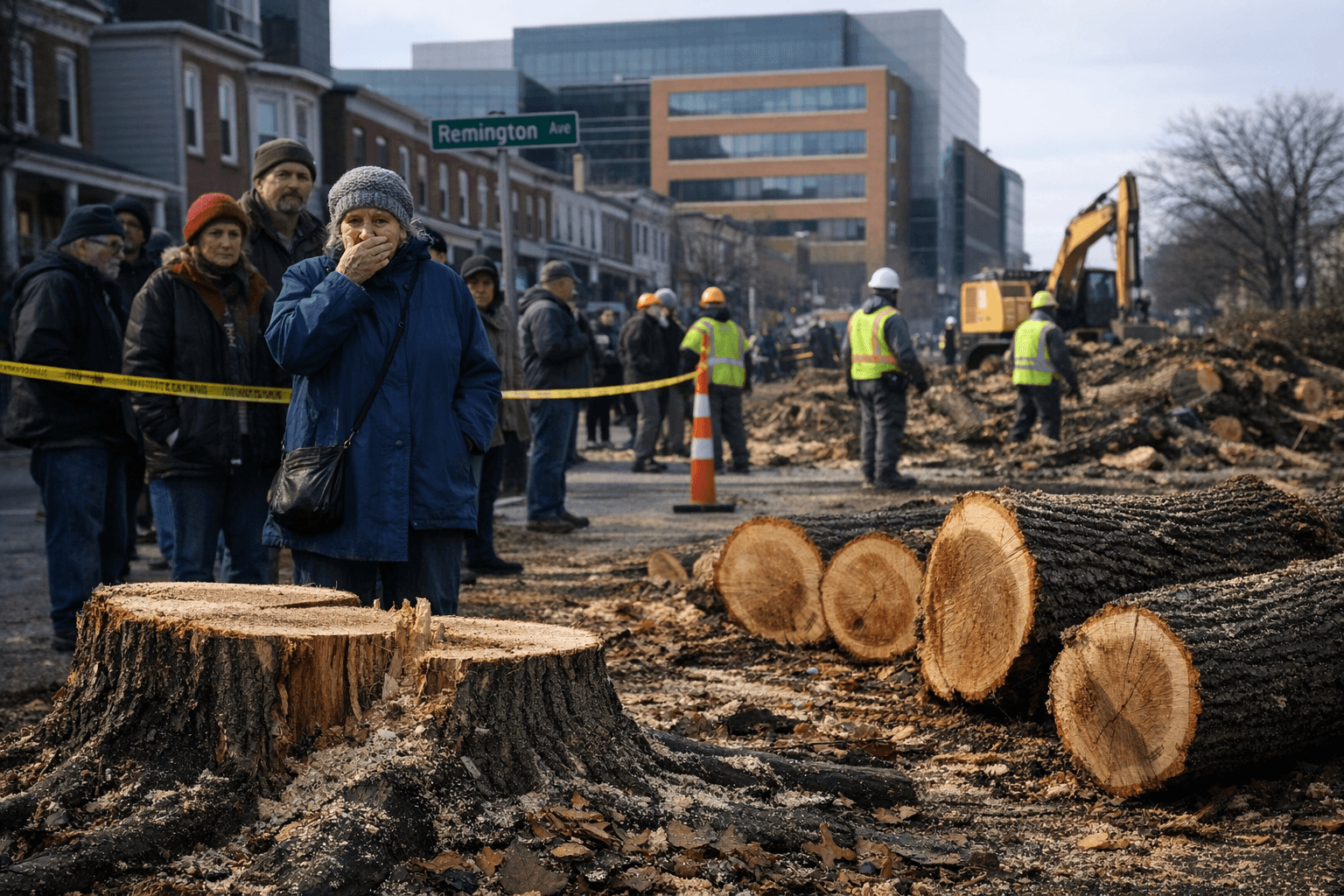

Hopkins Cuts Remington Trees, Sparking Community Outcry and Concern

Johns Hopkins University cut down nine city-owned Northern Red Oaks on Remington Avenue on Jan. 9 for its Data Science and AI Institute project, despite protests, a petition with more than 2,000 signatures, and a cease-and-desist letter. The removals have deepened local distrust of university expansion, raised questions about transparency and legal authority, and prompted calls for enforceable commitments to replace canopy and mitigate impacts.

On Jan. 9 crews felled nine mature, city-owned Northern Red Oaks along Remington Avenue to make way for stormwater and infrastructure work tied to Johns Hopkins University’s Data Science and AI Institute. The trees, many more than 50 years old, were removed in full view of visibly emotional neighbors who had spent months protesting, reciting poetry and gathering more than 2,000 petition signatures opposing the action.

The Community Law Center, representing neighborhood opposition group SPAW (Sacred Parks and Waterways), sent a last-minute cease-and-desist letter arguing Hopkins had not shown it had legal authority to remove trees in the public right-of-way and requested documents the university had not provided. The letter warned of potential legal action if the removals continued. Despite that demand, chainsaws and bucket trucks took down small limbs and trunks, and wood chippers processed the trees while residents reported tense encounters with security personnel and described the scene as having a “surveillance state” atmosphere.

University officials say the removals were necessary for stormwater improvements and infrastructure tied to the DSAI project, and they point to promises of canopy restoration and other mitigation. Neighbors and advocates counter that general promises are insufficient without an enforceable memorandum of understanding or specific, legally binding commitments detailing what will be replanted, where, and on what timetable. The dispute highlights long-running tension between Hopkins and surrounding communities over expansion, transparency and the degree to which institutional plans affect public spaces.

Beyond neighborhood attachment to the oaks, the cuttings carry public health and environmental consequences. Mature trees provide shade that lowers urban heat, soak up stormwater runoff that can overwhelm aging infrastructure, and improve air quality and mental well-being. Loss of canopy disproportionately affects lower-income and historically disinvested neighborhoods, compounding existing equity concerns about who bears the brunt of development impacts.

City residents and local policymakers now face practical choices about oversight and mitigation. Community leaders are calling for clear, enforceable agreements for canopy replacement, transparent disclosure of permits and engineering assessments, and stronger public notice when large employers undertake work in the public right-of-way. For neighbors already wary of institutional power and its neighborhood effects, the removals are more than a dispute over trees; they are a test of whether promises from major institutions will translate into durable protections and benefits for the people who live next door.

Sources:

Know something we missed? Have a correction or additional information?

Submit a Tip