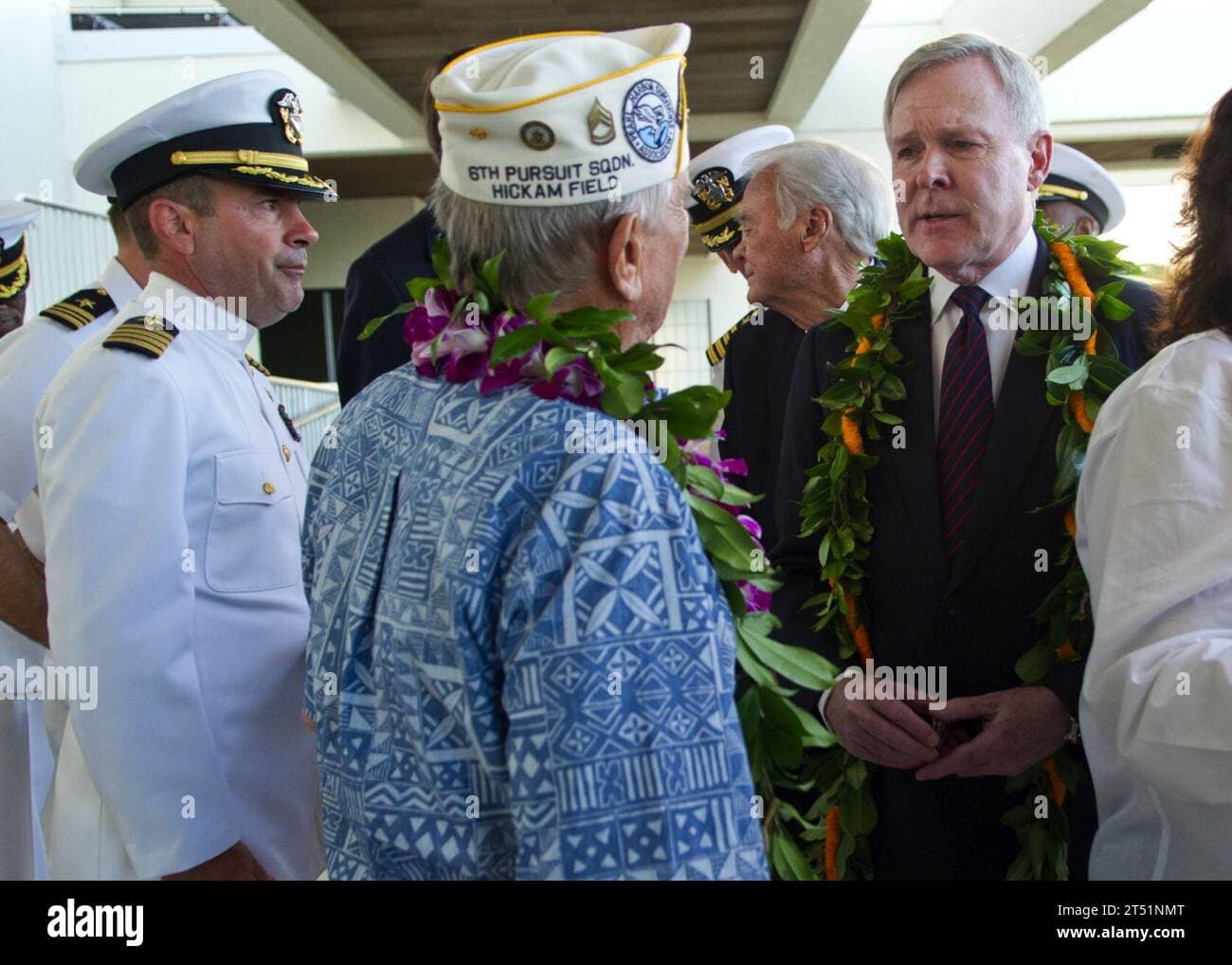

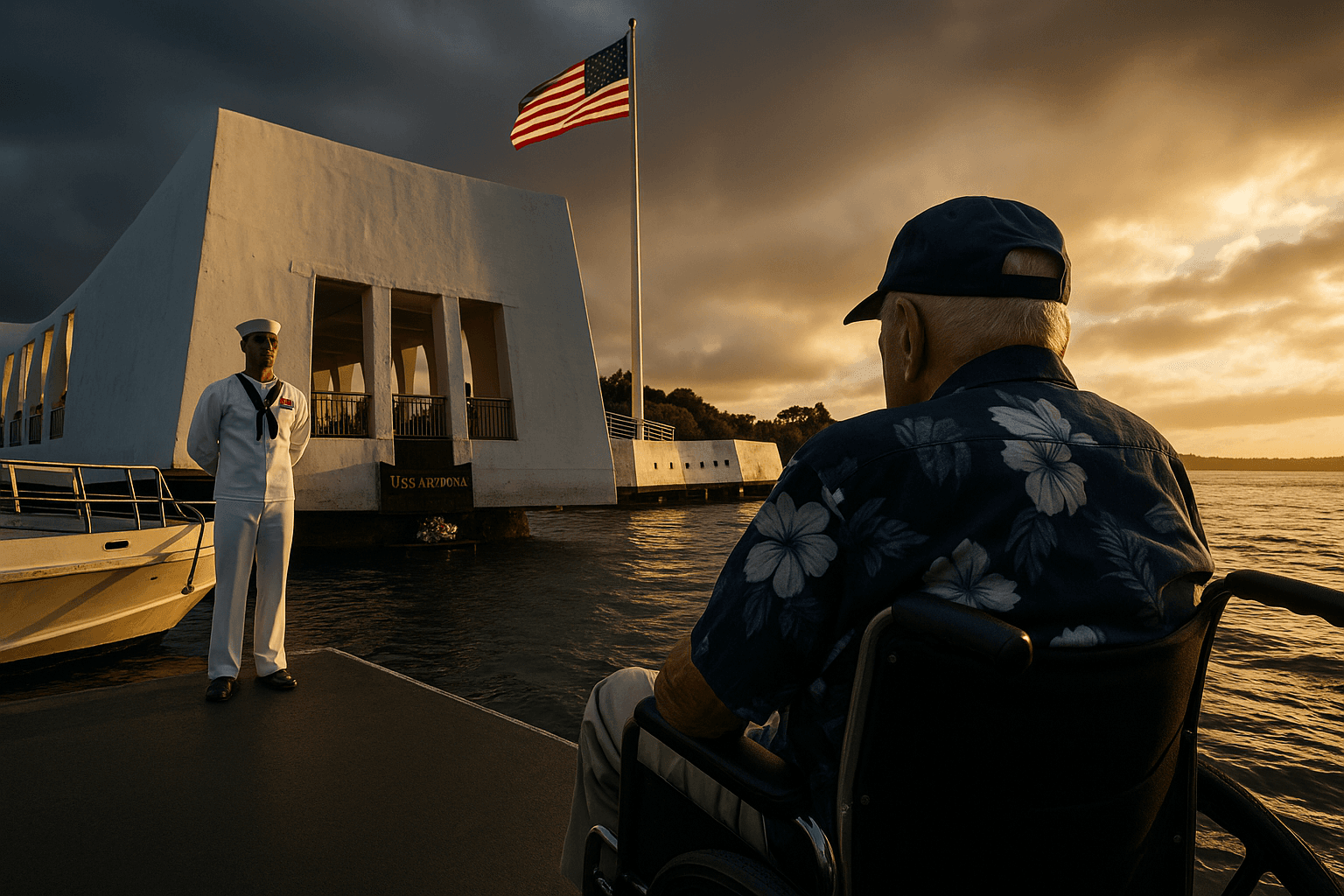

Ceremonies across the nation and at the USS Arizona Memorial in Honolulu mark the 84th anniversary of the December 7 attack, but this year a familiar presence is absent. Officials said that none of the remaining survivors made the pilgrimage to Hawaii, reflecting a sharp decline in living witnesses as the cohort that experienced the bombing ages into its second century. Organizers and historians described the moment as a transition from living memory to mediated memory, with institutions intensifying efforts to preserve testimony through archives, recorded interviews and educational programs.

The absence of survivors is both symbolic and practical. Many of the veterans who were aboard ships in Pearl Harbor or who responded to the attack are now centenarians, and frailty, medical needs and logistical challenges have prevented travel to the island observances. The result is a commemoration that leans more heavily on recorded oral histories, family remembrances, curated exhibits and virtual programming to convey the immediacy of December 7, 1941 to younger audiences who never had a chance to hear these accounts in person.

Museums and public historians are expanding digitization projects to fill the gap. National and local institutions that care for artifacts and testimony are investing in scanned documents, high quality audiovisual preservation and interactive online exhibits intended to keep first person narratives accessible. Family collections and university archives are being called upon to donate or loan material that captures the texture of survivors’ experiences. Educators, meanwhile, are integrating these resources into curriculum to ensure that the event remains part of civic education rather than fading into a distant chapter.

There are also economic and policy implications. The USS Arizona Memorial and related sites are significant draws for Honolulu tourism, and shifts in how commemorations are experienced change the composition of visitors and programs. Public and private funders face decisions about allocating resources between physical conservation of historic sites and digital preservation technologies. Federal and state agencies that fund veterans programs and museum grants will increasingly weigh investments in remote access and educational outreach against traditional maintenance costs for historic properties.

Long term, the passing of survivors compels a reassessment of how societies institutionalize memory. Mediated sources can preserve factual records and emotional testimony, but scholars warn that the loss of living interlocutors changes how narratives are transmitted and contested. Responsibility is shifting toward museums, educators, descendants and archivists to maintain the integrity of those narratives and to place them in broader historical context.

As today’s commemorations proceed without any survivors in attendance, the emphasis is on stewardship. The challenge for policymakers and cultural institutions is to ensure that the raw testimony of those who lived through Pearl Harbor remains vivid and relevant, even as the last direct witnesses disappear from public life.