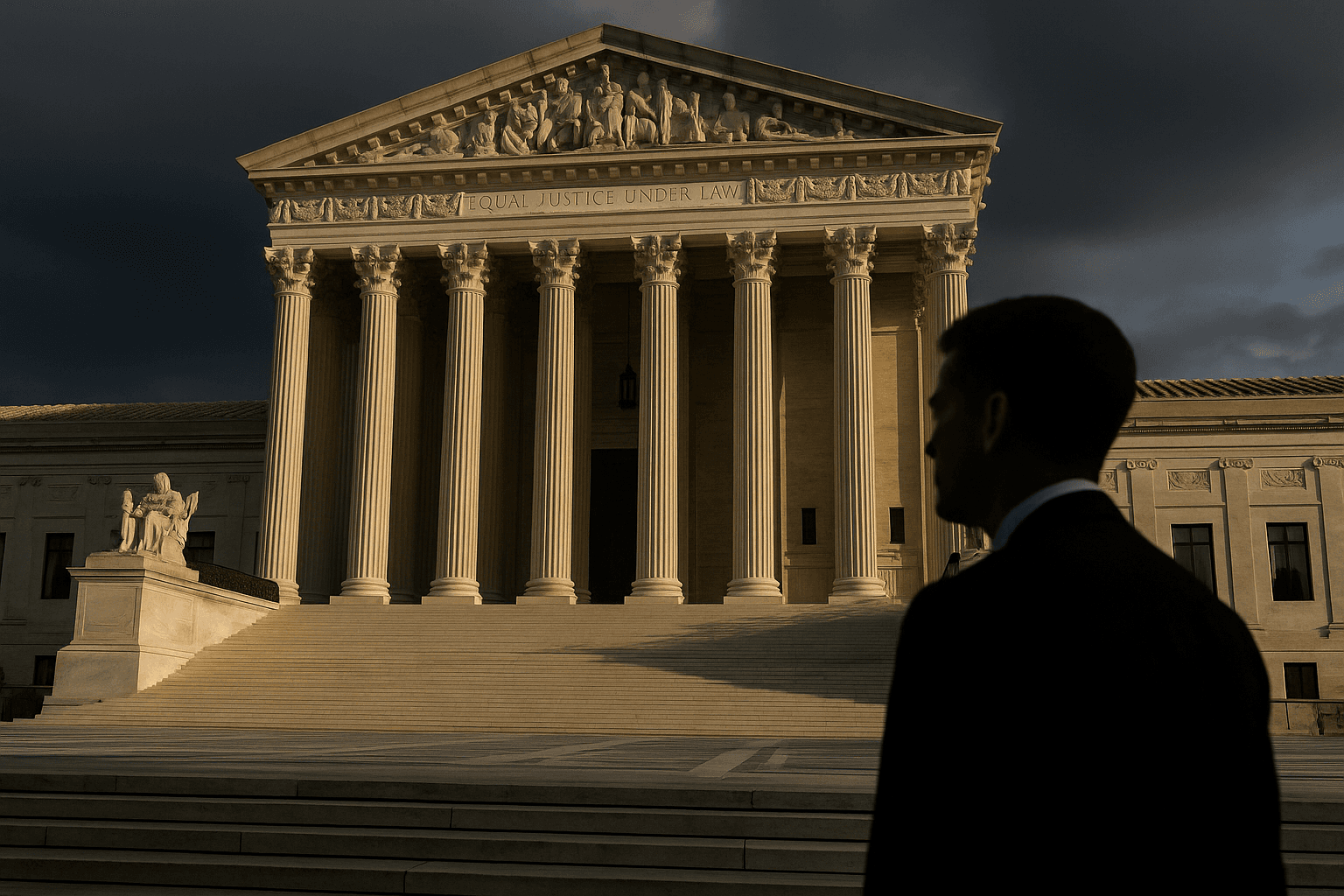

Supreme Court Set to Decide Limits on Presidential Removal Power

The Supreme Court will next week hear a challenge to President Trump’s dismissal of Federal Trade Commission member Rebecca Slaughter, a case that could upend nearly a century of law protecting independent regulators. The decision will shape presidential control over agencies, influence regulatory stability for businesses and consumers, and test the reach of the unitary executive theory.

The Supreme Court will hear arguments on Monday in the Justice Department’s appeal of a lower court ruling that found President Trump exceeded his authority when he removed Federal Trade Commission member Rebecca Slaughter in March before her term was set to expire. At stake is the future of a 1935 precedent, Humphrey’s Executor v. United States, which has insulated heads of independent agencies from at will presidential removal for 90 years.

The case presents the court, which now has a six to three conservative majority, with a clear opportunity to revisit long standing limits on executive authority. Advocates of the unitary executive theory have long argued that the president must retain the power to direct the entire executive branch, including the authority to fire officials who exercise significant executive power. If the justices accept that view, Congress designed statutory tenure protections for members of agencies such as the FTC would be substantially weakened.

Lawyers for Slaughter contend that Congress enacted cause based removal protections to preserve independence for bodies that exercise quasi legislative and quasi judicial functions, and that those protections comport with Humphrey’s Executor. The Justice Department has argued that the modern Federal Trade Commission indisputably wields executive power, and therefore its members are removable at will. The lower court sided with Slaughter, a decision now before the high court on appeal.

A ruling overturning Humphrey’s Executor would not be limited to the FTC. Legal scholars and agency officials warn that making tenure protected officials removable at the president’s whim could reshape the architecture of federal regulation across multiple agencies. Businesses and consumer advocates have relied on predictable, insulated rule making and enforcement for long term planning. Removing that predictability could alter industry compliance strategies, investment decisions, and consumer protections.

The political and institutional implications extend beyond administrative practice. Congress could respond by rewriting statutes to strengthen independence or by creating new enforcement structures, but such responses would require bipartisan agreement in a polarized environment. The court’s decision will also have electoral and civic resonance, as voters and interest groups weigh the balance between democratic accountability and insulated expertise when shaping expectations for regulatory governance.

Observers note that the justices’ ideological alignment will matter, but the legal arguments will be closely parsed. A narrow ruling that limits the decision to the FTC’s particular structure would leave much of Humphrey’s Executor intact. A broader opinion abandoning the precedent entirely would mark a significant recalibration of separation of powers doctrine and alter the institutional relationship between the presidency and independent federal regulators.

As the nation watches the arguments on Monday, the case underscores a fundamental question about modern governance: whether independence built by Congress into regulatory agencies should continue to insulate key administrative decisions from direct presidential control, or whether the president’s authority over the executive branch should be near absolute. The answer will determine how power is exercised and constrained in Washington for years to come.