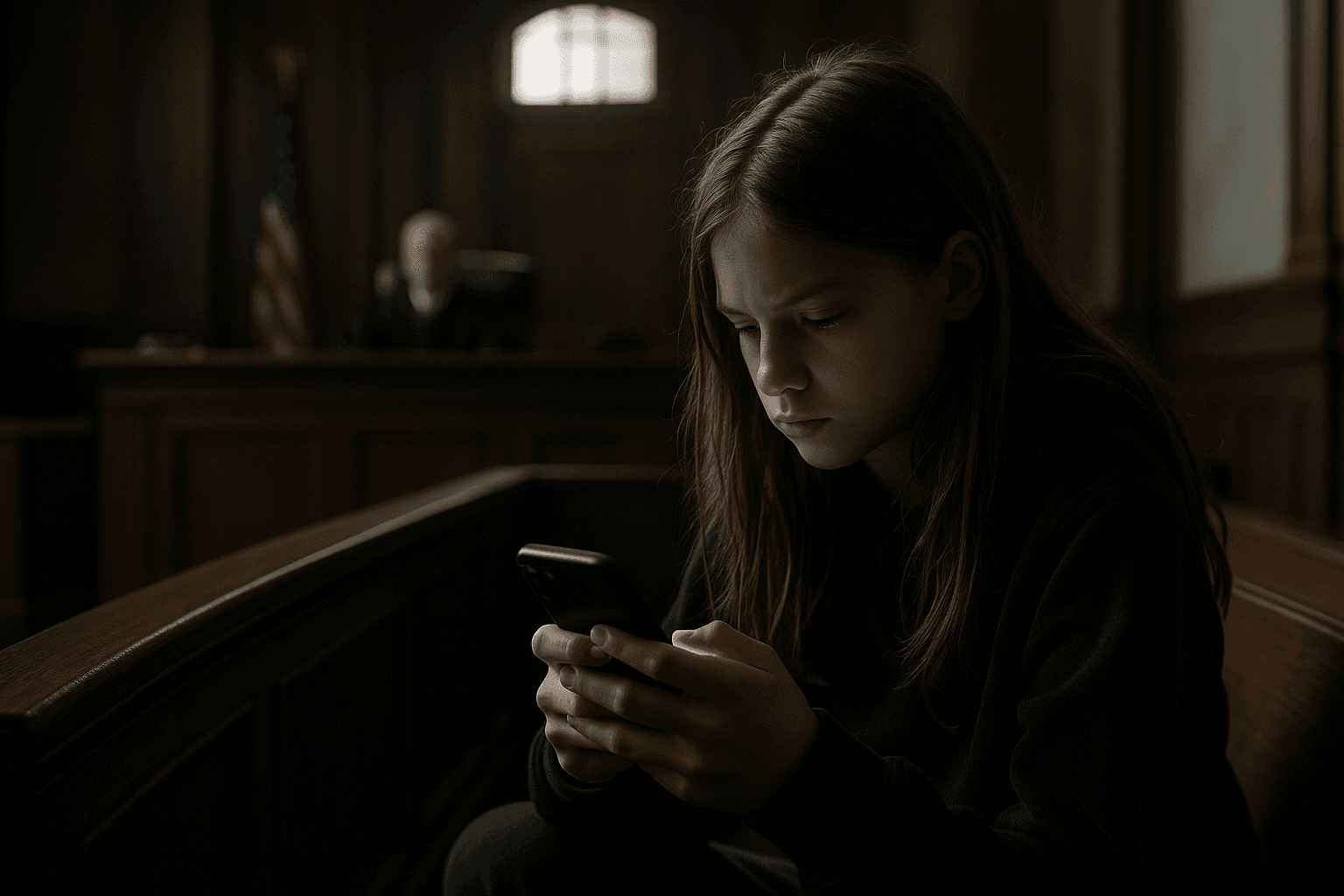

Massachusetts court weighs claim that Meta designed apps to addict children

Massachusetts’ highest court heard arguments on December 7 in a lawsuit alleging Meta engineered Facebook and Instagram to be addictive for minors, a case that could reshape product design and legal exposure for major platforms. The outcome will matter to parents, advertisers, and investors because it speaks to whether states can regulate design choices that drive user engagement and ad revenue.

Massachusetts’ Supreme Judicial Court on December 7 heard a consequential challenge to the design of modern social media, as state lawyers argued that Meta Platforms built features such as endless scroll and persistent notifications to hook children and harm their mental health. The case, brought by the state Attorney General, rests on internal research the state insists shows a link between product design and worsening outcomes for some teens, and seeks to hold the company accountable for the effects of engagement engineering.

State attorneys framed the suit as a public interest action aimed at protecting minors from addictive product mechanics that amplify time spent on the services. They pointed to internal analyses and documents already disclosed in earlier litigation and regulatory probes to argue that the company was aware of the risks its features posed to adolescents. The AG’s filing asks the court to permit remedies that would constrain how certain product elements are deployed to underage users.

Meta responded that the lawsuit, if allowed to proceed, would improperly police editorial and product judgments protected by the First Amendment. The company argued that decisions about ranking, notifications, and presentation are part of editorial discretion and that civil courts are not a suitable vehicle for regulating complex software design choices. That defense frames the dispute as constitutional as well as regulatory, and could limit the scope of state liability even if the factual allegations are substantiated.

The hearing comes as an intensifying wave of legal pressure at both state and federal levels has focused on youth safety and platform design. Lawmakers and regulators have pursued a mix of legislative and enforcement options, from proposals that would restrict algorithmic amplification of certain content to federal inquiries into whether platforms adequately protect minors. The Massachusetts case therefore has implications beyond one state because it tests whether consumer protection or public nuisance doctrines can reach product architecture rather than only marketing or disclosure practices.

Economic stakes are substantial. Meta’s business model is built on engagement, which directly influences advertising revenue and the lifetime value of younger cohorts who begin using platforms in adolescence. Any court-ordered changes to product features could reduce time on site or change the user experience in ways that lower advertising effectiveness and valuation multiples for the company and its supply chain, including ad tech firms and publishers that rely on platform traffic. For investors, the case is another source of regulatory uncertainty that can affect forecasts for user growth and monetization.

Longer term, the litigation signals a potential shift in how democracies hold technology firms accountable for social externalities. If courts permit liability for design choices that target vulnerable populations, firms may face higher compliance costs, redesigned product road maps, and more prescriptive regulation. If the First Amendment defense succeeds, policy debates will likely migrate to legislatures and regulators seeking clearer statutory authority. Either outcome will shape the incentives that govern how platforms balance engagement, safety, and profitability for years to come.