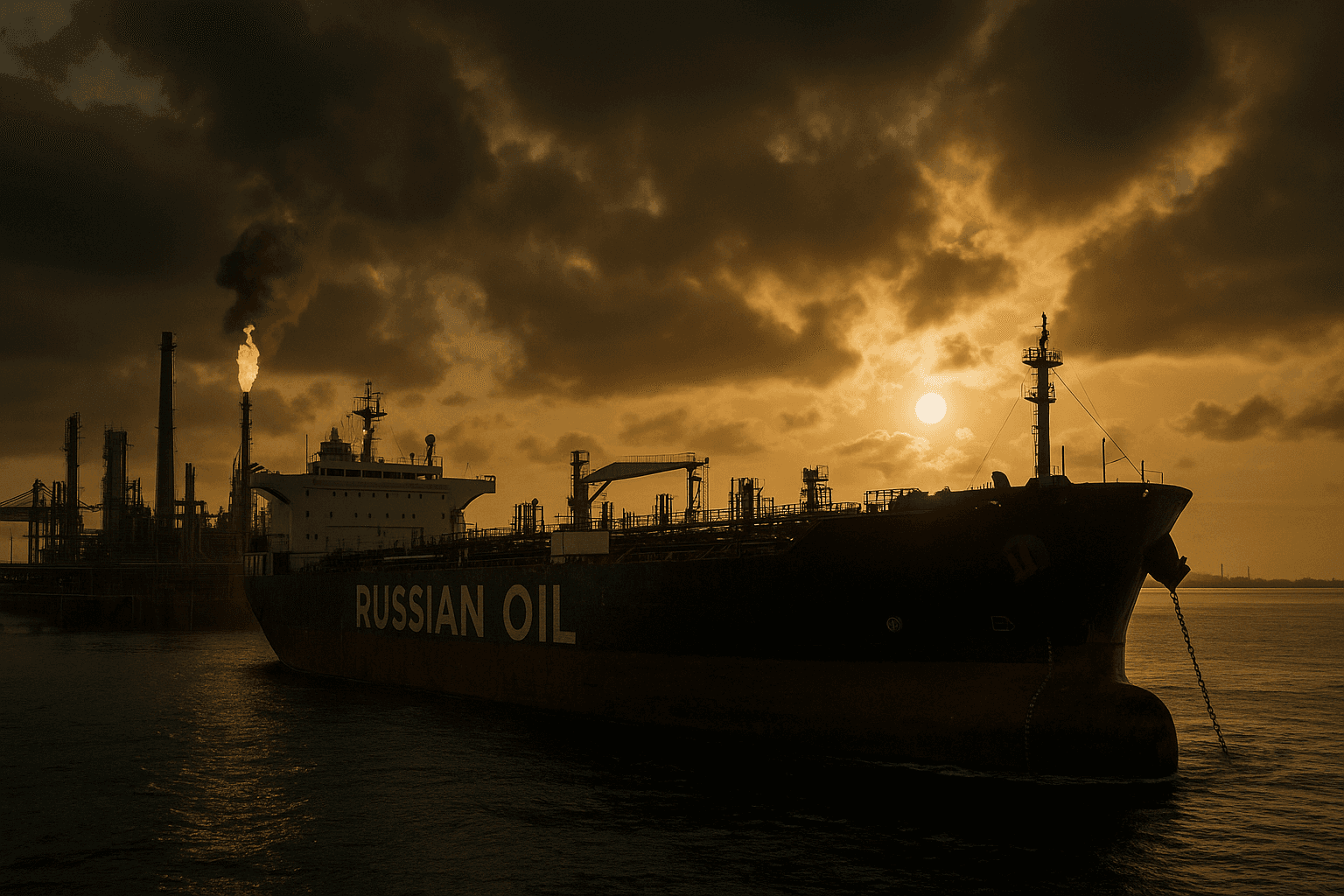

G7 and EU Move to Cut Russian Oil, Propose Maritime Ban

Senior officials from the Group of Seven and the European Union have considered replacing the existing price cap on Russian crude with a ban on maritime services that support seaborne Russian oil exports, a step aimed at further squeezing Kremlin energy revenue. The proposal raises immediate market questions about supply disruptions, higher shipping and insurance costs, and long term shifts in global energy trade patterns that matter for consumers and investors alike.

Officials from the Group of Seven and the European Union weighed a proposal on December 5, 2025 to replace the current price cap on seaborne Russian crude with a broader ban on maritime services for vessels carrying Russian oil unless they meet new constraints. The measures under discussion would deny access to ships, insurance and related maritime services for cargoes that do not comply, tightening the instruments used since the price cap was adopted in late 2022.

The price cap, set at sixty dollars a barrel when it was launched, was designed to limit Moscow’s revenues while allowing continued flows of energy to global markets. The move to restrict maritime services represents a more aggressive enforcement approach intended to raise the economic cost for buyers and shippers that continue to handle Russian crude. Negotiators and industry stakeholders were reported to be studying legal, diplomatic and operational implications as they weighed the change.

Market participants said the proposal would require close coordination with the global shipping and insurance sectors, where compliance is enforced through documentation, access to European ports and the ability to secure insurance cover. Insurers and protection and indemnity clubs play a central role in underwriting risks for tankers and cargoes, and exclusion from these services can materially complicate voyages and transactions.

Analysts caution that implementation would not be straightforward. Potential workarounds include increased use of ship to ship transfers on the high seas, reflagging vessels under non cooperating states, and reliance on non Western insurers or private arrangements that sit outside the jurisdictions enforcing the ban. Each workaround would raise costs and risk, and could complicate tracking of cargo flows, but they also illustrate the friction points that negotiators must address if they move ahead.

From a market perspective, denial of maritime services could tighten the available pool of compliant shipping capacity and push up freight rates and insurance premiums. That in turn would likely increase the landed cost of crude for refiners that continue to source Russian grades. Global benchmark prices for crude often respond more to perceived tightening than to actual supply disruptions, so volatility could rise even if crude availability remains broadly intact.

The policy calculus reaches beyond immediate price effects. A ban designed to more sharply curtail Moscow’s hydrocarbon receipts aims to reduce financing for the war in Ukraine. At the same time it risks accelerating long term trends toward the regionalization of energy trade, with Russia deepening shipping and insurance relationships with non Western partners, and buyers diversifying supplies from the Middle East and elsewhere.

Implementing such a ban would require sustained diplomatic effort among G7 members, EU states and allies in Asia and Africa to limit loopholes and preserve market stability. Enforcement will hinge on the ability of authorities to cut off critical maritime services in practice, and on the willingness of market participants to accept the higher compliance costs that would follow.